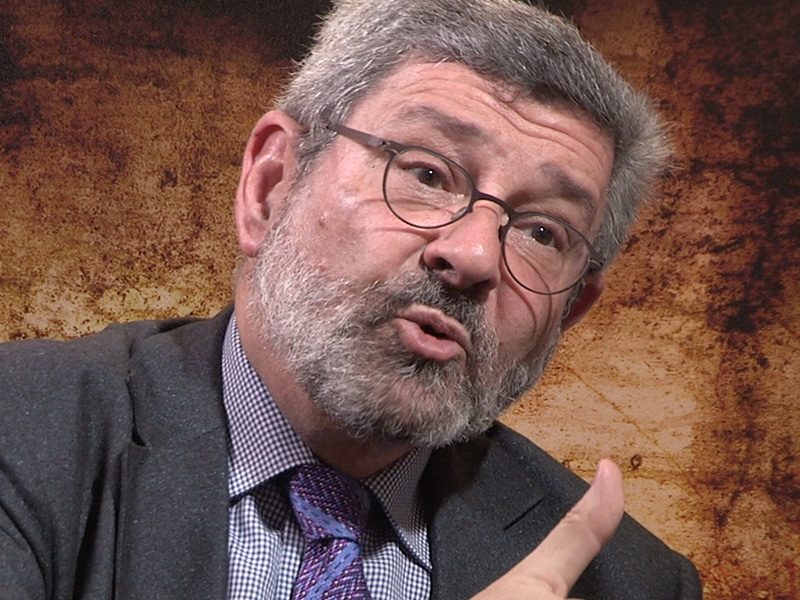

Joan Culla i Clarà

Interviewed May 22, 2018 for Catalunya Barcelona docuseries.

Yes. I’m Joan B. Culla. I’ve taught contemporary history in the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona since the year 1977. That’s 41 years now. I’ve published over a dozen books about Catalan, Spanish and World contemporary history. I’ve written over 1500 opinion pieces in newspapers: “Avui”, “El País”, “Ara”, etc. And, well, I’ve imparted thousands of lessons and had around 8000 students, both in the school of journalism and the school of history, of humanities. Now, we’re going to start with some questions about Franco. Could you tell us about his early life? Franco is the son of a navy military who abandons his family when his children are still young. He is then raised without a father figure which, taking into account that the father’s behavior in sexual matters, in customs matters was far from the catholic ideals in the late XIX century Spain, which was always traumatic for Franco. He felt as if it was something that he had to hide. Actually, his father will die when he’s Spain’s dictator, in the early 40s I think. The circumstances of that death will make Francoist censorship leave the issue untouched. He died in a brothel, a whorehouse. Which shows the great difference in character, in personality and in values between father and son, right? Well, Franco follows the family tradition of pursuing a career in the military. Not in the navy, which at the time is a very aristocratic force, very elitist, but rather in the army, specifically in infantry. He has an average, even discreet career until he’s stationed in northern Africa, in the Spanish protectorate in northern Morocco. There, he has a chance to develop an active military career. I mean, most Spanish officers of the time, stationed in mainland Spain, had mostly bureaucratic careers. They didn’t have any chance to take part of any war, of any fighting, right? That was very important, because an officer that took part of a military campaign had a chance to easily acquire honors and promotions. But, if you were stationed in an office in any of Spain’s main cities -Burgos, Bilbao, Seville- you could only be promoted by service time, which was a very slow process. In order to get promoted just one rank could easily take 15 years. However, in the campaigns in north Africa it was quick and Franco was maybe the most prominent example of these lightning fast promotions thanks to what was called campaign feats, war feats. There’s a discussion about whether he was actually really brave, if he had… It feels more like he had really cold blood. Not so much courage to throw himself all out against the enemy, but rather cold blood. I mean, a remarkable calmness when it came to stand upright in a trench while the moors’ bullets flew around him. And that was really valued by his charges, right? They thought… well, anyway. He has a very, very fast military career in northern Africa, to the point where he is… the biographies that were published during Francoism called him “The youngest general in Europe” I’m not sure if he was really the youngest one in Europe, Europe had plenty of armies. But in any case, one of the youngest, right? Well, the campaigns in Norther Africa are, happily for Spain, over after many great difficulties, in 1926. He soon comes back to Spain and gets a prestigious station, showing that he was someone really, let’s say, with a good record and in the good grace of the military and political leaders. He’s made director, in 1928, of the military academy in Zaragoza. This is a brand new institution, because up until that point, in the Spanish army there were different academies for every branch: that is, infantry, cavalry, artillery, engineers. There wasn’t an institution where the officers from every branch would go. This is a novelty created by Primo de Rivera in 1928. Franco is made the first director of that academy, where they teach a series of courses common to officers of all branches. After two years in Zaragoza, they will leave towards the academies specific for cavalry, artillery, etc. Well, it then seems that his career is looking great when the republic arrives. Being a deeply conservative, catholic, right-wing man, he receives the republican regime in 1931 without much sympathy, rather with some hostility. This hostility increases when, after a few months, the republic decides to terminate the Zaragoza academy to go back to the older system, with each branch in its own academy. The Republic’s first minister of war, Manuel Azaña -the most important leftist politician in Spain at the time- thinks that the academy needs to be closed because it’s politicizing officers even further, and is giving them a common force sense, a transversal solidarity that Azaña finds dangerous. He prefers that artillery goes its own way, infantry another and cavalry another. At the time, Franco has no choice but to accept. Not only is he dismissed, but the institution is closed down. Of course he perceives this as a very grave affront, which will bring definitive hostility towards the republic. The republic stations him in different areas. He’s the military commander in the Balearic Islands in the 1933, I think. He’s careful enough not to become explicitly involved with any of the plots, in any of the military conspiracies that take place from the 31 to the 36 against the republic. I mean, many officers feeling affronted, wounded by the republic, conspire. Actually, in 1932 there’s a first coup that fails. A coup by extreme right military officers that fails, right? He stays out of it. Very careful, very prudent. He doesn’t want to risk his career on a gamble that may not succeed, right? This extreme care will show until the very end, until the conspiration of 1936. Earlier, in 1934, a right-wing government in Madrid considers him again a trust-worthy officer. He is, for a time, in 1934-1935, the Commander-in-Chief. That is, he’s not a secretary of state, since those are civilians at the time, but he is at the top of the military hierarchy. He acts hard from his position against a worker insurrection in Asturias in October 1934. Well, it’s clear that he feels identified with the right wing, and that he dislikes the republican system as well. Well, due to al of this, his professional prestige, when a coup begins to be prepared in the Spring of 1936 -but this time a proper coup, a serious one- the conspirators quickly think of him as key to its success. Mainly for one reason. It’s considered that, for a coup to be successful, it’s necessary that the African army takes part of it. That is, the Spanish troops stationed in the protectorate of northern Morocco, part of which are mercenary units. The “Legión Extranjera”, which is the Spanish version of the French “Legion étrangère”. And, also, the units of Moroccan mercenaries with Spanish officers, known as the “Regulares”. These are the shock troops of the Spanish army. They are units that, not in that moment, but in the last decade had fought in intense combats against the rebel moors, the rebel natives. Then, it’s thought that these units are key to decide whether a coup will be successful or a failure. If they are in with the coup, it has many more chances to be successful. And it is believed that the conspirators think that Franco has the key to unlock these units. That if Franco is in the coup, these units and their officers, who hold him in great esteem and respect him, will join. But if he isn’t in it, there’s no way to know what will happen. Then, the conspirators start to court Franco, and he leads them on. He doesn’t want to act too fast, doesn’t want to make a wrong move. I mean, he doesn’t want to get involved for the coup to later fail. It’s said that during a trip to Paris in the 20 -it’s said, but there’s not much documental evidence. But it’s said that during a business trip to Paris in the 20s, he saw some of the former generals of the Russian Tsar army working as cab drivers. Exiled from Russia and working as cab drivers or doormen in restaurants. That had a huge impact on him, and thought, that can’t happen to me. I can’t afford to make a mistake and forces me to exile and live the rest of my life in misery. Then, it was quite tough to convince him. But in the end they managed it, right? In that moment, the Spring of 1936, Franco was stationed as military commander of the Canary Islands. The republican government wrongly thought that the best way to keep Franco from taking part in a coup was to keep him away from Madrid. And the furthest part they could send him was the Canary Islands. It was a mistake, since keeping him far meant it was harder to control him. I mean, down there in the Canary Islands, he had a lot freer rein without the vigilance that he would have had in Madrid, Zaragoza or Barcelona. But, that was the idea, the further the better. A mistake. Well. Since Franco’s initial role was to rise up the African Army, they needed a safe transport to get Franco from the Canary Islands to Morocco. The conspirators, in a time where there were no regular plane trips -anyhow, he would have had to justify his trip if he had used a conventional transport- decide to rent a small plane. English. It flies from London to the Canary Islands. There, it secretly picks up Franco and takes him to northern Africa. Near Tetuan, I think it takes him. That’s Friday 17thof July 1936. There, with Franco present, begins the revolt. Then, he… Back then, nobody thought yet that he would be the “Caudillo”, the “Generalísimo”, the leader of the revolt. Nobody thinks that, nobody expects it. Not even himself, I’d say. But anyway, his key role to activate the coup is acknowledged. You just mentioned that early on, it wasn’t expected that Franco would become the leader. Could you tell us how that changed during the coup and civil war? Well, that’s a very interesting topic, right? Let’s see, at first… The oldest figure, the greater in age, in curriculum, among the conspirators was a general named Sanjurjo, who had been the leader of a former antirepublican revolt in the Summer of 1932, which had failed. He had been arrested, tried and sentenced to a very long prison time. But after a couple of years, he had been amnestied and he exiled himself to Lisboa. He lived there, Sanjurjo lived in Lisbon. During the months when the coup is being prepared, he is the senior, the figure with the most authority to take power once the coup triumphs. Everyone thinks that the one, with whatever title, that’s not important, president of the republic, whatever. But it will be held by Sanjurjo. Well, it just happens that when the coup has almost started, Sanjurjo decides that he can’t stay in Portugal, that he needs to move to Spain to be on the front line of the events. He left through an aerodrome outside Lisbon in a very, very small plane. It is said that with too much baggage. It’s said that Sanjurjo wanted to carry all the full-dress uniforms, all the badges and all his sabers. Everything. Anyhow, the load of the tiny plane was too much and during liftoff, the plane crashed and both Sanjurjo and the pilot -the only occupants- died. Then, the one that was planned to take power after the success of the coup is out of game. This is the first… instance of good luck that Franco will have in many areas. His main rival, the one that was planned to take the place that Franco would later hold, disappears by chance. The war begins. Like I said before, the key military piece, the strongest military force of the rebels is the African army. And everyone regards Franco as the natural leader of the African Army. This grants him an important position among the many generals. He’s able to negotiate, with the help of his brother Nicolás, in order to get some to his side and to neutralize opponents. That way, between July and late September 1936, he will keep plotting, making moves and making sure he looks as the best chief his colleagues can choose… And, indeed, after, I repeat, many maneuvers, the… at the end of September 1936 there’s a gathering of generals somewhere, in an aerodrome in Castile, where they must decide… Back then, nobody is talking of who will be the head of state for life, but rather who will be in charge during the war. An army, specially one that is fighting a civil war, but any army, is a pyramidal organization. Then, hierarchy is very important. In a military organization, it’s key knowing who is in charge. Maybe it is so in all organizations, but specially in a military one. Then, the military officers think that there’s got to be one that is above the rest. And, in the end, they choose Franco. Again, not by chance, but rather as the result of an operation by Franco’s brother, Nicolas, who will later be for many years ambassador in Lisbon. But, in the agreement that these generals, gathered in a Castilian aerodrome, reach, Franco is designed as “Chief of the government of the Spanish state”. This is, exactly, the approved expression. It is then written into a document that a courier takes to Burgos in a bike to get it printed for the next day’s edition of the official newspaper However, somehow, during the courier’s journey, and the document changes. Instead of chief of the government of the Spanish state, it now says chief of the Spanish state. That was, of course, a maneuver. Someone stopped the courier, said, give me the document, we need to edit it, and changed that. Of course, that wasn’t an accidental change, nor an anecdotic one. Franco was made head of state, not of the government. Well, from that moment on he decided that nobody would get him out of that position. Of course, something else could have happened, but he decided to maintain that status. He had even more luck. The ’37, another of the generals that had an important role in the revolt, Emilio Mola, had another plane accident and died. In this case, there’s more discussion about the accident. Anyway, Mola wouldn’t have been a rival. But anyway, he could have cast some shadow on him. He could have, at some moment, played a certain role. He disappeared. So, all the other generals, as war progressed, accepted -some happily, some resigned to it- the idea that Franco was the leader, that he was in charge. And he started, already during the war, developing a cult of personality. I mean, quickly they started editing propaganda, posters, flags, etc. That said, well, the Italian flag and the Duce. The Nazi flag and the Führer. The Spanish flag and the Caudillo. Nazi, Führer, Caudillo. The same, right? I mean, they started to put Franco on the same level as the German and Italian dictators. And he started, even during the war to receive ambassadors in his headquarters in Salamanca, always with as much pomp as a king, etc. Well, since he won the war… I mean, all of this, if he had started to lose battles and so, would have been questioned, and we don’t know how it would have ended. Since he was successful military, when the war ended the 1stof April 39, nobody argued, among his own, that Franco was, well, in charge. That he was… the maximum authority, that he had the legitimacy given by victory, which is when the cult of personality really started to grow, right? Then, there were all kind of… they used all kind of resources to link this idea of Franco, savior of Spain, etc. Which was his way to make his rule legitimate. But this would last until the very end. If someone had asqued the question, in the ’55, ’64 or ’71, why does Franco rule Spain? Nobody has voted for him, right? Then, why does he rule? The answer would be: because he won the war. That was the answer of the regime at all times. I mean, the source of legitimacy of the regime was victory. The source of legitimacy of Franco’s authority was victory. Franco’s regime is difficult to classify, creating the term of authoritarian regime. Could you tell us about it? This that you brought up is a topic that has been debated a lot by historians. There have been plenty of articles and books about it. What we call, the nature of Francoism. There are those who say that Francoism is a fascist dictatorship, like Hitler’s and Mussolini’s. There are those who say, no, it’s an authoritarian regime. Not totalitarian, authoritarian. There are even some, specially during Franco’s life, who say, no, it’s a regime of limited pluralism. Because inside Francoism, there were different political families, not everyone was the same. There were monarchists, Carlines, Falangists. Then, there was a certain pluralism. But limited, right? I, in this topic, always say the same. If the Francoist regime could be defined or described with a single label, it wouldn’t have lasted 40 years. Do you know what I mean? I mean, if the Francoist regime had been just a fascist regime, it would have fallen in 1945, along with the rest. If it had been just a copy of Hitler and Mussolini. It’s true that from the 36 or 39 to the 45, it was a completely, let’s say, “fascistized” regime. It camouflaged, like a chameleon, with fascism. Because back then, fascism was what ruled Europe, and it looked like it had a great future in front of it. Then, during the years of the civil war and the second world war, specially until the 43-44, Francoism was a fascist regime. But it has enough ability to transform, to shed its skin like a snake. Not change its nature, but it’s skin. Since, in the 44 and 45, specially 45, it was evident that fascism was over -not only over, but also it was prosecuted, criminalized- Franco slowly begins a soft change of direction to “unfascistize” his regime. It’s still a dictatorship, of course, that’s evident. But he’s unfascistizing it. Suddenly, the Falange starts to lose importance. The uniforms, the rituals, right? The lifted arm salute… During… From the 36 to the 45, the fascist salute was compulsory in Spain. The ’45 there’s a decree that, without making a fuss, says, the “roman” salute, as they called it, is no longer compulsory. It was compulsory for the military, for state workers, for those who went to the cinema. But, well, not anymore. Franco corners the Falangists and begins to name right-wing catholic ministers. They no longer wear the uniform, but a suit and a tie. Very soon, in ’46-’47, beings in the world this new period that a north-American journalist will dub the cold war. Franco, suddenly, is like, “excuse me, the cold war?” “Ah, so now in Washington, London and Paris you’re all finding out that communism is dangerous? You’re finding that out now?” “Listen here, I found out the year 36. 10 years ago. From the ’36 until now, I’ve wiped out thousands of communists. Then, welcome to the anti-communist club, but I’m the dean of the club.” I’m making a… But that’s the idea. That’s what saves him. Because in Washington, London and Paris, but chiefly Washington, which is the great occidental power from then on, they are like, “Obviously, Franco is an unreliable dictator.” “He’s someone from whom we have images, footage and pictures parading along Hitler as he inspected the Wehrmacht honor guard” “None of us, in the department of State and the White House”, they say, “none of use would even go have coffee with this guy, of course. Let alone for a bbq or a road trip.” “But, but, if we do anything to make Franco fall, who can assure us that in six months, in a year or 36 months there won’t be a communist regime in Madrid?” “Who can assure that to us? During the civil war it almost happened.” “Who can assure us that those savage Spaniards won’t go back and, shortly after we’ve made Franco fall, there won’t be a communist regime in Madrid?” “You know what? It’s better a known Franco than an unknown. It’s better that Spain is in the hands of a jerk of a dictator and anything you want to call him, but of a” “proven anticommunism than take risks.” Then, what will be the police of the United States regarding Franco? I suppose you’d be interested in that. well, at first, it’s a discourteous attitude, without any enthusiasm. In the ’45-’46, when the ONU condemns Franco’s regime, the United States retires his ambassador from Madrid like many other countries. Then, there’s no hurry to go to Madrid to curry Franco’s favor at all. When, the year 49 the NATO is created, Spain is left out. Because, in theory, the NATO is a group of democratic countries. Well, this is relative, right? They do accept Portugal. But, the Portuguese dictatorship wasn’t established with help from Hitler and Mussolini. Franco’s was. In Portugal it was the Portuguese themselves, and well. Franco’s wasn’t, so not in the NATO. But, since the Iberian Peninsula had a great strategic value for the United States during the cold war, the year 53 -the NATO was founded the ’49, so 4 years later- Washington signs some bilateral agreements with Madrid, in which Franco allows for the installment of American military bases -Rota, Zaragoza, Torrejón de Ardoz- in Spain. It permits the building of oil pipelines to supply the planes, radar stations, communication networks, etc. Then, not in the NATO because the Norwegians and the English will be like, “Dude, who’s this you brought here? Can’t you see what a jerk he is?” But, in another way, we still get him in, right? We get them in the occidental defense mechanism, in case one day the soviets decide to invade western Europe. So, the year 59… 59. The agreements were signed the ’53. So, 6 years later, obviously with no hurry, president Eisenhower decides to comply with the many petitions from Madrid. Ever since the agreements had been signed, Franco had been asking, “Couldn’t the president of the United States make a stop in Spain? I would love to meet him and take a picture with him and all.” The White House, well, you know. In the end, the ’59, when his term is almost over, Eisenhower is like, “well, fine, let’s go.” During an European tour he stops in Madrid, and Franco has the satisfaction of parading down the Castellana promenade, atop an open Rolls, at Eisenhower’s side. In that moment -I’m guessing here, making it up- Franco must have been thinking, “Well, in the 40 I paraded beside Hitler and now, 19 years later, beside Eisenhower. And they call me stupid.” Do you know what I mean? The thing is that Franco had the good luck that the cold war happened. Otherwise, Franco wouldn’t have made it much further than the ’46 or ’47. But fear to communism, fear to instability, etc., made occident, and the americans first, say, “Well, let’s leave him there and get as much as we can from him, get all the benefit we can from him.” Can you tell us about the Alt Llobregat incident? Well, incident, us historians call it the Alt Llobregat revolt, yes. Well, let’s keep it short. This is in 1932. In that moment, in Catalonia… Well, not in that moment. From the 1910s, the worker movement in Catalonia was under the complete anarchist control. Here Marxism had had very little success, and the common ideologic option for organized workers was the libertarian option, right? Which had taken the form of the CNT, “Confederación Nacional de Trabajo”, the great libertarian syndicate. Inside this syndicate, there had always been two different currents: anarchist and syndicalist. The radical and the moderate. With the arrival of the second republic in 1931, this internal tension gets worse. After some fight to control some committees, etc, the radical sector, the anarchist current, controls the syndicate. This sector considers that they shouldn’t let the republic, the republican regime to have time to grow strong. That the fall of the monarchy and the establishment of the republic has weakened the Spanish state. Because now there are in power some republicans that have no governing experience. That they need to use that, the insecurity, the weakness of the republican officials to quickly assault and destroy the regime. The political regime and capitalism and private property and everything. So, in the early ’32, the CNT begins an insurrectional tactic that the anarchists themselves call “revolutionary training”. What does that mean? It means that, no, we know in the first attempt, the second or the third we will achieve success. It’s like training, you need to bulk up the organization and the workers. To train them little by little in the fight against the army and the police. To get them used to repression so that they grow stronger. Just like one that goes to the gym and spends hours there lifting to develop his muscles, right? The revolt of Alt Llobregat is the first and foremost of these “revolutionary training” exercises. It’s an area of Catalonia, not even an official one. An area of 4 or 5 towns, characterized by the existence of mines, which means that there’s a working class that isn’t common in Catalonia. In Catalonia, the most common workers are those from textile factories. There, however, they were coal or potash miners. Who are, all around the world, tough workers, right? Very tough workers, very… Well, they used dynamite as a working tool, etc. Well, taking advantadge of this and with some reinforcements from Barcelona, early in a morning of the ’32 winter, the anarchists take hold of power in these few towns. That means, occupying the city halls and taking control of the “Guardia Civil” posts. They manage to get hold of some weapons, even. They proclaim libertarian communism. They say that money is abolished, there’s no money anymore. That private property is abolished, and all that. And then, of course, after a few hours begin to arrive from Barcelona or Manresa or so, columns of “Guardia Civil”, closely followed by columns of soldiers, to crush the revolt. The fights last for a few hours and they end, obviously, with the defeat of the rebels. It was all something very… well, very basic. And then, well, there’s some dead, hundreds of detained workers. But, in the logic of those who foment these acts, that’s a good result. Why? Becauser repression… Their theory is that repression is the best school for revolutionaries. A worker without much learning, not very aware, if he is beaten up and tortured and then sent to some far away jail, see how revolutionary he is when he comes out. That’s the idea. It’s kind of the same idea that later the Marxists will use in Vietnam, etc. when talking about starting the action-repression-action spiral. Well, the anarchists don’t develop the theory so much, but it’s the same rough idea. Well, that’s that. There were later some disseminated similar events through all Spain in the years 32 and 33, but none of those was successful. Something that we’ve been told in an interview is that simultaneously with the mining revolt in Asturias, in Catalonia there were some… Can you talk about it? In October ’34 there was a great crisis on the whole of the Spanish republic. A crisis with politic origins that was used by part of the leftist workers to attempt, in certain places, a revolutionary movement, a worker revolt. In Catalonia, there was a politic conflict between the Catalan institutions, the Generalitat, and the central government. Because the Generalitat was in the hands of left-wing parties while the republic government was, for almost a year, in the hands of right-wing parties. So, there was an ideological antagonism, that became an institutional conflict. The Catalan parliament passed a law that Madrid considered wasn’t valid and annulled it, which created that conflict. In Catalonia, however, the great worker organization, CNT as I mentioned before, wasn’t at the moment up to begin with any revolts or anything. The idea of the insurrection was more from the socialists and Marxists, who in Catalonia were very scarce. However, they were very powerful in Asturias and a bit less in Viscaya, in the Basque country. Well, when the 4thof October ’34 they announce in Madrid a new government that is even more right winged, the Spanish worker parties, PSOE and communist party, order their members to go for a general revolutionary strike in most of the land, Madrid and so. Here there wasn’t… it had no repercussion. In Madrid and other places, it was quickly stopped, but in Asturias it soon became a true worker uprising, With thousands of armed workers that formed a sort of Red Army, right? They took control of the mining areas of that land, Asturias, And then went to assault the capital Oviedo, which was left half in ruins because while the workers didn’t have artillery, they had dynamite as their most powerful weapon. That’s why most of the old part of Oviedo was left in ruins. They needed to mobilize the army and bring troops from Africa, the shock troops that I mentioned before, in order to put an end to it after two weeks of intense combats. A true war. Here, however, in front of the formation of this government even further to the right-wing in Madrid, the president of the Generalitat decided to proclaim what he then called the Catalan State of the Spanish Federal Republic. Which wasn’t independence at all, but an attempt to make the republic federal. It was a political gesture. Companys didn’t mean to begin any insurrection nor any armed revolt or any of that. Madrid reacted by ordering the army in Barcelona to suppress the movement. There was some gunfire through the night from the 6thto the 7th, and at 6 in the morning it was all over. Some dead, but not many, just a few. But that had nothing to do with Asturias, right? I mean, it was a crisis too, and it ended with the imprisoning of president Companys and his councilors, the suspension of autonomy, etc. But, compared to Asturias, this was child’s play. Why was the agrarian reform law so problematic? Well, that’s easy. Between the great reforms that the republic, while controlled by the left, tried to get going in 1932, among the 4 or 6 great reforms, was the agrarian reform. It was so controversial because it was met with ferocious resistance by the great landowners, who considered that pillaging. The reform included the expropriation of large states with a compensation. It must be said, then, that it wasn’t a communist law at all. The thing is that the republic had the bad luck of coinciding with a time of world-wide economic recession. And in those conditions, there wasn’t much money available to pay the compensations. Then, the process of expropriation, compensation, and distributing the land among the peasants was very slow. This exasperated the peasants in Andalucia, Extrmadura and so, who had been for centuries waiting for the land to be distributed. And when it seemed that this day was about to arrive, it turned out that there wasn’t enough money and it was so slow, and six months went by, then a year, and two, and three. But, at the same time, the slowness of the process didn’t calm down the landowners, who considered that the very idea of the law was intolerable. Even if it happened to go very slow, very slow but it will get to us someday. Then, this can’t be tolerated. The combination between the impatience of the field hands, who were desperate for the day when they would get a piece of land for themselves and the alarm of the landowners who thought, well, sooner or later they will take our lands, made for a volatile combination. And that’s a fast explanation of the huge problematic of this issue. What were the Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista? Yes, the Councils of National-Syndicalist Offensive, in Spanish “Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista” are a small, tiny, fascist party. This one is fascist in the strictest sense. Created in 1932 if I remember right. That is, during the early republic, first one or two years of the Republic by… two men. One of the, Ramiro Ledesma Ramos, was a… how to say it, a small agitator of field workers in Valladolid, Old Castile -Castile and León as is now known. Catholic, far right wing. From a rural world upset by the agrarian reform. In theory, the reform wasn’t supposed to affect the small landowners, but the idea of “the republicans want to take our lands” when mixed with “the republic chases the church”, was a volatile mixture in that environment. Then, Onésimo Redondo… Did I say that name? I don’t recall. Onésimo Redondo is this one, that later Francoism dubbed “Castile’s Caudillo”, right? He died the ’36, just at the beginning of the war. So, that’s another rival less for Franco, right? Well, then… Onésimo Redondo had created something named “Juntas Castellanas de Actuación Hispánica”. Which is the precedent of the JONS, right? Seated in Valladolid. Something very local and very small, it must be… 80 or 100 members tops. At the same time… Let me repeat, the creator of the “Juntas Castellanas de Actuación Hispánica” is Onésimo Redondo. Then, there’s another character named Ramiro Ledesma Ramos. This one is more intellectual, he’s studied in Germany. He speaks and reads German, because he’s spent the 20s, with a grant or something, a few years studying in a German university. And who has discovered Nazism and fallen in love with it. And, then, in the early 30s, back in Spain already, he witnesses with great indignation the proclamation of the republic, the bourgeoise democracy, and all those things, right? And he ends up converging with the Castilian, Onésimo Redondo, and together turn the “Juntas Castellanas de Actuación Hispánica” in “Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista”, this time based in Madrid. It’s something a bit, a tiny bit bigger. Then, there’s this group. It’s a fascist group, with Nazi roots, right? It has a really small force and publishes a tiny magazine. Concurrently with all this, a much more important character than the previous two -Onésimo Redondo and Ramiro Ledesma- Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera… Why more important? Because he was the son of the one that had been the dictator in Spain from 1923 to 1930, Mr. Miguel Primo de Rivera, general and marquis. When his father dies in 1930, Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera inherits the title of marquis. Then, he’s the only fascist leader in the world who is also an aristocrat. Usually, the fascist leaders -Hitler, Mussolini, etcetera- have been poor. They have literally been hungry. Literally, in their youth, right? And then, well, they’ve reached… Well, I always explain the same. Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera had always eaten every meal in a palace, with a maid with gloves that had served him his meal and hi, with silver cutlery, had eaten all courses and dessert. Then, his life experiences have nothing to do with those of Hitler, Mussolini, the Romanian fascist leader… Codreanu, nothing to do with them. He was something of high standing, with intellectual friends, aristocrats, poets, etc. Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera -again, in parallel with what I said before about the JONS- in October 1933 creates in Madrid another fascist party, Falange Española. After 4 or 6 months, early in the year 34, they consider that it makes no sense for two small fascist parties to exist fighting for the same area, which a very small area. So, here takes place the convergence of Falange and the JONS, which results in “Falange Española y de las JONS”. Which is, starting March or April ’34, the basic fascist party in Spain. It is headed by Jose Antonio…. Onésimo Redondo is a discreet man, right? Rather, let’s say, rustic, uncouth. So, he’s no problem, he isn’t a threat. But Ramiro Ledesma is more complex. He considers himself intellectually above Jose Antonio. He considers Jose Antonio a rich kid from good family, which is true, right? There will be some conflict, which will result in Onésimo Redondo leaving the party with some of his followers the year 35. Then, there’s a moment… this is something very small, a detail for specialists. There’s a moment late in the ’35 and early ’36 when there’s Falange, now “Falange Española y de las JONS”, but there’s also a group of JONSians who consider themselves to be the proper ones. The other ones are wrong, they are the true fascists. Also, Ramiro Ledesma will be murdered early in the civil war, so… This is just a little extra. As I was saying, Franco had a lot of luck. When it came to create, during the war, the one-party… He was a military, not a politician. But when he considered that he would need, that it would be useful to have a party, he found that the three leaders of what had been the small Spanish fascism, two were dead. Ramiro Ledesma and Onésimo Redondo had died in Summer ’36, and the third and most important, Jose Antonio, was in prison in Alicante, and would be executed in November ’36. Then, he was able to take charge of the Spanish fascism without having to take anyone out, because the three important leaders were already dead. And dead by the republic, which was perfect. Sometimes, you read that some members of the right-wing spread the rumor that the republic was a judeo-masonic invention and they were trying to turn Spain into a Bolshevik, atheist country. Can you comment on this? Yes, well, let’s see. First. The association between bolshevism and Judaism isn’t a Spanish idea, it comes from far before. From the Russian revolution, from

1919/20/21, there had been through Europe -Germany, well, all of Europe- the theory that the Bolshevik revolution was done, mainly, by Jews. That the non-Jewish Russians were simply the troop, the poor idiots who risked their lives as cannon fodder but the brains directing Lenin’s brain were all Jews. There were some, but not all of them, not even close. But anyway, this synonymy of Bolshevik and Judaism mean the same… this came here during the 20s from Europe. It’s an idea that the German right, the Polish right… well, most every extreme right in Europe, shared this. Here when the Second Republic is proclaimed, this idea takes new strength. Because it’s no longer a hypothetic danger, or something far away. No, now it’s the Second Republic, the work of Jews and freemasons”. Who, in the… conspiranoic point of view of the right wing, was the same. I mean, according to these theories, to call them something, freemasonry was a Jewish invention. Just that in order to be subtle, to have not only one arm but two, at some point they create freemasonry. But it was all the same. Then, there’s this, the Judeo-Freemason-Marxist conspiracy. There’s plenty of literature, books, pamphlets, press pieces, etc. from the ’31 to the ’36, in Barcelona and Madrid, feeding this theory, the Judeo-Freemason republic. Which had some merit, because there were freemasons here, but not many Jews. But, well, that didn’t matter, right? Conspiracy theories have a special relation with reality, right? I mean, if reality fits, great, if it doesn’t, it’s okay. Then, that’s just how it was. In Barcelona, there was between the ’31 and ’36, a printing house specialized in printing books and pamphlets around this theory. It was called “Ediciones Antisectarias”. Because freemasonry was called in these circles The Sect. So, by Anti-Sectarian they mean Anti-Masonic. Well, then, all this… of Course… Why did freemasonry and Jews and all these wanted this, tried to move Spain from the monarchy to the republic? Well, because it’s a first step in a process that will end with a Bolshevik Spain, in the establishment in Spain of a model like the one in Russia, where churches have been destroyed and devastated, where all preists have been killed, etc. so there’s atheism as the official doctrine. That was… the ghost, right? It was the paranoia. Well, of course… Actually, that idea is one of the great sources of legitimacy of the ’36 coup. The generals that lead it, Franco among them, share with this idea, to give it a name. This vision. We need to revolt because if we don’t do it now, soon it will be late. The freemasons, the Jews and all these will have turned Spain into a new Russia and we won’t be able to do anything bout it. It will happen to us like happened to the White Army, who had to run away. They had to go to exile because if they stayed there, they would have been killed, right? I mean, before that happens we need to act. We need to be, in that sense, more effective than… than the Russian, than the conservative Russian class. By the time they wanted to react, it was late already. Not us. We need to do it before and stop this thing. Yes, yes, that… Of course, during Francoism, in the 40s, 50s and 60s this idea will weaken, but will never disappear. In his last discourse, under two months before his death, in October 1975, Franco, from a balcony in the “Palacio de Oriente”, still talks about this famed conspiracy. He doesn’t mention Jewish, because… well, because maybe the Americans would have said something, right? But… I can’t remember the exact expression now, it’s the… Marxist something conspiracy. Well, anyway, the idea of the conspiracy was a classic concept of Francoism, that stays alive in the dictator’s lips until the last public speech he gives in his life, as well as in the regime’s rhetoric. What was Durruti’s role during the uprising and why did he become such an icon? Let’s see. … In Jackson’s book, the author says that the anti-clerical fury was greater in Barcelona than in Madrid. Could you tell us about this? Let’s see, this is a very old phenomenon in Catalonia. I mean, in Barcelona, the first burning of convents and the first great mass killing of firars during the contemporary era takes place in 1835. That is, over a century before the civil war. After many years, in 1909, there happened something known as the tragic week. Which was another explosion of anticlerical violence, specially against buildings. Not so much against people, but there burned 50-60 convents, churches, etc. Then, in the… in urban, worker culture, the church is seen as the worst of enemies. It would take very long to analyze why, but in the list of enemies, in front of the bourgeoise, in front of the capital, in front of judges, in front of the army, in front of the “Guardia Civil”; there was the church. Then, every time the people felt like they ruled the streets, every time that the people had the feeling they could do whatever they wanted, the first idea was to go burn convents and churches. This happens three times in a century, so it’s a tendency. The year 36, this happens in a revolutionary context. In a city where, from the 20thor 21stof July on, there are tens of thousands of weapons in the hands of whoever wanted one. So, this has a great violent part. Not only the destruction of churches, hundreds of churches, religious symbols, images, etc. but also the killing of thousands of members of the clergy. But, like I said, this isn’t a novelty of the ’36 revolution. A hundred years before, the same had happened. Then, it’s something very old, ancient. Surely it can be explained, because the catholic church in Spain had keep an attitude of alliance with the powerful, the grand landowners, power. Then, this had earned it a deep hatred from the lower classes. That is, is was a deeper hatred than they felt for other enemies. And this, every time that… Of course, there’s also that, well, assaulting a barrack is always a bit more dangerous than assaulting a convent or a church. Generally, they aren’t defended, aren’t armed, so it isn’t a very heroic target, it doesn’t need any great… well. Where did all this come from? Oh, right, Jackson’s quote. Well, yes, of course. This is something that north-American historians, for 60 years, have been very curious about, and I understand it. Because this has never happened in their culture, let’s say, right? There’s a north-American historian who must be long dead, Joan Connelly Ullman, who wrote… Wrote a book that was for a long time the reference book about the tragic week. And Gabriel Jackson, among others, studied the anticlericalism of the republican and civil war years. No, the thing about Madrid and Barcelona. Let’s see. Yes, there’s a reason. ’36 anticlericalism violence was stronger here than in Madrid for an obvious reason. Here, for weeks, maybe 3 or 4 months, the armed anarchists were able to do what they wanted without any enemy military threat. The front, all fronts, were very far from Barcelona. Hundreds of miles from Barcelona. Not in Madrid. In Madrid, from the Summer ’36, Franco’s troops started to creep on the capital, and early in November almost had it circled. Of course, the existence of an enemy at the doorstep makes people think, well, maybe instead of burning the neighborhood’s church we could go see if we can stop the fascists, right? Maybe it would be more urgent. We’ll burn the church later, there will be time. Do you know what I mean? But here, there wasn’t this urgency, there wasn’t a military threat. I think that’s why. How were formed the militias that would later go to the fronts In the most chaotic and improvised way you can imagine. I mean, the moment when, like I was saying, when the military revolt is defeated, anyone who is like, “comrade, a rifle”, gets a rifle and some ammo. There’s part of the workers that decide that it’s their thing, fighting fascism wherever it is, right? There are others that say, he, I’m going back to the factory, I have a family and so. But it’s a spontaneous division, hard to put in scientific terms. It depends on personal attitudes, familiar bonds, the way on goes about. Well, then, it’s all done very improvised. On top of all, since the main worker force in Barcelona is the CNT, which was a libertarian, anarchist organization, their culture was completely against all idea of hierarchy. Of some ruling and others obeying. They found it repulsive. Culturally repulsive. Then, that’s, the year 36, everyone who said, I want to go to the front! It’s great. Men and women. During the first time, men and women. Of course, comrade, anything. So, these people went there with all sort of confiscated vehicles: trucks, buses, cars, trains. And they left for the Aragon front as if they were going for a BBQ in the suburbs. Literally, I mean, you see some pictures and footage, see someone with a canteen, and you think, well, that’s the cautious one Because most of them, no, most of them… What happens when we’re thirsty? I don’t know, we’ll see. It was the most improvised… They went, since it was summer, they wore flip flops. Do you know what I mean? Some trousers and a shirt, that’s it. When these militias found the reality, and reality was that there was an army on the other side, that was, well, a disaster, a stampede. Many started, shit, I’m gonna get killed here, better go back to Barcelona. They had to pull out most women, because obviously that had turned… anyway. And, specially, that idea of no, nobody rules here. If we need to decide something, we’ll hold an assembly. Listen, this is incompatible with any war worth that word. Then, that was, slowly, not suddenly, all this initial amateur enthusiasm, this idea that we’re all equal and there are no uniforms and no ranks, had to be left aside because it was impossible to get anything good done like that. Actually, if the militias that came from Barcelona had been a bit more… well, a bit more disciplined and had combat experience, etc, probably they would have been able to conquer during the first weeks the three capital cities, Huesca, Zaragoza and Teruel, right? They were close. But as soon as the Francoists got a bit organized, there was just too much difference, the asymmetry between both sides was too big. Can you tell us a bit about the rents crisis in Barcelona from ’36 to ’37? It’s not a topic I know specially well, let me tell you that. Let’s see. The rent crisis happened because, for a long time, the building of new housing was almost paralyzed in Catalonia. The ’29 crisis had completely stopped it. Then, during the republic years, almost no new houses were built. The great majority of the people -not only workers, but also the middle class, and…- lived in a rented place. The idea of owning a house wasn’t… The only ones who owned it, owned the whole building. For example, a building in the Eixample, and they lived in the main floor. But most people, even doctors and lawyers, lived renting. Well, specially in worker’s housing, the lack of offer, the population growing always at least some, the lack of new offer made the prices begin to rise and that brought protests and… demonstrations. Well, some conflict. What policy did the revolution enact, so to speak? Well, I think that more than a planned policy, it was more of a new reality taking place. Many owners of buildings, of many buildings, were either murdered or in hiding. Then, in many cases it’s just that there wasn’t a landowner to come get the rent. Then, the tenant thinks, well, for now I’m not paying. You know? There were some measures taken, which I can’t explain now because I could be wrong, but I think that that’s what happened for the most part. Just like in many companies the owner had disappeared, so they had to collectivize a bit out of need, something similar happened in rented flats. In many cases. That is, the complete or temporary disappearance of the owners, eased people into thinking, well, this is great, we don’t need to pay a rent. But, after the war there were some issues, because some owners, who came back, said, hey, these guys owe me three years’ worth of rent. When we ask people about life under Franco’s regime, they talk about a grey city. Could you help explain how it could be a grey city for those who link it with sun.? I think that the grey was literal, but, above all, metaphorical. I mean, the many people who talk about the grey Barcelona in the 40s and part of the 50s talk about the atmosphere, for the most part. For example, there’s a text I’m working on now of a… a Francoist Catalan leader from ’59 who says, the difference between Barcelona and Madrid, in that regard, is huge. While in Madrid there’s a certain happiness to live, here in Barcelona, there’s grey and sadness and all. Well, let’s see. We need to take many things into account. One, purchasing power, salaries. If we take as a basis the one they had in the first semester of ’36 before the war, purchasing doesn’t recover until after almost 20 years. Until the late 50s. Right? Purchasing power, not the currency, pesetas. Purchasing power, if it’s at 100 the ’36 spring, it doesn’t go back to 100 until the 57 or 58. then, it must be said, most people didn’t have much money. And that always increased the greyness, because if you don’t have much mone, you can’t go havea coffee. You will think twice before you go to the theater or the movies or buying anything. Then there was, how can I say it? The censorship of the dictatorship brought, on the media, a very remarkable uniformity. That is,, there wasn’t… You went to the newspaper stand and all newspapers said the same. Why? Because they didn’t have a choice, right? So there wasn’t any diversity. Also, newspapers paper was scarce in the 40s and so. So, on top of all, they didn’t have many pages. Magazines, the few that existed, were the same. Very little paper, of course without color. Then, in that sense, this was also that grey. The uniformity in the media. Censorship affected everything. Shows too, of course. The Paral·lel, which had been for decades the Barcelonese Montmartre, now, the erotic, so to speak, shows, with ladies showing flesh, were rigorously controlled and censored. And there was a state worker in the backstage with a measuring tape going about like, this cleavage should be a couple inches higher, and this skirt a foot longer. You know? Well, this didn’t help make things better either. Etcetera. I mean, there was a host of factors, the availability of money, the economic status… Remember, food rationing lasts until 1952. Okay? And power restrictions until ’56. Then, that idea of displays lighted up day and night… there wasn’t power to keep the houses lighted day and night. At night, I remember, I lived the power restrictions as a kid. From 10 pm until six or seven in the morning next day, there was no power. My father shaved by candlelight, know what I mean? Then, I think these are elements that perfectly explain this idea. This will begin to change in the 60s, when the wallets begin to get filled with money, when, well, restrictions are lifted, rationing is over, well, there’s a certain consumism. A certain abundancy. There’s a bust of Francesc Cambó on via Laietana…. I woudn’t say that he gave support to Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship like that. I think it should be explained in more detail, for a longer time, but we don’t have the time. Let’s say that he didn’t oppose the dictatorship. Give it support, he was shrewd enough not to support it. See how shrewd and informed he was that Primo de Rivera’s coup was being prepared the ’23, he organized things so that that day, the 13thof September 1923, he was… He had a ship, a huge yacht. He was with some friends visiting some ruins in Turkey, right? Well, disconnected from the world. There weren’t cells or anything. So, he was able to say, when someone brought it up, he said, no, I found out about Primo de Rivera’s coup a week later. When we reached the first somewhat important city and saw some foreign press, we said, excuse me, what does it say here? In Turkish, what does it say? Nothing, there’s been a coup in Spain. Oh. They, then, no. He was too deft so that you can say he supported Primo de Rivera. He didn’t oppose it, and after a certain moment he began to criticize it. He didn’t do anything, mind you. Franco’s coup, no. Cambó didn’t support the coup. When the coup in Catalonia failed and gave place to the revolution and the murder of bourgeoise and priests and the burning of churches, etc. Cambó considered that he had to support Franco so that Franco would end the war and end the threat on the lives of his friends. Not his own, because he was already out of the country, but the lives of his, friends, the possessions of all his circle, etc. Then, he didn’t support the coup, he supported the francoist side during the war, because he considered -I’m not defending it, just explaining it- that it was a matter of survival. I mean, if Franco doesn’t win, we won’t ever be able to go back to Catalonia. Actually, he never went back. Couldn’t or wouldn’t. But the idea was, not for him, he was living grand in Europe and America. I mean, no… No, he didn’t mean himself, he meant those close to him. The people from the Lliga, etc. If Franco doesn’t win, all these people will become exiles, like the White Russians we mentioned before, for all their lives, their sons, their grandsons, will never be able to return. That had to be stopped. So, he moved cash, contacts, influence of all sorts to help Franco’s victory with the idea, and there he was completely wrong, that when Franco won the war thanks to his help, among that of others, he could go visit him and well, say, my General, I’ve helped you a lot. I suppose you will be so grateful now, right? And could ask for political concessions in exchange. He didn’t know Franco at all and was so wrong. Franco, once he felt comfortable in power, forgot all that helped him, Cambó or whoever it was. He utterly forgot them. Now that he was in power and could do all he wanted, he didn’t take demands from anyone. Well, if there was a demand that fit him, yes. And the demands that Cambó indirectly asked for after war, weren’t… Franco never even considered. So, that’s why Cambó ended up in Buenos Aires, bitter, because that gamble of his… let’s help this guy first to save our things and then because he will be so grateful. Well, the math was wrong.

My name is Laia Otero, at this moment, I’m working in a third sector entity that focuses on studying third sector entities, at the communication’s department.

I’m very passionate about communication, I’ve worked at the communication of companies for quite a long time now, and also, I’m very interested in politics, I’ve always stayed informed, above all because of my experience as a journalist, but also because I’m interested in that.

What’s your position on Catalan independence?

Well, my opinion is that Catalonia’s independence is something that I’m quite excited about nowadays, I think it is very interesting, that it is a political moment that I’m very happy to live through.

And actually, I’d like it to become true, even though I don’t see it clearly right now.

Do you see your generation’s view on independence, and Catalanism, as different from that of your parents’ generation? If so, how?

Well, in my case, well, I think it can be generally said too, but in my case, let’s say I have a more enthusiastic view… I think young people are willing to change, to have a social transformation and then, we can agree more with this whole process.

And in the case of earlier generations, my parent’s, they’re a little bit more reticent because I think that, apart from the fact that it is more or less proved that as people grow older, they get to a certain type of conservationism, well, also, my parents they both depend on pensions, they’re retired right now and then, a political change of this kind what provokes in them is insecurity, if they’ll get their pensions or not.

And then, well, let’s say they’re not quite excited about the idea of a change like this.

Let’s say that I think that, in general, people from earlier generations, older people, they’re more ‘pro-establishment’ so to speak, that newer generations want to break with the Spanish State, in this case.

Do you recall any stories that may have been passed down to you describing life under Franco?

Yes… a lot of them.

My parents were both very active politically, let’s say they were in the Francoist resistance in different political movements.

My mother was active in the PORE [Partido Obrero Revolucionario Español], that was one of the Trotskyist branches of the period.

And my father was also connected to libertarian movements in Barcelona.

And well, they’ve told me about political actions they did above all, about how they used to organize meetings… different kinds of meetings, one of them that I think it’s quite funny is, for example, that they decided a place, everyone was pretending, for example, at a train station and everybody was pretending to be on their own and at a certain moment, someone would pick a whistle, made it sound and then, everyone’d run, throw papers with the slogan, with the manifest of the moment and then, they would dedicate themselves to distribute them, to throw them until there would sound another whistle and then, everyone would disperse and go back to where they were.

They’ve also told me how they’ve run many times in front of the police, in front of ‘the grey ones’, as they were called then, in order to escape from the possible repression for participating in protests because it was forbidden the freedom of assembly, the right to demonstration and then, everytime they did a political action, they were afraid of the police arresting them and sending them to prison.

And so, they’ve told me many stories of this kind.

And then, I’d like to share a story I find specially relevant.

And that is that my father used to have quite a curious appearance in that moment, he had a beard, a pretty long hair, he used to wear glasses.

And once, he was walking in his neighborhood, which was Nou Barris back then, and a police car stopped, they took him, got him into the car without giving him any explanation, he didn’t know where they were going, then they stopped at a pharmacy, showed him to the pharmacist and asked him ‘is it him?’ and the pharmacist said ‘no’, and so they left him there and then they went away.

And he stayed there very surprised and deeply scared.

And it was because they were looking for Txiki, an ETA member of the period and I guess they both looked alike.

I mean, it was actually very lucky that the pharmacist didn’t confuse them and tell them it was him because then, they executed [Txiki] by firearm.

Then, I wouldn’t be here if we wouldn’t have been that lucky.

Many people we’ve interviewed have explained that they are, at once, Catalan, and not Spanish, but simultaneously are against independence from Spain. Will you explain this nuance, as it is an important distinction?

I think the reasons may be twofold.

On one hand, it may be that part of the people that claim that have attained a quite high standard of living, that own businesses… and probably, they are connected to the rest of the state and the fact of being at a state inside the European Union is beneficial for them.

And then, I consider that probably, although they feel Catalan, once again, I talk about what we’ve already discussed about earlier generations, and that is the fear of rupture, the fear of what is going to happen when independence is declared, it is a completely unsure scene.

Then, above all, people that have any kind of dependency [on the state], either in my parent’s case, because of a retirement pension or either because of businesses they own.

I understand that the scene of being an independent country is not something they really want because they believe it would be something negative in order to keep their standards of living.

And well, rupture isn’t something they really want.

And on the other hand, I also understand there are people that may think that the creation of a new state is not the answer, right? That creating more borders means… Many times, what is being sold from the pro-independence discourse is that the creation of a new state would mean improvements for society, right?

For example, laws that have been approved in the Parliament but then have been killed in the Spanish state, as an argument in favor of independence.

Then, I understand there are people that believe that… For example, sometimes I’m in that position myself, I don’t have a solid position, I flow a little bit… so, people that think that if a capitalist neo-liberal state inside the European Union is what is going to be created, just as the Spanish state is, then it doesn’t make sense doing it, right?

Let’s say that if that is to be in a state that is the same, then there’s no need to separate.

Do you have recollections from September 20th, the day that Guardia Civil invaded, arrested government officials, and seized pro-independence propaganda from local print shops…?

Well, I wasn’t in the streets that day but I guess that, like many people, I followed it through the media, in my case through radio, many others through television probably.

And I remember it was a tense moment of not knowing what was going on and of asking ourselves why this kind of repression was happening.

Well, not exactly why… because it was clear that it was because there was the will of holding a referendum and the Spanish state didn’t want to allow that.

But I do remember that tension I felt when hearing all that was happening.

I also remember watching videos of the gathering in front of the CUP’s office, they [policemen] wanted to get in to move propaganda away but they couldn’t make it because they didn’t have an order.

And there were people like me, I also thought about going there but well, I was working and finally, I couldn’t go… let’s say that when I could go, it had faded away, right?

But I remember that gathering, I remember how people were quite angry and thinking about what was that, that it wasn’t a rule of law to arrest people for wanting to vote.

And also, [arresting] someone who was at the economy ministry, right? That let’s say that is quite important to an autonomous community, or in this case, to a state.

What is Spain’s Gag Law, and how does it impact journalism?

The Gag Law is a law that was approved by the Popular Party and that, actually, it is an unfortunate censureship law that more than journalism, although it also affects it, what affectates the most is activists.

It is a law which Green Peace protested a lot about because they do many actions in buildings, for example, they climb them and hang a poster in the top of the building…

This kind of actions are punished by the Gag Law.

Also, there was… with the arrival of smartphones and all that, there is a very big movement of whenever someone sees a police assault, they record the police in order to inform on that assault.

With the Gag Law, what it says is that one can receive a fine for recording a policeman and so, you cannot record it to inform on an assault, then we were left out like orphan without our defensive weapon against the state’s violence.

If we had already few weapons because a policeman’s word is always worth more, then with this law we had even less power let’s say.

And then, all the repression that comes from social network that it doesn’t make any sense, that anything like this hasn’t been seen in any European or western country, that is imposing fines or giving people a prison sentence for posting in Twitter, for example.

Or artists for making an artistic representation like the well-known case of ‘the puppeteers’ that was due to this law that they went to trial, they had been sued for making a play with puppets, let’s say, mocking the police, the church, the king… right?

Let’s say, what political humorists have done all their lives.

Well, these people had very serious consequences for expressing artistically.

There have always been cases of musicians, of rappers that have been arrested for the lyrics they’ve written.

Also publications, ‘El Jueves’, which is a satirical magazine, well-known in Spain, it has had to move its magazine away a couple of times, they had to go to trials.

To me, it is simply a sign of how little democratic the current government of the Popular Party in Spain is, the kind of laws they create in order to restrict the freedom of expression and above all, to limit the freedom of expression to all those that they decide.

Because then, there have been complaints for fascist attacks, let’s say, about desiring the death of people that defended certain left-wing things, and there have been no consequences.

Then, not only it is a law that restricts the freedom of expression in general, but it limits the freedom of expression of certain kind of population.

Why are people wearing yellow ribbons now?

Well, the yellow ribbon is a symbol that asks for the freedom of the political prisoners of Catalonia that have been arrested as a result of the process of independence of Catalonia.

Currently, in prison, there are the ‘Jordis’, [Joan] Puigcercós… no, not the Puigcercós, [Oriol] Junqueras is, the Jordis, and then, there is the economy one… how is he called…?

Well, currently, we have political prisoners as a result of the independence process, and let’s say, we have two people that didn’t belong to any political party for easing the voting on the 1st of October, they are the Jordis, they belong to associations, let’s say, popular associations, ANC and Òmnium have been platforms created by civilians.

Then, political parties have joined it and I think even associations, business, City Halls…

But its basis is popular, then, people are very indignant that these people are in prison… also, they have families, they have children… and the thing is they are imprisoned without bail, they don’t even have a bail to… while waiting for the trial, but they have to stay in prison.

And well, when we walk the streets of Barcelona, in this case, we can see many, many people either with yellow ribbons or either wearing yellow scarves too.

And here we can appreciate the people’s expression of indignation.

Did you participate in any manifestations? If so, can you provide an anecdote that, perhaps, puts the viewer of this film right there with you?

I participated in the manifestation of the 2nd of October, after the repression that people suffered for voting, for going to vote.

And the truth is that it was a very impressive protest.

I’m used to going to manifestations and normally, there’s hardly a soul there.

Then, it was very emotional to me going to such a multitudinous protest.

I remember we went to the Jardinets de Gràcia that are, let’s say, in the upper part of the center of Barcelona and we couldn’t move.

We were waiting and waiting weather the protest advanced but it didn’t move at all.

In the end, we snuck among the people and tried to advance and not to stay there because we wanted to walk for a while, and walk with the protest, right?

But… but it’s not that we started walking because the protest started to move, but we started walking along the lateral in order to get to the areas where people were walking already.

And curious anecdotes… well, for example, a very emotional thing that happened is that there was a boy in the protest with a flag of Spain as a kind of cape, let’s say, and he had a poster addressed directly to the president that said ‘Rajoy, I feel Spanish but I’m against violence’, right?

That day… look, I get goosebumps.

That day, people not only went out on a massive scale to ask for the independence, although a lot of shouts of independence could be heard obviously, but they went out to condemn that totally inappropriate repression that old people suffered, that people that was going to vote peacefully suffered and that there was barely no violence on the 1st of October.

I mean, it is true that some images of some vandalized police cars have been seen but as a general rule, it was people with ballots against nightsticks.

Then, it was a very emotional protest, a very multitudinous protest and I have good memories of it.

What was your voting experience on October 1st?

Well, although I live in Barcelona, I’m still registered in Cerdanyola del Vallés, a city that’s just behind the mountain of Collserola, next to Barcelona.

And so, I went there to vote in the polling place I had been assigned.

And I remember that I voted in the morning, then I went back to my parent’s, I had lunch with them and I started receiving all the outburst of news, of images of what was happening in Barcelona and other villages… also, very small towns of Catalonia in which there had been very serious, violent scenes and it was really overwheming to see them.

I remember being very, very worried and thinking ‘I cannot stay at home while they are doing all this to my fellow citizens’.

Then, after lunch, I went to some polling places of Cerdanyola, I did kind of a route because we still were unsure whether the police would show up or not, because there was no criterion for the Civil Guard to appear in a city or an other.

And then, there were many people at all the polling places protecting the place, that is, a human barrier, forming human chains so the police couldn’t get in.

I remember being at a polling place in Cerdanyola and hearing rumors that the police was coming, and so we all formed a line, we took each other’s arms to avoid that they could get in and take the ballot boxes.

Then, the police didn’t come, finally, it was a quiet day in Cerdanyola, no one came but it is true you could feel that tension.

And so, in the polling places that I went to, it is true that everyone was… well, on one hand, happy, excited with the whole process because a lot of people were involved, but on the other hand, a little bit of fear of the possibility that something similar to the images that everyone had seen somehow could happen.

Can you relate any anecdotes about friends’ experiences voting in Barcelona?

Well, yes, the truth is that all my friends participated in it in one way or another.

I have friends who went to the polling places to sleep.

I remember that a friend went to the polling place that is at Travessera de les Corts at night, and they used kind of a code in case there was a secret police there.

And they said ‘tonight, we’ll play three games’, and they divided it into hours, I don’t remember which ones were exactly, but like from 8 to 12, we’ll play pachisi, and that meant that whoever wanted to play pachisi had to go there and so, people that was staying there from 8 to 12, went that way.

From 12 to 5 we’ll play poker, and so, all those who ‘played poker’ went that other way.

And then, from 6 to whenever it was, well, there was an other game… and they had to bring snacks for all those who had stayed to sleep there and all that.

And then, I have two friends that live in Barcelona, one of them lives near Sant Pau’s Hospital, and it’s very close to a polling place, and he told me that he woke up at 6 or 7 in the morning because of the applauses, shouts of ‘we will vote, we will vote’.

And well, he said that well, considering the bad part of people waking you up on a Sunday, that he was very happy because of that excitement that people was having in that moment.

And then I have an other friend that was at Indústria street, near the Sagrada Familia, and well, that he kept moving from one polling place to the other because they were very near to each other, and that because police vans were getting closer.

And he told me he guesses that seeing the amount of people that were there protecting the places, that also being so near to each other, people kept moving from one to the other.

He thinks that they didn’t charge because of that, because police vans had been getting closer but they didn’t actually get out of the vans at no time, luckily, but he does remember the tension of moving from one polling place to the other, and so.

And also, as an anecdote, that he was there, he spent the night at the polling place, and so he was there first thing in the morning, and that he found out that the ballot boxes had arrived because everyone started clapping, but that despite being there, he didn’t see how the ballot boxes arrived there at all.

And it is curious because this proves to what extent they had everything planned and very well prepared.

Many Catalans flew to Belgium during the first week in December. Why?

Well, they flew to Belgium because one of the most important things that a state that wants to be independent needs is international recognition.

And after the declaration of independence, we got almost no recognition, from any country.

Then, on one hand, it was a show of force and a show… well, a request to Brussels, precisely, because there is the EU’s headquarters, and so it was to ask for that international recognition to the EU states above all, which are states that are near us.

And also a show of supporting the current president of the Generalitat, that is Carles Puigdemont, who went to Brussels due to the judicial hunt he’s suffering in the Spanish state, and so, avoiding being arrested as other politicians have.

Will you talk about the reactions of the European political community since the referendum crisis began?

Well, the truth is that reactions have been very conservative, supporting the Spanish state and its president a lot, Mariano Rajoy.

We got almost no recognition at all.

It is true that some secretaries from some countries, they’ve asked for… well, that it be a debate, it has been debated at the Parliament of Flanders if I am not mistaken, which is also an area that has cultural differences with the country it is in.

I’d also say that it was discussed at the Parliament of Scotland, which is also an area with hopes… some people that live there have the hope of becoming their own state.

Then, let’s say the most positive reactions we received were from those places that can empathize with the Catalan situation.

But the rest of the European states… it is true that some of them condemned the violence that voters suffered on the 1st of October but none of them made a challenging declaration towards the Spanish government, but rather, on the contrary, they have been supporting declarations.

Will you discuss your experience on election day December 21st?

It was a quiet and regular experience, I guess because as these elections were organized by the Spanish state, they didn’t send policemen to repress people and so, there was no problem at all.

Well, a part from that, I followed the counting very interested after the voting.

I found remarkable the level of participation, which went up to 80%, which is a lot.

Normally, there is not that much participation, it was a subject that people were interested in, actually.

And it had been showned, let’s say, through the people that received more votes, parties that didn’t take a stance as En Comú Podem, that decided that its discourse was ‘nor independence, nor 155’, which is the article the Spanish state has applied in Catalonia, the economic intervention of the autonomous community.

Then, they condemned both roads.

And this party, for example, had an important descent regarding votes.

The ones that have won in votes are, on one hand, Ciutadans, a quite right-winger party, more right than what I think people believe, and they clearly bet on the union of Spain, so there was no independence, among many other right politics.

What I found very sad is that laborer neighborhoods, working-class neighborhoods, voted for a party that actually, goes against their own interests.

And then, on the other hand, it is true independence won, but no pro-independence party won the elections because they were divided into three parties: ERC, Junt– Sorry, they’ve changed their name many times and now… PDeCat, yes and CUP.

Then, joining these three political forces, they’ve won, they’ve clearly won the elections

But well, the truth is that I found it quite… I was very surprised and I think that everyone was, that PDeCat got so many votes, ERC was expected to be the first pro-independence force instead of PDeCat

And that quite disappointed me, I have to admit, because PDeCat is clearly more right-winger than ERC, and so, it was evidence that this movement doesn’t look after social matters and people are voting for the right more than for the left

CUP, which is the radical leftist party, for example, it also lost votes

Pro Independence parties maintain a parliamentary majority. What do you think will happen next?

Actually, I don’t know, I can speculate but i have no idea what will happen

I think that whoever says he/she knows what’ll happen, is lying because we’re in an entirely unknown scene, and we cannot predict it

But well, my negative part thinks everything will be the same, that repression will work because also, not long ago, PDeCat’s president, Artur Mas, who was the leader of Convergència Democràtica back then, as they used to be called, he started all this independence process, and he said that the independence movement wasn’t strong enough to impose itself

Then, let’s say this movement is quite discouraging to me, and I think that if I had to say something, I’d say we won’t see independence, not in the short run

Backing up a couple of years, will you explain what 15-M was all about, and what your personal experiences were in the context of that movement?

Well, 15-M was a popular movement that rose up by surprise a little bit, I think it surprised everyone, but it was a very beautiful movement, in my opinion

In this case, it was a really leftist movement that was asking for a social agenda inside the political agenda, that what wanted…