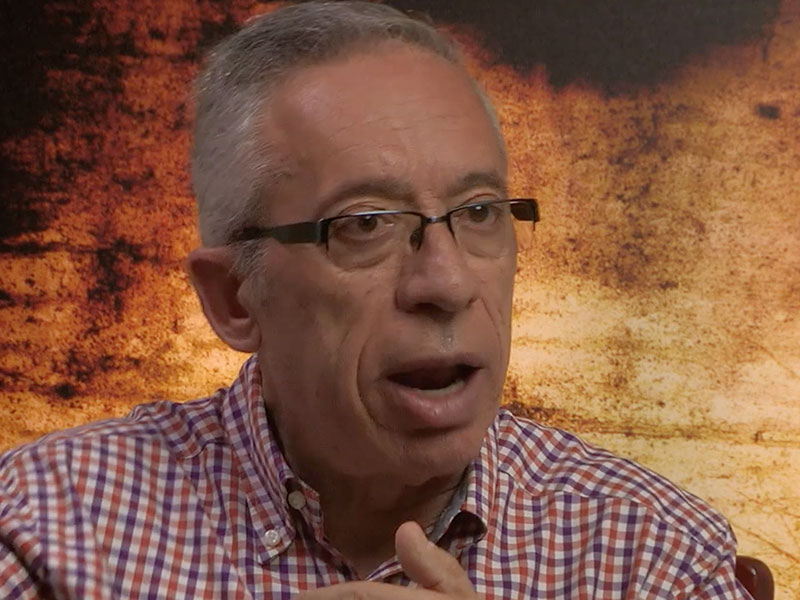

Ramón Alberch

Interviewed August 9, 2017 for Catalunya Barcelona docuseries.

Good morning, if you could please state your name and when and where you were born.

Ramón Alberch Fugueres. I was born in Girona, 1951.

Could you tell us a bit about your job?

I’ve dedicated my life, basically, to archives. I worked in Girona, in the Barcelona city hall, I directed the archives of the Generalitat de Catalunya.

I’ve also dedicated myself to the world of associations of archivists and now to the world of archives and human rights.

I’ve written about 30 books about history and archives, so far.

Could you tell us who was Ildefons Cerdà and why was he so important?

Ildefons Cerdà is a man, let’s say, of the first half of the XIX century. He was born in 1815 in Centelles and died, if I’m not wrong, in 1866 or 1865.

He studied engineering but had, as was common at that time, many interests. He was a man interested in politics, writing…this is, a man with wide humanist interests.

He was the great inspiratory of what was later called the Cerdà plan. In the sense that he was able to fuse the advanced ideas he had learn in France, Germany, with the need of Barcelona to access the strict scope of the wall.

His dedication was so strong that, even though he came from an upper class family, a family with no economic problems, he spent most of him heritage in his cultural and urbanistic initiatives.

A man with a difficult life, he died unfortunately the 1866, I think, in a spa, abandoned by his family. A man with a very tough and difficult life, in the sense that his ideas found a strong opposition. Maybe because back then they were innovative. In that sense, he was a groundbreaking man, who maybe had to pay in a way having to be a pioneer in many aspects.

You’ve mentioned that his ideas found a strong opposition. This opposition came from the social elite. In what way were his ideas opposed?

The Cerdà plan is seen in Barcelona as an imposition from the Madrid government. The city is an encircled city, like old regime, military cities, with walls.

The housing in unhealthy, with poor air circulation, lack of hygiene and difficult communication.

So they say, well, we have to tear down the walls, open the city up, which is a sign of modernity, and make an up-to-date widening.

He wins the tender and around 1860 begins the issue that a part of the Barcelona city hall and the aristocracy and bourgeoisie see it as a sort of imposition. On top of that, they dislike the plan because it brings some rationality: the grids, the inner patios… In Cerdà’s own words, let’s ruralize the urban.

He has an obsession with cheap art, air circulation, all that the old city didn’t have.

It was, then, a very little speculative project, thought in advantage of an ordered, very rationalist city. Maybe, in this sense, very Parisian in some ways.

That clashes with the bourgeois speculative interest.

With some people who thought that the widening of the walls should be done in favor of industry rather than housing.

There are also problems with the trade. Architects look poorly on the fact that the project was given to an urbanist.

Back then the idea of an urbanist didn’t exist, he was an engineer. An engineer designs bridges, designs roads, doesn’t design cities, that was a role that architects had always self attributed.

Despite everything, the project will come up again, with many difficulties, many issues, but it will be completed.

But it will find very little help from the city. Most of the time, he isn’t even getting paid his fee.

As I said, he spend all his heritage. He ended up divorced from his wife, the last daughter he had out of wedlock with someone else and he even acknowledged her.

A family life, for that time, very difficult. Now it would be seen more naturally, but back then not at all.

He is a man that dies without any kind of acknowledgement. Without any assurance that his project will be carried out, because he ends up dying five years after the project starts.

That’s very Catalan, or very human, that a man dies and isn’t acknowledged until later.

I’ve been able to see, in the historic archives of the city, all the Cerdà legacy and the Cerdà collection, and it’s an extraordinary work. Even with an actual outlook, it’s a titanic work. With a level of perfection in the drawings, a crystal clear definition, a modernity in the approach.

Now, he can be considered a leading figure. But he died, I insist, poor, abandoned, and without any sort of acknowledgement.

Could you tell us about the importance of Victor Balaguer? We think he’s the man who named the streets in the Eixample.

Victor Balaguer is a very important figure, in the sense that he’s a cultured man, an extraordinary writer. There’s a Victor Balaguer library in Vilanova.

He was the person who, from the city hall back then, during the opening of all the widening, was in charge of naming the streets. Now it seems something trivial, but back then it had great importance.

What he does now is using great figures of Catalan medievalism, very in line with the contemporary romanticism; or also cities or countries that in a way were tied to Catalonia.

You find Rossellò, Mallorca, cerdenya, the whole imaginary of the medieval age Catalanoaragonese empire and all the imaginary of the great figures that were in that moment. From taking Roger de Flor or Roger de Llúria to Ramón Muntaner, all the medieval Catalan leading figures.

So the widening is, in that sense, the imaginary of the turn of the century. The romanticism, the recovery of the Catalan tradition, the recovery of the Catalan nation.

Victor Balaguer may be very controversial in other topics, such as his double ascription, now he’s Catalan now he’s Spanish. He’s an odd man, but in that sense he’s the organizer that generates this symbolism in the widening regarding the denominations. Nowadays, it’s given very little importance. They just take Spanish provinces and put them one after the other, in most cases.

Back then it’s very considered, the widening is modernity but at the same time tradition, the recovery of the Catalan roots.

How did the 1898 disaster affect the Catalan economy?

In 1898 something happens, let’s see, to situate the disaster of the 1898. Spain starts losing colonies during the French war, the independence war in 1808-1815.

Even back then, the emancipation movements are very strong. Spain finds that, while it’s focused on the war with France, the colonies try to emancipate.

When the French war is over, they start sending armies there again. It’s a loss of youths, of young blood, that is also later one of the factors of discredit and critique of the whole restoration political regime.

Anyhow, what they do is send troops and Cuba and Filipins are the last two bastions.

They try everything. In Cuba, 20.000 soldiers die in the war, not to mention that in 1895 dies José Martí, the great Cuban leader. Even now the airport is named after him.

José Rizal, in Filipins dies too, by firing squad in this case, the same year. It’s a very tough repression and the 98 the United States, the classic phenomenon of the armored cruiser Maine, with the accusation that it has been sunken by Spain. Anyhow, there’s a clash Spain – United States with no chances for the Spanish armies and the emancipation happens.

What does this cause? This causes two things. First, it causes the loss of a captive market. That’s why the Catalan bourgeoisie, for the most part, was pro repression, because it was a controlled marked that served their interests without giving any trouble.

That causes, of course, specially the loss of Cuba more than that of Filipins, a phenomenon of loss of market but also a phenomenon of repatriation of capital.

There’s people who come back here with capital that will invest here. That mitigates a bit the impact of the crisis.

But it also makes the latent crisis of the restoration burst with all its strength. A regenerationist movement appears, there’s modernism. There’s a whole movement, from this point onward, of parties that openly question the oligarchic, dynastic and centralist model.

That’s a very important change. Further than the economic consequences, there are the politic ones.

Begins the crisis of a system that had stood more or less stable up until then and it bring another important phenomenon that needs to be kept in mind.

The army is very resentful for the loss and, from that moment on, the role of the army on the state will be very important, because it will be constantly looking after it’s good standing, its good name and what others will say.

This will be later seen in some laws, some attitudes from the army, an extraordinary amount of pressure from the army on the institutions.

What was the ‘Lliga Regionalista’?

The ‘Lliga Regionalista’ was a movement that is the addition of the Catalan center, a national center and a regionalist union that converge, in this context of regenerationst movement, and in 1901 the ‘Lliga’ is created.

The ‘Lliga’ will be the great party of Catalan civilized right through the first third of the XX century, in opposition to the other great party, the ‘Partit Republicà Radical’.

The ‘Lliga’ is the party of the government men. Prat de la Riba, the editor of the Catalan nationality in 1906, the great thinker of the reconstruction of Catalonia, the maker of the union of the diputations in the form of the mancomunity of Catalonia.

But the ‘Lliga’ is, above all, the cradle of the men of state: Prat de la Riba is a case, the second case will be Puig i Cadafalch, who is an extraordinary architect. We have a sensational archive from him in the Catalonia national archive, where there are some of his works in ‘Passeig de Gràcia’ of great value. There’s people who think those are Gaudí’s, many people see something good and assume it’s from Gaudí. Many are from Puig i Cadafalch, or Domenech i Montaner, another extraordinary architect.

But he’s also a politician. Puig i Cadafalch will be the successor of Prat de la Riba. Then, the third great personality of the ‘Lliga’ is Francesc Cambó, who is a politician that goes beyond the Catalan scope to irradiate its influence on a Spanish level.

It’s a party, on its core, of order, bourgeois, moderate catalanism, dynamic, but in that moment it’s a great novelty. It’s civilized right-wing, European, with ideas of democracy, of freedom. It’s a great change regarding what was there before, and that’s one of the big contributions of the ‘Lliga’.

With its ups and downs, the republic arrives which is when, due to their inside contradictions (inside the ‘Lliga’ are side by side a folklorist and traditionalist aristocracy with an illustrated and progressive bourgeois) splits occur and it weakens.

But it’s the great civilized right-wing, I insist because it needs to be said, in that moment it’s a feat. The great Catalan civilized right-wing [party] of the first third of the XX century.

Can you talk about the ‘Partit Republicà Radical’?

The ‘Partit Republicà Radical’ is the other side.

Completely different. Their leader, a very odd man of Andalusian origin, if I’m not wrong, Alejandro Lerroux. The ‘Partit Republicà Radical’, has even given name in Catalonia, to a somewhat insulting denomination, that is someone being a Lerrouxist.

Why? The ‘Partit Republicà Radical’ was Spanish nationalist, anti-dynastic, had a touch of violence and a touch of anti-clericalism. All mixed with a demagogy of a person with a huge ease of speech.

It makes you think of some current politicians, people without much substance but with a discourse of great verbosity.

He has memorable quotes. He was called the emperor of the Paral·lel, because the Paral·lel street back then was the place for Cabarés, bars, of the dissolute life where would also gather the underworld.

It was his movement space. A very famous quote from him, which he said in a meeting, says, go into the convents, lift the veils of the novices and lift them to the category of mothers. That was breakthrough in all senses.

But he has great strength. Why does it have great strength? Because the working class is starting to be non-catalan, not in a pejorative sense, but as its precedence.

It’s a working class that comes from Andalusia, Murcia, that have come to the Universal Exposition in 1888, they have come for the works that are being made through the city.

In 1908, the ‘Partit Republicà Radical’ is born, seven years after the ‘Lliga’, two years after the famous Catalan solidarity, a union of Catalan parties against the Madrid government.

Lerroux, in that moment, has a very loyal public. Spanish nationalist, he talks to them in Spanish because it’s a language that, for people who have come, is theirs. With that he makes a lot of confrontation politics between the Catalans and those who aren’t.

Here’s where the expression Lerrouxism comes from, when someone in Catalonia has made a movement, like the Andalusian socialist party in the 80s, they called them Lerrouxists because they divided people by their origin. They said, these are Catalans, these aren’t.

He uses that a lot, and finds a proletariat that thinks that Catalan and catalanism is a bourgeois thing and has nothing to do [with them], being not Catalan and catalanist is being a worker.

This simplification helps him gain strength, but he meets another opposed force that is the CNT.

The CNT faces him with toughness, but even then, in the Barcelona city hall during the years 14, 15, 17 and 20 they have a lot of strength. They lose it due to underhand business, business that is fuzzy economically, hand out positions to friends. But even until the republic, in the year 33-35, the ‘Partit Republicà Radical’ manages to govern a term.

With lots of splits. And when the republic comes and the war comes, it’s almost an extint party due to the different factions that appear in the face of a strong leadership, a diffuse ideology, a highly demagogic tone. But, it’s a party that during the first third of the XX century, especially in Catalonia, has an extraordinary strength and confronts clearly the ‘Lliga’, their opposite.

So it needs to be understood as the two big parties of that time.

It’s often found that the restoration authorities would entrust the catholic church to lend some services to people that, in Europe, were lent by the state. Could you tell us about what services were those and which were the parties responsible of bringing them back to the control of the state and giving them strength?

The needs of the working class, during the first third of the XX century, are astonishing. Improper housing, exploitation of the work of women and children, misery salaries, a very tough life, analphabetism, workdays of 13 to 14 hours a day. What does this make? It generates a very strong social anxiety.

What happens? The church had a tradition of charity-slash-beneficence ever since the middle ages. In the cathedrals, there were the ‘Pies Almoines’ that you had to give for the poor.

Then there’s the mendicant orders of monasteries, who went around the world asking for money to help the poor. That’s regarding this policy of helping the poor.

Then, there are all the parishes that move in that sense. What does the church do?

It has a historic continuity of lending services, maybe with a with a charitative will that’s not very equitative, not very just, but rather of religious doctrine, you must help the poor. In that sense, it could be considered not very modern, but with an extraordinary tradition and with governments that don’t help with those needs.

Why? The liberal and conservative parties, the ones that alternate on power, don’t see this need because they’ve always lived with this proletary or marginal class and the resources of the state have been poorly organized, so there’s not enough for that.

This consolidates the role of the church, and also leads to using evangelizer elements, matters of education and training.

The great religious congregations also open their own schools. Here it’s been lost a bit, but in Latin America there’s still the Pontifical Catholic university of Peru, the Xavierian in Bogotá, the Salle in…

This idea of education to attract and Christianize is also present. The church has then a double role: social service and indoctrination at the same time.

With a sector ever less given, because parallelly the workers’ unions get organized in the form of athenaeums, benefit societies, and other elements that we can talk about later.

This begins to get more organized when, at the beginning of the century, beings to appear the first legislation to protect the workers that will make the role of the church slowly diminish.

Despite everything, church will still, during the whole XIX century and part of the beginning of the XX, is the big purveyor of feeding and education services in the disadvantaged classes.

What was the Law of Cheap Housing in the 1911?

The law of cheap housing in an answer to a double-sided phenomenon. On one side, the piling up of people inside the city in anti-hygienic spaces, an extraordinary amount of people. There’s also that with the Universal Exposition and the linked growth works, there’s a very important immigration that when reaching Barcelona and being unable to find affordable rent in the city, a self-construction phenomenon began.

What does the law of cheap housing do? Tries to supply decent housing for the needier classes, that’s the idea. How does it do it? Two ways. One, via cheap rents. Two, via low interest loans that, in the theory, should allow them to afford it.

There are, from the 17-18 to the 25-30 plans like this.

There are in Barcelona neighborhoods and sectors where Eduard Aunós, Ramón Albo, areas of houses, In the rest of Catalonia too. But with a much smaller effect than it was predicted.

Why doesn’t it have that impact? Because in many cases to pay the rent you had to have a minimally decent salary, and to buy a house, no matter how much you are loaned, it still needs a high level [salary I suppose].

Then is when the legislation of the year 11 is renovated and the first savings banks begin to appear.

Specially the ‘Caja de ahorros y monte de piedad de Barcelona’, which is the great Catalan savings bank and will later merge with ‘La Caixa’, we all understand what ‘La Caixa’ is.

That’s the great supplier. In part, it’s seen as a social service, in part also as a business because despite the interest being low, there are interests.

It won’t have the expected impact in the numeric sense. The work is performed correctly, properly resolved, but it doesn’t solve either the ‘barracas’ issue or the piling issue.

But it leaves some singular buildings throughout Catalonia. Curiously, this idea is later resurrected by Francoism with the garden cities.

There are neighborhoods in Girona, Tarragona, with the same idea: a house with a small garden, trying to give dignity to the life of those who are most in need.

It’s an interesting initiative. Possibly it doesn’t have the impact, I insist, it would have needed for the thousands of people who are in a situation of need.

What were the Athenaeums and what function did they have?

The athenaeums are a space, this is, Catalan syndicalism takes a strong turn towards anarchosyndicalism. Among other factors, due to the ever existing conflict between the business associations and the labor unions.

The great representative of anarchosyndicalism is the CNT. There’s a moment, on the doorstep of the civil war, when it has 900.000 members, it’s the great labor union.

Way over UGT, which is created, I think, the 1888, but it never has the strength of CNT, which in its origin is a peaceful anarchism. Another matter is that it evolves towards a confrontation.

What happens in the athenaeums? They find that they need to provide services. They have workers, I insist, in some extraordinary exploitation conditions, especially in very deficient training [education?] conditions. They know that as long as the current level of analphabetism is maintained, this level of exploitation, there’s no future for the [working] class.

Then the athenaeums are a space for culture, for freedom, for education. Self-managed in most cases. There are still athenaeums in Poblenou, you can still find athenaeums in some neighborhoods that are over a hundred years old. They are created at the beginning of the XX century and still last, maybe with a different perspective, but the same idea: the athenaeum is the culture space and friendly societies and cooperatives are the spaces to lend services.

What do friendly societies do? They provide resources so that when someone has an accident or gets sick, they can have a remuneration and don’t end in the most absolute misery.

The athenaeum has a more cultural side. That’s also very related with the work of Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia and will result in the famous ‘Setmana Tràgica’ in the 1909 with the burning of convents. But there’s a very strong movement of training and education of the working class.

Some social critics have dubbed Barcelona barracopolis. Could you tell us a bit about this ‘barracas’ issues?

Barracopolis, I was reading about it the other day, is an expression that designed a journalist named Emili Mira in 1923 to design the city.

What’s the issue? As we’ve said, the massive arrival of people creates a very clear problem of housing. That leads to the creation of ‘barracas’ neighborhoods: Montjuic, later Pequin, ‘el camp de la bota’, el Carmel.

Places where there are built thousands [of shacks]. In the year 16 I think there were 6.000 shacks, in the 20 something there were 16.000 and around the 60 I think it’s 60.000.

It’s a phenomenon that grows and goes through the [first] third of the XX century, the republic and the civil war and reaches Francoism. IT’s a phenomenon that is removed during the time of the term of mayor Pascual Maragall, when the last zones are tore down and with the Universal Forum of Cultures is eradicated the last sector near the river Besós that still stood. We are then talking about a phenomenon that has lasted until ten, fifteen years ago.

What’s the issue? Around 60 or 70 thousand people is the estimated number that, around the 20s, lived in ‘barracas’, around a 5% or 7% of the population.

So it generates a social, human, and marginalization issue, a completely alternative city.

With all the phenomena of a ghetto, of being aside. I remember perfectly, as a young man, to have gone to Rio, in Girona, which was a ‘barracas’ area by the river. A flood came and swept all the ‘barracas’ away, there was an extraordinary death toll because they were constructed in the most lost, marginal places.

Many of them are moved out when the land begins to be valued. The first efforts are not so much social but rather that they occupied places that could have some value.

Curiously, in Girona they occupy Montjuic, in Barcelona they occupy Montjuic. Why? High ground, mountainous, where the attraction of going to live there was relative back then.

I insist, Josep María Huertas Clavería, a journalist unfortunately gone young, did a series of articles about the people who had lived there.

It is, of course, a very tough life. There’s no water, no electricity, no public service. Slowly some of them arrive. Some of the self-constructed neighborhoods have been dignified and nowadays you can go and find that life is half decent.

Sometimes, you can even think that the location isn’t half bad.

But at the beginnings, it’s terrible. Proof of this is the marginalization and poverty that comes from most of the immigration towards Catalonia and Madrid. It’s a national phenomenon, but in Barcelona, due to its industrial weight, the ‘barracas’ issue is much more evident and obvious because of the numeric strength.

Who were the people of order?

The people of order. The epithet people of order appears during the republic and the civil war.

What does it mean? It means that, in the face of the polarized conflict between first two political parties and the anarcho-syndicalism and the business union, it’s a very complex issue,…

…there are some people who, above all, asks for order. There’s a moment when, even people who could feel republican, with a strong democratic feeling, in front of the polarization, in front of the violence, the murders, the indiscriminate acts, think the only solution is order.

This becomes obvious with the eruption of the civil war. People who were sincerely republican, in front of some of the abuses perfectly documented nowadays, no point denying them, especially form the FAI (Iberian Anarchist Federation), What they say is, in front of this situation of misgovern, absolute insecurity, life and property endangered, let there be order.

That’s why Franco, who was repudiated and poorly seen by part of the Catalan bourgeoise, for some of them ends up being the solution against the misgovernment that takes place for a part of the period between the July 18th36 to the 37: control patrols, the committee of antifascist militias.

This, let’s say, uncivilized behavior of part of anarchism, with lots of violence and aggression, generates the repulse of part of the people who maybe would have been republican to the end but, halfway there, decides the only possible solution is order. Many of them go into exile. Many go to France and then move into the national zone.

I don’t mean the exile on the 39, where convinced republicans go to exile when they know what’s about to happen. It’s people who, around the 36-37, see that the situation isn’t in their favor and turn tail.

There’s Juan March, the Majorcan who will finance Franco. A significative amount of people, when seeing the danger, the seizing of factories, the collectivization, the danger of death, the shooting of religious people,…

…get scared. Some think that this situation gets them in danger too, turn around and move to Franco’s Spain, to Burgos… They change sides and that creates this generic expression of People of Order: those who want order above anything else.

According to Church sources, there were between 8,000 and 10,000 gang members in Barcelona at the start of the XX century. Can you speak about this?

Yes. That’s the phenomenon they call ‘pandillerismo’, gang members, what’s it about? It’s a very conflictive society.

The scene is an open conflict created by the huge pressure of the business association over the workers.

I think that, at the beginning of the [XX] century, the cotton industry was a 60% women and 20% children.

With workdays of over 11 hours and no Sunday rest. There’s a potent breeding ground for an open conflict, in which part of the underground, the delinquency and violence world, find the ideal ground to, disguised as conflict, pour all the contained violence.

Many of them even justify it. Some don’t, it’s crime that just survives on payroll of ones and the others in an open conflict of murder of businessmen and workers.

If I remember correctly, the death toll is, in the 800 attempts between the years 20 and 22, 12 businessmen and union members. Violence is present in the city and this crime finds room to grow, so to speak.

Most of them are just criminals, but others are smarter and dress up in a sort of ideology.

They say that the working-class violence is the answer to the secular abuses of capitalism and the burgeoise.

The core idea is that they have been exploiting us for 200 years, now it’s our turn.

So working-class justice is a just justice, and killing a business man, a politician, is part of this just idea that now it’s our turn to make them pay for our suffering.

Indeed, they reach some extraordinary force, which creates a city with very strong insecurities.

There’s a movie that portrays this, the tension situation. “La Saga de los Rius”, which was famous many years ago, was the life of a businessman who was constantly in mortal danger and how he had his group of underworld gunslingers, of gang members who defended him from this possible attemtps.

In order to control this lower classes, there were a series of laws and practices that could be considered draconian, such as the ‘ley de fugas’, could you talk about this?

It needs to be understood that, in the state, the army is hypersensitive. The army keeps pressuring to make legislation that covers its good name.

For example, when Cuba and Filipins are lost in 1898, a Catalan satirical weekly, named “¡Cu-Cut!”, publishes a joke and soon after is assaulted by the army and torn apart. From that moment on, appears the law of jurisdictions.

It’s a law, which will last until the end of the republic, in which any comment against the army, it’s emblems, the good name of the army is penalized.

So we are in a context of a distrusting army, that has lost a war and sees that the citizenry blames them in a way of losing the war, which will later derive in their colonial wars in Morocco and towards Africa, which will keep them busy. But they will always keep inside that it’s unfair that they are accused of having lost the colonial empire.

So there’s a government that believes that the only way to eradicate the conflict with the working class, especially the more violent sector, is simply through legalized murder.

Here’s where appears the famous law of jailbreaks. What it does is simply legalize the selective murder of syndical leaders. Between the years 16 and 20 over 400 people are killed and the technique is very clear.

Detention of a labor unionist or a worker, giving him a chance to escape and then shoot him, stating that he had tried to flee. This practice is perfectly well documented. Primo de Rivera, in a document, explains it. He says, no, no, what we need to do is arrest them, give them a chance to flee and when they do shoot them. It’s the only way, he says, to finish this scourge, this cancer that is anarchism.

So, the law of jailbreaks is another tool of the state to try to put out the fire by pouring gas on it.

That is, going into the battle of the selective murder too. The state turned into actor of violence, beyond than the law. That’s the great issue in this period.

The state should always try to keep at least the form, the rights, the law. It’s a state that thinks it is legitimate to play the same game they do. So it uses the underworld, the world of gunslingers and spies, to end this movement.

They think they have absolute legitimacy and that every act they make is right and proper.

At the beginning of the XX century, what was the Guardia Civil and what was its role?

The Guardia Civil is created in 1844 by the Duque of Ahumada.

It follows a line until the beginning of the century as a rural guard. The idea back then is a unified military force, found throughout all Spain so it has a national character, that keeps order in the rural areas.

This is a time when there were still order and security problems, assaults, crime. The Guardia Civil is a the great armed force that will carry on with no trouble, currently being the oldest police force. The Cuerpo de Policía Nacional comes later. From 1844 to now, it’s the oldest police force.

What’s their role back then? It’s a tool of the state. It’s a militarized force, made up of people with humble origins, little education and a badge of honor and principles very instilled, the whole military discipline and honor of the force thing.

It realized police tasks in rural areas, which back then were an important part of the population. Slowly, it will update, taking other tasks of investigation, but well into the early XX century, it’s purely a security force, a force of politic and ideologic control in the hands of the government.

What was the sometent militia?

‘Sometent’ has its roots in the medieval age, precisely due to the creation of the Guardia Civil and later in towns the ‘Policia Local’ and the ‘Guardia Urbana’, is when the ‘Sometent’…[Here he breaks off and starts answering again, but doesn’t leave much time]

Sometent was a popular movement of medieval roots. It consisted in, when there was danger they called the ‘sometent’ with a bell ring and the townsfolk had weapons and would come out to defend the collective rights in front of the impossibility to have other security forces.

Then, the downfall of the ‘sometent’ is directly proportional to the implementation of the Guardia Civil.

However, Fraga Iribarne, as minister of internal affairs in the year 1970 something, did a symbolic act of giving up of arms of the latest sometents.

It’s left as a more folkloric force. In a given moment, they would go help a neighbor, a bell rings and it’s more a short distance protection, on a neighbor level. But on the medieval age until the XIX century it’s a popular body, made up by the people to defend the interests of society, of the town.

Created by people of the town. My grandfather belonged to it and they had a weapon, a permit and it was the town’s self-defense.

As the Guardia Civil gets implemented, the role of the ‘sometent’ decays and ends up being something folkloric.

By the end they have a suit and a weapon, but it lasts, officially, if I’m not wrong Fraga Iribarne definitively sanctions the end of the force the 73 or 74, before Franco’s death. Because he considers that it is the state’s task to carry out the functions of protection and vigilance, not a civil force.

Who was the König baron and why is he remembered?

The Baron of König is a man who is remembered, he’s a man of German origins, I think, some say Austrian, but it doesn’t matter.

He appears in San Sebastián in the 20s. A man who comes from the world of casinos, comes to Catalonia and is a man who is a double agent. There was back then an organized group of paid gunslingers by the business union to fight with the emerging labor union that was the CNt, and what he does is a double game for his economic benefit with clear [methods]: infiltrate people in a sector…

He becomes good friends with Bravo Portillo, who was the leader of a group named the Black Band, who was the great group of organized violents.

When Bravo Portillo dies, the Baron of König raises himself as leader of that sector. He gets, for a long time, some huge economic benefits, a brutal economic level, and a very strong influence. All through this shrewdness, intelligence, of moving like a spy who, on one hand infiltrates the working-class side but also, if needed, favors an attempt on the business union to later be able to generate a response.

He’s a very feared man, in that period, for his great influence. Especially during the 20s, he has a very strong influence in Catalonia.

He exiled himself, if I remember correctly, to Paris and died the 45. But not long before, he was smuggling Nazi refugees who wanted to leave Germany when they saw the end of the war coming. He is then a man about the life of whom could be written a magnificent book.

Who was Martinez Anido?

Martinez Anido was Barcelona’s civil governor between the 20 and the 22. Martínez Anido is the man who brings the labor union-business union conflict to its apex.

He is the man who inspires the free syndicate, which is a crime syndicate paid by the business union, and a man obsessed with finishing the CNT in every way inimaginable.

Think that the period he was a governor, I think, was 20-22. Afterwards he is demoted, even retired from the army and goes to live in France.

But after Franco’s victory in the civil war, he is a minister in Franco’s first government, he is returned to a good standing.

What does he do? Bring to its apex the confrontation with the most absolute violence. During his period there are about 800 attempts, and about 200 labor unionist die, some of them important. In the year 20 is murdered Francesc Layret and in the 23 is murdered Salvador Seguí, ‘the sugar boy’, two huge referents.

There are also murdered 100 businessmen and 50 policemen, the statistics are frightening. It’s the great conflict especially, if we look at the numbers, with most losses for the working-class side and especially for the loss of two mythic men for the working-class referent like Francesc Layret and the Sugar Boy.

But he’s a man that, in the end, around the 22, seeing that it has all gotten out of hand, that violence breeds violence and an extraordinary violence spiral has been entered, when the Primo de Rivera dictatorship arrives, he’s publicly retired.

But I insist, during Francoism he’s recovered and ends up having important posts, even being a minister.

So great were the dangers of laboral accident that, even the Vanguardia, a rather conservative newspaper who doesn’t usually pay so much attention to those problems, criticized those things. Could you tell us about the laboral conditions of both adults and children in Barcelona in factories and workshops?

The labor situation is terrible. There are workdays of 13 or 14 hours, the salaries are miserable. If you look at the prices of the basic products (bread, vegetables, I don’t even mean meat) their salary is gone with a very basic diet.

With improper housing: in the old neighborhood, narrow streets, lacking air circulation, lacking hygiene, human piling.

This phenomenon forces the state to act.

Finally, in the 1900, a law is made to protect [the workers], specially from labor accidents, the great scourge.

Why? The machines are rudimentary, with great human intervention. This law in 1900 is considered an advancement yet says things like: women can’t work more than eleven hours, so they could work up to eleven; children under eleven couldn’t work, which means they were made work; and even talks of imposing the Sunday rest.

That’s the 1900, so to sum up: eleven hours minimum [maximum] work, minors of eleven can’t work, and Sunday rest.

This means, what’s the real situation? Eight and nine years old children are exploited, there are workdays of 14 hours.

All of this, of course, with a normative that is barely observed by the businessmen, the law is made in 1900 but there are still exploitations.

I’ve seen the archives. You look at documents of the ‘Maquinista Terrestre i Marítima’ in the industrial Spain, you take a look at the workers lists and you see children of 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 working in the factories, women…

Why? A woman earned less than a man and a kid earned less than a woman. So that brings what we mentioned before, in the cotton industry 60% of the workers were women and 20% children.

It’s a brutal children’s exploitation. What does that cause? Children that barely sleep, awfully fed, there are still recurrences of epidemics like cholera, typhus…

Labor accidents? Poorly trained people, old machinery, physical exhaustion, endless workdays…

Ildefons Cerdà himself, when he does one of the studies to build the Eixample, talks about the life expectancy as a worker in Barcelona, and I think he says that life expectancy is 33 or 34 years.

So we are portraying a situation that, without condoning the sometimes violent act of the working class, it’s obvious that they had all the rights for the demands they had for years.

From the 1890s onward, working class anger manifested through bombings, strikes, barricades, anarchism, anarcho-syndicalism and revolutionary fervor. How did the urban problems discussed above lead to these different forms of protest, and ultimately the brief period of collectivization occurred during the 30s?

There’s a very strong evolution. We have talked about gangs. That evolution arrives too with an expression of underground of that period.

There’s a book of a man, whose name is Federico [Vázquez] Osuna, if I’m not wrong, named “Baixos fons i anarquisme” where he portrays really well the situation of degradation that is taking place and how it reaches a moment of a revolutionary eruption.

Here we need to look a bit at the situation. All the underground and the crime world is transmuting to the world of politics and some of them end up having posts.

War, in this regard, is the great liberator of some hidden forces that in many ways appear clearly later.

Specially in the period when anarchism has a lot of strength and the FAI is very important, control patrols, as I said before, the topic of antifascist militias.

All this generates the appearance of many people, some of them of very low social origin, a strong analphabetism. But it also generates some of the myths nowadays.

In this sector there are mixes as visible as, he’s always spoken about, Ramón Mercader, the Catalan who murdered Trotski in Mexico.

But of course, to understand him you need to understand his mother, Caridad del Rio. A women born of Spanish parents in Cuba, an aristocrat, who is married to a Catalan industrial, Pau Mercader with whom she has 4 children. Suddenly, in the atmosphere of the Paral·lel, she is tainted by the revolutionary ideology and ends up being a brutal Stalinist.

She raises her son Ramón and persuades him to kill Trotski in Mexico, and that’s the famous murder of Trotski.

That case gave way to three fantastic books that I’ll take the liberty to mention. One is by Leonardo Padura, named “El Hombre que Amaba a los Perros”, which is a novelized biography of Ramón Mercader. The other is a thesis by Eduard Puiventós titled “L’home del Piolet”, because he killed him with an ice axe, he put one in his blazer and buried it in his head. And a third one, that was published recently, by Gregorio Luri titled “Asaltando los Cielos”, which is about Caridad del Rio/Mercader, which was his husband’s last name.

It’s the life of this kind of people who transmutes either from aristocracy, which is rare, or from the underground to the politic life.

You also find many people who holds posts of responsibility form very low social origins, with little education and a discourse, in this sense, very strong.

One of the elements that is also very clear is the famous Escorza. Manuel Escorza del Val who is a leader, let’s say, radical who will settle in casa Cambó in via Laietana.

He is the famous author of a murder where he kidnapped some Marist brothers, made the Marist French school pay an amount and sent them back dead, stating that he was giving them back, just that they were dead.

This man ended up transmuting and going to Chile, where he became a cultural journalist.

Lives like that. All this mix of low origins, and ,in the case of Escorza, he had poliomyelitis and was convinced that this was a sentence for being poor.

So there are ancestral, incubated hatreds; many vengeances. It’s a brutal mixture and that will finally lead to the collectivizing movement that can be read in two different ways.

Some read it as a pioneer act, that inspired other movements. Many say that the movement of Tito in Yugoslavia is quite related because he had been a brigade member during the Spanish civil war.

There’s also the side, which is true, that part of the collectivized factories, if they hadn’t been refitted to make bullets, bombs and weapons, wouldn’t have functioned, because there was no preparation to carry that out.

It’s something that is still hotly debated, but it’s true that it is a novel experience, extraordinary, for example in the world of cinema, the mass media, it was easier because there was prepared people in that sector. In the world of factories, the achievements they made are more questionable.

Despite all this, it’s the result of an upset society. A society that is in war, and that was the great problem of the republic, with the enemy, Franco, but are also in war, in Catalonia for example, against their own society. That’s one of the strongest criticism nowadays towards anarchism and the FAI.

They maybe spent more time chasing the inner enemy than fighting the outer enemy. That’s probably one of the causes of having lost the war, this duality of action.

You’ve mentioned the underground, could you talk about this a bit?

The underground, basicall, as I said this book by Federico Vázquez Osuna (now I got the name right) is extraordinary. He had a chance to look in the court records, and portrays very well how people who clearly came from the crime world, …

… a mixture of natives with people came to Catalonia in the last few years, especially from Murcia and Andalucia, but with a common component of radicalism, a certain amount of ignorance, and, especially, a load of historic violence, of believing they had to make them pay the harm that had been done to them.

That creates all sorts of characters. From the straight up criminal, like some that robbed banks and worked kidnapping; to those that evolve and end up holding, like Aurelio Fernàndez, publics posts in the Generality, one even reaches the post of Councilor.

What happens with this sector? It has been questioned, and this book helps see the dark and light of this sector. Because this people, beyond the verbal ideals of justice, egalitarianism, socialism, etc., by the end of the war, the 38, many of them disappear.

Many of them leave with lots of goods, too. It is explained by García Oliver himself, and important leader.

In a certain moment, the Crédit Lyonais in Lyon opens in a Sunday so that there can come in from Catalonia jewels, money…

There needs to take place more investigation in this area.

Why? They say that they took the money because once they are exiled they need to rebuild the movement, need to help with that, but here there’s also a lot of personal enrichment.

It’s difficult to see who was who here. Tarradellas has also been accused that he left with money, but the truth is that by the 60s he was living in misery.

García Oliver, Aurelio Fernández, have also been accused of leaving with lots of money and jewels, the products of seizing and kidnapping.

The line that is tough to see, and the book helps see it (“Anarquistes i Baixos Fons” or “Baixos Fons i Anarquistes” [the right one is the first one]), is the line between the ones who really fought for the ideals and the ones for who it was a way to get rich.

Many of they, truth be told, live in the exile for 20 or 30 years without working, so some of them…

A very strong group also leaves for Taumalipas, Guadalajara, Puebla; Mexico, and settle there apart from the world.

Others go to Cuba, others to Chile, many stay in France.

It would be interesting to find out what’s true in that they take the money to help the exiles, which is partly true, and what’s true, which happens in some cases, of pure enrichment.

They have taken the chance and enriched themselves. There’s a book titled “Entre el Roig I el Negre” that explains the diary of an anarchist gunslinger, named Josep Serra.

When they went to seize houses, the orders were to burn everything. But this man, in a country house in Vil·lafranca, stored valuable things, jewels.

In the year 38 he took a ship, went to London, and there lived for 25 years for free spending those valuables. I mean that there’s a bit of everything.

Why is it so tough, and I’m about to end, to find out what happened? Because in the period they were in power, the years 36 and 37 of the more radical sector, they burn almost all the court records.

Because they know that there were records that charged many of their militants.

And, very smartly in the case, they are aware that the records are an arsenal of information, a space where there can appear documents that implicate them. In an organized way, they keep giving orders to the archivist of that time, Duran i Canyameres, that he gives them the records of the years 10, 15, 20, 25 and burn them all. A small part is conserved, because that man managed to save part of it.

It was a way to go unpunished. So, their conscience must have been restless when they burned twenty years’ worth of court records.

With the excuse that it could be used with evil ends by others, what they actually do is clean the past and consecrate impunity, and we have those doubts of who was who in certain moments.

[second round of questions]

Can you tell us what happened in July 1936?

Yes, July 18th, 1936 is the moment of the upraising of the troops led by Mola, Franco, against the Republic government.

That was a phenomenon that had been incubated for a time. There was an open conflict of the more conservative part of Spanish society and the army against measures that, from April, 1931, had been imposed by the republic.

Regarding religious freedom or a society less controlled by the church, regarding social reforms, regarding the autonomic statutes and the Basque country…

This is, there had been growing a very strong ill will against the republic.

The republic really took a completely wrong choice. The more hostile military leaders were sent far away: Franco to Africa, Mola…

They sent them far away instead of keeping them withdrawn. But they learned the lesson well during the transition, Adolfo Suárez, when he found out that there were military groups gathering, what he did was carry them all to Madrid so he could keep them under control.

This time they learnt the lesson, but not then, they thought sending them away…

What did that do? Open the way for them.

Mola, from Navarra, Franco, from Morocco, raise up against the republic.

A part of the army and a part of the Guardia Civil, stays loyal to the republic.

That quickly causes a rift where a part of Spain is the National Spain and the other the Republican Spain.

And on the July 18th, 1936 officially begins the civil war.

In Catalonia, they manage to stop the military coup with help from the anarchists. And here is when the anarchists gain all that strength.

Because it’s them who, in a way, enter the barracks, take the weapons, and they claim to be the defenders of the Republic.

And that gives them a power, weaponry and freedom to act that they will use almost until July 1937.

It’s the beginning of the civil war which, as everyone knows, ends up February 39 with the final defeat of the republic. The war has many ups and downs.

The most important is that, since the allied forces decide not to intervene in Spain, despite some Russian support properly paid for, the republic is limited to its own forces.

Meanwhile Francoism has the support of Mussolini, the army, especially Germany and the Italians to a lesser degree.

Spain is a testing field for what later is the [second] world war.

The Germans come here to train. The German and Italian role in is key in Franco’s victory.

The pretended allied neutrality condemns the republic, beyond their own mistakes which I have already mentioned.

Especially in Catalonia is maintained this double war. There’s people who, instead of going to the frontline to shoot, they prefer to shoot here going after chaplains and seminarians.

This is a simplification, but what I mean is that beyond their mistakes, on a geostrategic level, I think the allies make a mistake.

They see the movement as too radical, too much in the hands of communists and socialists. Deep down, they think that a victory of the left isn’t within their interests, and without saying so don’t stop helping the Francoist regime, which later they will tolerate until the year 1975, when general Franco dies.

What were the medieval walls and when and why were they tore down?

The cities, in the medieval ages, were walled cities. They are cities in constant conflict.

Sometimes, they even have a double wall. The more traditional one from the roman age and a second, stronger one from the medieval age.

What did it create? It created strongly defended cities, with entrance gates to get in the city and therefore a strong control of the coming and going, but also an extraordinary demographic pressure.

Building inside the city created all those streets that still can be found in Barcelona around the Boqueria market plain, where you want, that have those archs, what did they do? Those were streets over which they build an arch and it was built upon.

There’s an incredible overpopulation, the density in the city is brutal, in detriment of air circulation, hygiene, like we said, piling, lack of health, all these elements.

All this, for a while, is reasonable. The Raval was the out-the-walls of the city, from Rambles down, on the right side, was all the area outside the walls.

When there was war, people came into the city, when it was over went out, it was a constant rebuilding. During war, sometimes the neighborhoods around were devastated and built again. That’s a phenomenon in Barcelona, Girona, all the walled cities.

Until there’s a moment when war changes its conception. The weaponry is so sophisticated that a wall, in a way, can’t resist it.

We need to think that, in many occasions, the attack was made with bombs with some explosion but they were made for impact.

They were solid pieces that kept hitting the wall until they tore it down.

Later came the explosive bombs, but those had a relative importance.

It’s the moment that, specially from the turn of the century, there’s a strong modernization of the weaponry that makes…

First, there’s no open war with France, who was the great rival, the great conflict; or the wars between Catalonia and Castilla, that was all over.

Then they see that what the wall does is constrict the city, it’s a corset that keeps it closed tight and begins the discourse of “Down with the walls”, a sort of regenerationist discourse.

That begins in 1860 and carries on.

The Cerdà widening is actually the result of this idea, saying, “tear down the walls”. That drags on, they tear it down by parts.

The cities that took longer to do this have preserved a lot of wall. In Barcelona, you can find some if you go through the Banys Nous or alike streets, if you go into bars and restaurants, they have a piece of the roman wall.

Here the roman wall is better preserved than the medieval wall, because back then it was used to build.

By the cathedral, in the casa Ardiaca, the historical archive of the city, the whole of the foundation downstairs: the roman towers, the roman wall.

That is, the roman wall is better preserved than the medieval one, because back then the roman one was used as a load-bearing wall.

Everything was reused. In the moment diggers appear, this ends, everything is torn to the ground. Back then, it was important to reuse.

From the turn of the century on, with the Cerdà widening, the walls are torn down a new city is opened.

Some cities, for example, Girona has a wall, Montblanc has a wall, Tarragona has part of a wall. In Barcelona, compared to how much wall it had, it could be said that there’s no medieval wall preserved, but curiously the roman one from the century I or II before Christ is preserved whole.

Maybe hidden in homes, but it’s still visible in some parts of the city.

What effect did that have on the working class and the elite?

The demolition of the walls, what it does is open the city, it grows.

Barcelona is still a small city despite that. It opens up towards Barcelona’s plain, so to say.

Many of the industry had already been moving out, Sant Martí de Provençals, during the second half of the XIX [century], was known as the Catalan Manchester.

There was a bigger percentage of industry there than there was farm work. In Sants, there was a[n industrial] scale.

It’s those famous towns that in 1898 Barcelona adds to create the greater Barcelona. Barcelona was a small city and here we have a double phenomenon: the demolition of the walls and the annexing policy.

They annex Sant Andreu, Sant Martí de Provençals, Gràcia, later Horta in the 1907 and Sarrià in the 1923. Barcelona grows because it sticks to its surroundings, and the wall is the element that allows for this connection.

Before, Gràcia was far away. The ‘Passeig de Gràcia’ is opened, that goes up until the Main [street] of Gràcia. In Sants happens the same with the Sants road.

The demolition of the walls articulates an expansion that by the 1898 was already very visible because, despite the wall that was left, the city had already been growing out of the walls. What the demolition does is reconnect the urban fabric and create an almost continuous conurbation.

In 1898 is when they finally get a decree from the state government by which they are annexed [to the aforementioned towns].

That’s why, the current model of a Barcelona with districts answers to this idea: there’s the district of Sant Martí, the district of Sants, the district of Gràcia, the district of Sant Andreu, [the district of] Horta…

Because it answers to a decentralized city, a city that’s an addition of cities.

The socialist party, during the term of Pascual Maragall, was able to see well that, in order to have no independentism issues inside Barcelona, they needed to make a decentralizing policy.

There they were very smart to move in advance of a very reivindicative neighborhood movement, with their own history.

With this they saw that they could feel from Barcelona while also being very tied to the neighborhood. There are still elderly people in Sarrià and Sant Andreu who you can hear them say, “Today I’m going to Barcelona”.

Because they still have that idea of going to Barcelona, since they were actually independent towns, in that sense.

What can you tell us about the 1888 exposition?

The exposition of the 88 is an important exposition… Barcelona has two universal expositions, the one of the 88 and the one of the 29.

The one of the 88 is the one that affects more the area of Montjuïc and creates some buildings. Back then, the 1888, a Universal Exposition brought two important elements.

Nowadays, it’s seen as a brief exposition, you build and then demolish everything.

In Sevilla they wanted to keep a part of what had been built, but in the end they had to demolish half of it, because there are so many buildings left unoccupied.

Back then, the idea was the opposite: to be able to build great things that were to be reused.

The Montjuïc Palace is now the National Art museum of Catalonia.

Part of the facilities that were built are now museums, others are barracks, others are schools.

It generated an extraordinary amount of construction, which is why one of the first strong immigratory waves comes with the Universal Exposition in 1888, when all of a sudden, in a few years, they need to build.

Back then, they didn’t build in an ephemeral way. That means that may of the buildings were made of brick, with a certain solidity and modernity.

In that sense, it’s one of the first modernizing phenomena of the city.

It generates lots of job, a strong economic activity and refurbishing of parts of the city that maybe weren’t well fit. The whole area of Montjuïc in that case, which emerges as a new center.

There are made buildings that, I insist: nowadays are in perfect condition and have public uses.

Could you tell us about the historic part of the city?

In the historic center of the city there’s the Jewish neighborhood, found behind the city hall.

There’s this whole intertwine of medieval streets that has also suffered important changes.

One of them is the opening of the ‘Vía Laietana’. Back then it was an operation with the target of creating a commercial city.

What they did is open ‘Vía Laietana’ from the sea to Uquinaona square. To do that, they break with all the streets and alleyways that were there. Otherwise, now it would still be like the streets we see in the old neighborhood of Barcelona, the ‘Pi’ square, the ‘Petrixol’ streel, all those streets and alleys.

All the city, in this sense, was like this.

‘Vía Laietana’ is the first big opening, which is also used later to put the subway through it.

That is one of the strong operations done that have a strong effect. The other phenomenon is that, during the 50s, they tried to turn the center into a museum.

So, they make works that aren’t appropriate, trying to make it look like they are old.

For example, one of the most photographed places in Barcelona is between the Sant Jaume square towards the cathedral square, by the Generalitat palace, where there’s a bridge that everyone photographs but it’s from the 20s.

It was done to join both sides of the street, for communication issues, in what was then the Diputació. Everyone is taking pictures of it and it’s only from the 20s.

There’s a joke from back then that says: “I’m looking for the Gothic Quarter”, says a tourist, and a citizen answers “Ah, the Gothic Quarter? It’s that thing that’s being built now in Barcelona.”

Because, actually, the whole façade of ‘Vía Laietana’, that you can see like a wall to the left, it’s all reconstructed.

It’s a work copying gothic but done after Francoism, in the moment Francoism starts.

Even though, it’s a neighborhood that still holds some value, especially in the inner, narrower streets, that are preserve better what used to be the medieval city.

Now, there are these two big interventions. Strictly the Gothic neighborhood, the cathedral and its surroundings, that is where people stroll the most, and ‘Vía Laietana’ as an operation, back then, with industrial and commercial goals. Having a space inside the city like the big European cities, like London has its business space. A space that failed, there are few companies left. Most of the buildings are for housing currently.

You’ve mentioned the Jewsih quarter, could you tell us more about it?

Yes, of course, the Jewish Quarter…

In Catalonia, there was a very important Jewish population ever since the X century.

And the most important Call, that is, the neighborhood, was the one in Barcelona.

The one in Girona is very notable because Girona has been able to sell it well and it has become a touristic landmark.

Maybe because it’s in a great location, it has been properly restored and is a referent. In Barcelona, curiously, the Jewish Quarter was, for sure, the more important one in the Crown of Aragón.

It had had as much as, counting low, 8 or 10 thousand inhabitants, had a synagogue, its butcher spaces, the public baths…

It was a strong society. It was mainly located behind what now is the Barcelona City hall, those streets where even now there’s a Call street.

To the right from the ‘Boquería’, reaching even the Ferran street, which is also a street opened later, had been economically bursting, they were negotiators, lived from loaning, but also other activities.

Until their expulsion the 1492, it’s an Aljama, that’s their government. It’s a self-government that is acknowledged and respected.

Why? In part because they are the crown’s loaners and that gives them an important role.

But that also creates a conflict since, being loaners, many Christians are indebted to them, which generates…

…in part, the continuous attacks on the Jewish quarter, 1331, 1391. The progroms during Easter, the moment of maximum religious excitement, when attacking the Jewish quarter was an acknowledged classic practice.

In this sense, the Jewish Quarter in Barcelona goes from 1391 onward in a downslide, as there is a very strong attack, and in 1492 the expulsion is the last nail on the coffin.

But the neighborhood is still there, but curiously it’s not often in the mind of Barcelonese people and tourists.

Where there was the synagogue, there’s now a sort of cult space, but it doesn’t irradiate the strength than others do, like in Girona or Tortosa.

But it had been very important for the Barcelonese economy during the medieval period.

Who were the Laitanii?

I know they were a tribe, but I can’t say much more.

Could you tell us about the air-raid shelters that were built?

Yes, during the civil war there was the practice, in the face of the indiscriminate bombings, to build air-raid shelters.

Many of them were made digging, that’s why there were many in Poblesec, in the mountain, but others have been discovered elsewhere in the city.

But the one in Poblesec is the best known one, because since it was built into the mountain, it can be visited, there are some that can be visited.

What did they do? It was a digging either underground or using a mountain where there were tunnels, seats, basic illumination, and it was there where people took refuge during the bombings.

They built lots of these, up to the point that the practice of the Catalan refuges is so strong that, during the second world war, in London they copy, in a way, the same technique.

There’s a service, a person, who investigates this and, so far, has found 70 something.

Some have been buried with times, breached by constructions or some of them, curiously, while digging for some constructions have been rediscovered.

I insist, that the shelter in Poblesec is the most widely visited, they could set it. There are also in Sant Andreu and other places in the city.

But maybe, for those who want to know what a shelter is like, the one in Poblesec is the most important one, because it’s very well preserved and you can fit 300, 400, 500 people while the bombing lasted.

When the bombardment was over, everyone went home. Then the alarms would sound for a bombing, and those who could reached it.

The subway was also used, but in this case, these are built specifically as shelters to protect the lives of people.

How was the bombing of Barcelona talked about in newspapers?

The bombing of Barcelona is widely known because it is a bombing on civilian population, partly attributed to the Italian and Francoist aviation.

It’s a moment in the war where there is nothing held back, no respect for the civilian population.

The war has reached a point where Francoism just wants to win the war whatever the cost.

And the bombing of civilian locations becomes commonplace. This is widely talked about because there are recordings, there are photographs, it’s quite documented, especially after the 38, the constant bombing on Barcelona, which will be an element that will make many people abandon the city.

It has a part of terrorizing people, scaring them. It’s sudden, you hear planes, they make you turn off the lights at home and hope we’re lucky and doesn’t fall on our home.

Or we go running to the refuge.

It also has a part of demobilization, of people who went to live to the countryside because it was so tough in the city. That’s explained by many contemporary chroniclers, many writers, that those who could sent them off.

But the bombings, I insist, have been very visualized since they have been documented. That makes them more real, in the sense of movies and photographs.

And, especially, the witnesses. Xavier Benquerel, many writers who explain the experience of being at home. People who wouldn’t move from their place, they said, “It doesn’t matter, I’m staying here, and if a bomb falls, bad luck”.

About people who had this constant pressure of going to the refuge and out of the refuge.

Regarding Reial square, what’s the difference in reputation 100 years ago and now?

The Reial square, of course, its own name says it all. A square with gateways, prestige, an embellished construction for the time.

Think that in Reial square, in the 60s near the 70s, lived Mario Vargas Llosas, lived Gabriel García Marquez, there was a time when Lluis Llach lived there, known artists of the time…

It was a very Barcelona-like square, with prestige, with an inner room.

With time, it has degenerated a bit and it’s a troublesome square: constant police patrols, crime issues, drug issues, if you go to have a drink there the police advice you not to leave your stuff around.

It has become a shady place in Ramblas. It’s been improved but in order to eradicate the small drug dealer, the petty criminal, they have swept away the gardening, a much more beautiful space.

They have, so to say, concreted it. Leaving the fountain in the middle and the rest concrete to have a better view.

So it’s a square that, due to the pressure it has suffered from crime, small time drug dealers, has moved from a valuable place, with proper housing and famous characters living in there…

…to a place that has lost its status, has lots the value it held.

Even though, it’s in a great location, it would be a fantastic place to live if it weren’t for the security issues.

Why so many international brigades?

In the civil war, there’s an important phenomenon that are the international brigades.

Why does this happen? The international brigade has a double reason.

It’s that ‘Proletarians of the world join’, help us fight against fascism.

People from the United States, from Cuba, from Germany, from England, from very different countries come here to give support to the republic.

One of the reasons is ideologic. They see that Franco’s movement is in line with fascism and Nazism, and that a radical right-wing movement needs to be confronted, in that sense they are a bit visionary.

There’s a part of adventurers.

There’s also the strong reaction when the allies declare that they won’t intervene in the Spanish civil war. People say, “if our countries won’t intervene, we will go there”.

Here comes fantastic people like George Orwell who, besides having written 1984, writes a fantastic book that not many know called “Homage to Catalonia”, and it’s his experience there.

Here also comes Ernest Hemmingway to fire some bullets.

Here comes too a character as sinister and strange as a Cuban named Rolando Masferrer, who ends up being a mobster that is murdered in Miami with a bomb.

Many kind of people come, but the great majority, besides some adventure seekers, are people who believe in a universal cause of justice and equality and think that we are fooling ourselves if we think that the fascist and Nazi issue is a Spanish thing.

They see, I think with great foresight, that this is an international issue and needs to be faced.

Many of them, of these international brigades, come also from Yugoslavia, Russia, many countries.

There are still association of this kind.

For example, regarding the Lincoln column, I think that the archive is in New York. Some of them generate, it’s thousands of people who come here to the civil war.

Some of them are writers that, maybe aren’t in the front line as much as Orwell and Hemmingway, but they leave written some very memorable pages about the war.

Many young fighters, acknowledged photographers. Bobby Cappa runs around here taking photographs too.

There’s an extraordinary mixture with a common element, a great conviction that there’s an universal fight against fascism and there’s also the ideologic feeling of universal fraternity.

It’s an interesting phenomenon, there’s much written about the international brigades. The problem is that, many of them weren’t military, they didn’t know how to fight. They had great losses, it’s cannon fodder that goes to the front line without the needed preparation.

But it was an important support, if you want even real besides the symbolic, to the cause of the republic.