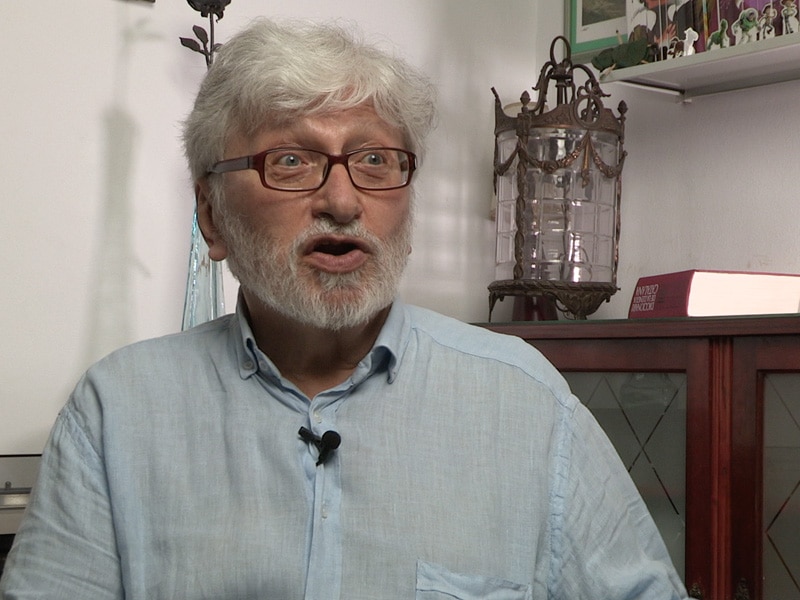

Jordi Peñarroja

Interviewed July 8, 2017 for Catalunya Barcelona docuseries.

My name is Jordi Peñarroja.

I was born 17th January, 1944.

Right now, I make books.

I’ve worked in cinema, doing industrial documentaries. I’ve also been a photographer, focused on documentary photography.

I’ve also taught photography. Later on, I’ve written and taken pictures.

The exhibition of 1888 was presented as the great success on one hand, as as Barcelona’s great transformation. But not everyone agreed.

For instance, Almirall didn’t agree at all. Why didn’t they agree? Because of the Spanish use that was made from the government of Madrid.

This can be seen in the sculptural frieze on top of Barcelona’s Arc de Triomf [Triumphal Arch]. It was the main entrance to the exhibition.

Barcelona is represented through a beautiful and cheerful feminine figure, and, next to it, there’s Mrs. Spanish Castile grabbing her arm, like saying: “You’re mine, and you’re not leaving.”

A lot of people noticed it, and one of them was a young writer named Emili Vilanova.

He wrote a very funny story called “Falòrnies”. It was set in 1950 and it explained the arrival of Castile’s ambassador to Barcelona.

Hence, an independent Catalunya, in 1950. We are running late.

Well, the Febre d’Or is before, during, and after. It’s connected to the exhibition, to the railroad, to the construction fever of railroads.

People thought it was a never-ending business. Obviously, later on, with the demolition of walls, not just Barcelona’s, but the rest too,

It was linked to urban expansion and real estate speculation. This is not new, this comes from…

What changed was that during the exhibition, modernism began. And, of course, if today’s Barcelona has this much at an architecture level, and not only in the Eixample,

it’s because of the exhibition. In addition, building technology changed radically. The great hotel of the exhibition,

located in the Moll de Fusta, it’s a hotel built in 3 months with 1000 rooms. That’s a lot for that time.

Domènech i Montaner. He was the one that built this hotel, and the restaurant of the exhibition, now called Castell dels Tres Dragons.

He’s built other important buildings such as Hospital de Sant Pau, and El Palau de la Música.

Well, with the conditions of the working class of the time: horrible. Misery and company.

The libertarian movement started long ago. That is, for example, you have the Icarians, the ones who go to America. Above all, there’s still an avenue called Avinguda Icària

that goes past where it goes, and has the neighborhood it has around. Back then, they were people who came from Poble Nou. Some of these Icarians [sentence unfinished]. Montoriol himself,

the politician, and inventor, was an Icarian. Then, this evolved, and so there was the need to set up trade unions or mutual aid societies.

All of this, went [sentence unfinished]. And people answered to the repressions. The fact that Barcelona was called La Rosa de Foc, [The rose of fire]

was a reaction caused by the repression. Otherwise, there wouldn’t have been any bombs.

Liceu’s bomb? Liceu’s bomb was an unfortunate joke. Those people didn’t measure the propagandistic

effects that an action could have. Society in general felt disgusted by an action like that. Why? Because it was an outrage.

It wasn’t selective.

Same old history. It fits within the same thinking.

The trials of Montjuïc were trials done with the same guarantees that a trial would have nowadays in the TC.

The Eixample comes from before/is previous to that. The first house is located in Urgell street, corner with Florida Blanca.

It’s that building that was squatted, with the coalmine and such. That was the first building built in the Eixample. We need to think how it was.

The Eixample was basically, wheat fields. The truck garden of San Bertran, that belonged to a chapel, was located in Paral·lel.

But this is what it was: fields. Clot is named after Clot de la mel [Clover honey] because beehives were grown there.

The way from Portal Nou to Clot was full of truck gardens, too.

This can take hours to discuss, and I’m not an expert. But what’s funny is that they want to demolish a building, the Jutjats nous (new courts), built during the fifties – sixties after

having demolished El Palau de Belles Arts from 1888 exhibition. After the exhibition, this building was rented in order to hold different events. There was a huge hall/space that could be rented.

And this room was rented by the anarchists to set up the CNT in 1910.

Socialists’ trade union, the competence.

Solidaritat obrera was a CNT newspaper printed, on the last stage, in a building near here. Consell de cent, corner Villarroel.

It’s a place that belongs to the parish church of Sant Josep Oriol.

The Tragic Week was an outrage orchestrated by the Dirección General de Seguretat. Some simpletons fell for it.

It was a tragedy orchestrated from Madrid in order to weaken Catalanism, and to confront the working class with Catalanism.

Who should we talk about? About El Noi del Sucre, killed by Severiano Martínez Anido and co? Or maybe about Escaso and Durruti, both imported from León? Some people say that they were funded by the DGS.

Who should we talk about? Because at the beginning of the twenties, and at the end of 1918, (when) Catalan representatives proposed the statute of Catalunya to the Parliament of Madrid,

which, by the way, was knocked over. At the same time, the pistolerisme blanc, beheaded the Catalan leading members of the CNT with wicked intentions,

and paves the way for Primo’s de Rivera dictatorship.

The FAI was a group within the CNT, and that journalist, whose name I can’t recall right now, from Manresa, who was killed by the FAI on July 18th or 19th in 1936…

…well, he had had access to information that showed that the members of the FAI were funded by the DGS from Madrid.

Well, the general strike of 1917 has a very obvious cause. The industry makes a fortune thanks to the World War I by selling stuff to France, England, and the Central Powers,

because they were in war, and they lacked everything. The industry here takes the opportunity. Prices rise, but salaries don’t.

And that’s it. Those are the causes. Hunger is what moves people.

Spain was crap. I mean, Spain had just lost the Cuban War of Independence. It didn’t have a navy, its army was out of date. It wasn’t going to get us anywhere.

Best thing they could do was to stay at home, and that’s what they did. Although the king [he uses a pejorative work for king] was in favor of te Central Powers. He just liked to show off. He got along with Wilhem II, the German Emperor.

But yes, I mean, Spain couldn’t make it anywhere. It couldn’t make it anywhere. It would have been knocked over at the first slap.

What was the Rif war?

Oh, the Rif war… a business. It was a war mounted for/by the iron mines located in Rif’s mountains. The inhabitants of Rif,

which weren’t moroccans, they are something else, opposed to it. It took them a lot. In the Rif war, the Spanish army showed, once again, their incompetence. Their superiority in men and cannons was useless.

The Solidarios, the Aguiluchos? Groups of anarchists.

How did he end up being in power? Because Spain was a disaster, and that king [pejorative term], Alfons XIII, Cametes [Thin legs], was a man that loved to show off, and easily brainwashed.

And, in fact, Primo de Rivera agrees with the king to make his famous military uprising.

How did the Second Spanish Republic form?

By accident. No one wanted the Republic. People went to vote for a municipal election, and Republican parties won in the cities. And, with the typical improvisation of the time,

they proclaimed the Republic from the city councils. Madrid had 2 options: to throw the army and the Guàrdia Civil to the street and make a bloodbath,

which would have been a disaster in the long run. The army and the Guàrdia Civil refused. They didn’t want to play this game. The king left, and so the Republic came.

Oh, a Worker’s Republic, how nice! Well, a centralist constitution. A republic that cut down the statute of Catalunya as much as it wanted

when it was discussed. More or less like today.

It took its power in name, just in name. The Second Republic declared itself non-denominational, which isn’t bad at all. But what is not good, is to make an anti-religious politic.

Why? Because you attack people’s believes. It’s necessary to differentiate between church as an institution and religion. The institution can be arguable, but religion touches feelings and believes,

and you need to respect that. The Republic mixed everything. They blew it up.

Alejandro Lerroux was a swine, to put it nicely. He was an agitator paid by the DGS sent to Barcelona. After the Second Republic,

he devoted himself to politics. Moreover, he gave name to Lerrouxism, as an activity, a way of doing against Catalunya’s affirmation.

The Second Republic didn’t give a cause to the Civil War. It was the military who started the Civil War, and it was everything but civil.

Its often said a lot about the Spanish Civil War, when the truth is, it was a war of Spain against Catalunya. The statute of autonomy of Catalunya bothered them, even though it sucked.

POUM was a marxist party. It was accused of being trotskyst, even if it wasn’t. It merged a series of parties.

Some of them were peasant farmers, and belonged to that party deeply-rooted to Lleida. I can’t remember the name. It was a conglomeration. Both Andreu Nin and

Claudín, were a part of it. A series of people. It wasn’t a stalinist party. It didn’t bring together stalinist ideals. In the May Days of 1937, there was a purge,

the party was removed, and Andreu Nin was killed. Besides being a politician, he was an excellent translator from Russian. He had translated Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy…

Oh, ERC… Well, ERC is a party that throughout the second Spanish Republic, it’s everything but pro-independence. It is a party created in order to win, or at least to participate in, the municipal elections of 1931. They won it by surprise.

I mean, they won it by surprise because Macià is the public face. He is a charismatic man famous by the conspiracy of Prats de Molló, and so he wins.

There was another party within ERC named Estat Català. They were pro-independence during the thirties, unlike ERC.

PSUC? Well, the stalinist party, that’s it. You need to keep in mind who was married to Gregorio López Raimundo. And how did he talk, besides writing poorly.

POUM wasn’t as dogmatic as PSUC. I met a peasant farmer named Josep Paner, who appears in Homage to Catalonia by Orwell, with the name of Benjamí.

This man was the head of Orwell’s century in Lenin’s column. I don’t know why they decided to name it this way, but anyway. POUM’ members in Aragó’s front.

This man wasn’t dogmatic, nor stalinist. They were sure about it.

They were left-wing, but non-sectarian, and, moreover, they were people whom you could talk to, unlike the fascists. They didn’t have any problem with the rest of people.

Whereas PSUC was a stalinist party, and that was it.

Oh, how nice… The People’s Olympiad was an attempt failed by the military uprising of Franco and co. An alternative Olympiad to the one celebrated in Berlin in 1936

in honor and glory of nazism. Left-wing people from all over Europe, came together and celebrated the People’s Olympiad in Barcelona.

Orwell, as previously discussed, came to Barcelona as a journalist to cover the event. What happened? Well, that he got excited when he saw the hell of a row.

He joined the milicia because he was a socialist, a member of an English minority Labour party. He wanted to fight the fascists. That was it.

18th of July? A huge mess. In Plaça Catalunya with Telefònica, in the Rambles, in the Drassanes, in a monastery located in Diagonal that meets

Beilén. I think it’s Beilén. There were messes all around the city. The CNT stayed awake all night, and concentrated trucks in order to confiscate stuff (he doesn’t say what they confiscate) and armed people

in front of Júpiter’s Stadium in Poble Nou. The Guàrdia Civil were the ones that ended the day.

The Guàrdia Civil went to its barrack, located in Poble Nou, and went up Laietana. They arrived to Sant Jaume square, they dug they heels in, and they put the roses (not sure at all if he says roses) of Lluis Companys.

They were better shooters than the others, they had a good shot. They ended the day.

With the general Arengonel (not sure). He’s a general of the Guàrdia Civil, unfairly forgotten.

Well, it’s not that Barcelona wasn’t a city divided by social classes. Classes were, and are, there, like in the rest of Catalunya.

Classes, then and now, aren’t very delimited. There’s not a huge difference. The steps are not as marked as in Madrid.

Unlike here, people love to show off. Even the bourgeoisie is more discreet here.

How can someone that lives in the factory, and that has built houses for the workers, be so different?

They might be bourgeois, but they don’t need to show off. The fact that their clothes aren’t as ruined doesn’t mean they don’t work hard.

It’s the cliché: the boss raises and lowers the blind. He’s he first to arrive, and the last to leave. This is serious. This explains

the fact that people looked for the boss in the factory, in the workshop, and in the office. And the man said: don’t touch this one.

And then the property was seized. It was collectivized, but the owner was still the director. This happened. And this

was a way of doing that occurred more in Barcelona than in Terrassa, for example. A lot of business men who enjoyed showing off

were murdered in Terrassa. But not here because society was more… [unfinished sentence] Franco’s supporters had already left.

I know people with a better understanding of this topic. But there were really serious collectivizations. They kept the books perfectly since the beginning.

They were even able to import and renew machinery during the war and the post-war. The owners, once they returned,

found the business modernized. This happened in more than one place.

Difficult, difficult, specially at the beginning. Later on, some anarchists went too far, which made them impopular.

The Control Patrols were disbanded, and the Generalitat regained the control over the law and order, that had been previously lost. But then, May Days of 1937 happened.

The May Days were used as an excuse so the government of the Republic, which established in València, could take the power of the Generalitat

in order to avoid those kinds of riots. Which were, by the way, caused by PSUC.

Well, there were a lot of them. There were a lot of them. The first bombing of Barcelona was naval, not aerial. The Italians bombed the city when it was dark.

They were looking for Elizalde, a factory located in Gràcia that built aircraft engines. The thing is that, they shot from a huge distance, and the bullets and missiles reached the city slowly.

I met a woman who heard the sound of the missiles from her home. The vacuum made by the missile broke the branches that were on its way.

They just broke. But that was a naval bombing. Then the aerial bombings came, and there were all sorts of them. Almost all of them were made by the Italian air force

located in Mallorca. There’s something we need to thank the Spanish Republic for, and is that, in 1936, there was an expedition in order to regain Mallorca made

by the Republic. There were volunteers from the principality and València at Alberto Bayo’s command. They disembarked, and established camp as a link. They were successful.

And, once they start being successful, the government of the Spanish Repiblic withdrew the air coverage and the navy from the war. They were isolated,

and so they had to evacuate, otherwise they would have died. Even so, they are injured. They are massacred by the fascists, and widow nurses murdered.

This appeared a few years ago in a TV3 documentary. Mallorca was the great aircraft carrier used to bomb both the Cap de Creus

and Murcia. We need to thank this bombings to Franco and his Italian allies, and to the government of the Spanish Republic.

My father went… well, went, he was recruited. He was in the battle of the Ebro.

He had a better time than the rest because he wasn’t killed or injured, that’s why I’m here. He was taken as a prisoner when they were retreating. He was sent to a concentration camp in Asturies.

Asturies is cold as ice in January, and so people died both from hunger and from cold. Once they had purged/mopped-up the most significant people who opposed the dictatorship,

the ones that were left were given the chance to enroll the legion. My father enrolled because he was sure that he wouldn’t be sent to the front. Why? Because he was not someone to trust.

He could shot an officer from behind. They were sent to Africa, and he joined up to campaign, which meant that

he would return home once the war was over. This counted as the military service. He would be an ex-combatant knight, and more things. He made good friends, and with good friends I mean gypsies and these kind of people.

This was useful during the Civil War, but it’s another history.

[Durruti] was from León. He liked looking smart. They were vain, but because of the times.

Joan Garcia Oliver was an odd man from el Delta de l’Ebre. He is a very odd character. He has a book of memories because he ended up being a secretary of

the Republic, or a minister of the Generalitat, I can’t remember. He was a very intelligent man. There’s a tale attached to this man, and is that, once, when he was either a minister or a secretary,

he was invited for dinner. Someone told him that he knew how to sport a tuxedo even though he was an anarchist. He replied: “Of course! I was a waiter before the war.” Waiters used to wear tuxedos.

Life under Franco’s reign. Barcelona was a gray city, to begin with. It was the main characteristic of the city. You were on the street, and it was a gray world, the people, everything. Gray flooded the city. The only thing that stood out

were the streetcars: besides being noisy, they were red. They ran like a hare [he actually says “demons”, but I don’t think the expression exists in English] by some streets. And then there was the hunger

People famished. They were poor. What happened, then? Well, people breed rabbits, pigeons and hen in the inside balconies.

People did what they could in order to survive. Then there’s another thing I remember. It’s a childhood memory. I lived in a bar that was my parents’ business.

We lived in the same place. And I was the child of the house and so I ran around. People talked, and there’s a work stuck on my mind

from that time, and it’s the famous crisis. The crisis. People talk a lot about it nowadays: that the crisis is ending, that we are getting out of it. The crisis never ends. We are always living in crisis.

It’s obvious that there’s no progress without crisis.

At a daily level, I mean, let’s see. Police has picked on me for sitting next to a girl in a bench like this. Not like this, no no no, like this. The girl is over there.

And moreover, they told me: “You could, at least, pretend when we walk by.” What am I doing? What do I need to hide? It may be silly,

but it’s something that always happened. There was the feeling of being in an occupied country. My parents, for example,

didn’t have a concrete political affiliation. They had never been bounded/linked to the Catalan movement. They were just locals,

and that’s how they felt. They saw it like something foreign. They didn’t feel occupied, but they felt they were something else.

A lot of people felt this way. Keep in mind that political parties were forbidden back then. Catalan press didn’t exist. I remember how surprised I was

when I was 14, and a man, a doctor, gave me a book written in Catalan previous to the war.

I didn’t know Catalan books existed. I didn’t know it, and I was 14. Catalan, for me, was a language spoken at home.

This is repression. The attempt to erase a country, a culture, a mentality. Language is more important than what people believe,

because they create mental mechanisms. Catalan has a lot of affirmative expressions, whereas Spanish has a lot of negative ones. It’s not the same: “Menos mal” and “Sort que” [thank goodness!]. It’s not the same. It’s another mentality.

It created a different mental mechanism. Like saying the time. Catalan time is similar to the English one. When you say “un quart de dues”, the notion of time is about the future. On the other hand, in Spanish:

“la una y cuarto”. It alludes the past. You’re looking behind. Because of this, when the own language has dominated the society, the country has overcame the adversities.

A silly thing such as time made people look ahead. It’s something from everyday life. This is why language is important. Not because of literature but because of this, because the way of thinking.

The eighties? Well, there’s something very important during the eighties, and that’s that Barcelona is nominated for the Olympics.

Why does Barcelona, and gets to hold the international Olympic Games? Very easy: because COI’s president did it as he pleased.

He, Juan Antonio Samaranch, was from Barcelona. He had a piece of land in El Prat that was the perfect location for the Olympic village.

The thing is that Barcelona is nominated for the Olympic village, and it can’t be backed out. Barcelona’s city council messed up the deal for him. Why? Because they had a linking

with a series of companies that had promoted El Prat de la Ribera in 1965 in order to remodel Barcelona’s coastal, from la Barceloneta until el Besòs.

It couldn’t be done back then, and 20 years after they find the great chance. That’s why the Olympic village was build there. Companies had lands there,

but it wasn’t a good location for factories. The land devaluated. One of the companies that took advantage of this situation was Renfe,

but it wasn’t the only one. The Free Trade Zone Consortium, Laforet, Motor Ibérica, Nissan nowadays, and more. They had huge pieces of building land there,

and this was the great occasion. And, since they can’t use all of them during the Olympics, years after they make up the Universal Forum of Culture. This speculative operation

that takes us to today’s Barcelona, is the most important event of the city during the ‘80s.

It’s not that I’m pro-independence, is that I’ve lived independently for years. I haven’t felt Spanish

since forever. I’m sure about it because I was recruited without a choice by the Spanish army. It was then when I realized that that wasn’t my army,

not because it was Francoist, but because it was Spanish.