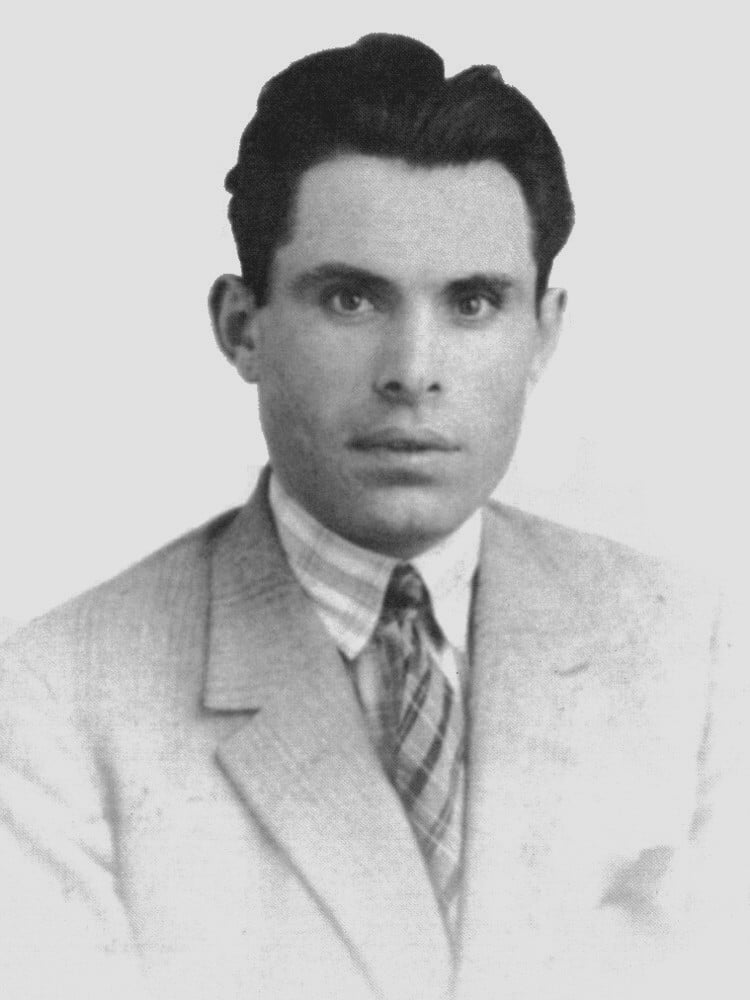

Buenaventura Durruti

Name:

José Buenaventura Durruti Dumange

Roll:

Legendary Anarchist

Born:

1896, León, Spain

Died:

1936, Madrid, Spain

Affiliation:

(FAI) Anarchist Federation of Iberia

Joan Culla Clarà discusses anarchist hero Durruti. Well, it’s not like he was unknown before. He was a shock anarchist from the 20s, the early 20s. By shock I mean an anarchist of action, right? One of those that wore his “pipa”, that is, the gun, always in his pocket and willing to use it and risk his life, to kill or die, right? Well, I think his role in July ‘36 was not, his personal role, wasn’t very decisive. I mean, I think that, actually, that epic idea that’s been shown in movies and books and all sort of places, right? That epic idea, so fantastic, of the military coup in Barcelona being stopped by the people risen in arms, is false. The key factor for the defeat of the military coup the 19thof July ’36 in Barcelona is the behavior of the “Guardia Civil” and the “Guardia de Asalto”, who were the ones who had the weapons and combat experience, right? Because, obviously, to fight with, well, not many, but some 1000 or 1300 rebel soldiers armed with rifles and machine guns, Durruti’s “pipa” wasn’t of much use. Get it? I mean, it was useless. If some anarchist had the idea of, not that I know of any, facing the soldiers with their guns, well, he must have ended like swiss cheese. Because the reach of a gun, a revolver, well, anyway. Then, the key role in the morning-afternoon of that day, was of the “Guardia Civil” and the police at the orders of the Generalitat, who stayed loyal to legality and didn’t partake of the coup. Not only didn’t join, but even fought against it. It was when the military began to surrender -not all at once, bit by bit- that the people began to get a hold of weapons. I mean, the process of arming the people was in parallel with that of disarming the rebel soldiers. The more weapons people had, the less rebel soldiers left. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have been able to get the weapons, is that clear? Then, the image of the people armed in Barcelona is from the 20th, 21st, 2ndof July, not the 19th, Not during the key hours. But, well, anyway they did get weapons. And there were plenty, over 30.000 rifles. Durruti had a role… well, let’s say foreseeable during the fights. Him and other anarchists had, of course, taken to the streets and all. But by the time they begin to be of notice, the coup is for the most part defeated. There are still some spots of resistance, some bastions, some barracks that refuse to surrender. The role taken by Durruti and others, one of the Escaso brothers, is that. Durruti’s role comes, for the most part, later, when he becomes one of the leaders and one of the icons, maybe the strongest icon, of the armed people, of these militiamen, of these revolutionary workers. When Nove… In late October, well, early November ’36 the city of Madrid seems about to fall to the rebels, they decide to send from Barcelona a column of reinforcements to help with the defense of Madrid. Durruti will take the lead of this column, which will later be known as the Durruti column. First, they had been stationed in Aragon. When they saw that the Aragon front was sort of stabilized and there was the need to go to Madrid, they went to Madrid. Durruti died in the Madrid front, and all evidence points to that it was from a bullet shot from their own ranks by accident. But, anyhow, the thing is he died. Of course, the official CNT version was that he had died fighting face to face against fascism. Once dead, is when the mythicizing begins. A funeral procession of thousands of people on the streets, renaming via Laietana as via Durruti, posters, stamps, well, everything. But, as I said, in life he hadn’t been a John Doe, he had been an important figure of this action anarchism. He wasn’t an ideologist, wasn’t a theoretician. There are no books written by him. He was a man of action. But, above all, he was raised to the category of myth posthumously.

Robert Surroca discusses Buenaventura Durruti A long-time anarchist leader. Among those I mentioned earlier. He was a member of FAI, a bank robber, and acted against the ruling class, as well as important businessmen who organized against labor. He spent time in Argentina, where he connected with the libertarians there. He also robbed banks there. He was an idol of the libertarian movement. He formed the Durruti column, and marched to the Aragon Front, and after that, to Madrid. That’s where he died, and it seems to have been the result of the misfiring of his own weapon, not an assault. His funeral in Barcelona was extraordinary. There hadn’t been one of that magnitude since Macià’s death.

Manel Aisa on Buenaventura Durruti Well, Durruti is a symbol for the whole libertarian movement, even though… You’re always told not to create myths or idols, but Durruti remains a myth and idol. Durruti is a Leonese worker who arrives in Barcelona and falls in with every rebel there. For example, with García Oliver. They begin their journey during the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. participating in the heist of the Gijón bank, along with others, among them, Torres Escartín, who was arrested. With Aurelio Fernàndez, and Aurelio Fernàndez’ cousin, too. They do this because Ascaso, Francisco Ascaso, were arrested in Zaragoza, and they needed money to pay for the trial, the legal fees associated with it. They wanted to get them out of Zaragoza. That was why they held up the Bank of Spain in Gijón. Well, he was a legend, later traveling all around Europe. Even America, and the American legend is that he committed robberies all over South America. In Argentina, especially. They connect with many Catalan and Spanish people living there in exile. They manage to leave Argentina after staging a few robberies. The law is onto them when they reach France, though. But they’re not deported to Argentina or Spain. Because, at the time, the Sacco and Vanzetti trial was taking place in the U.S. Sacco and Vanzetti happened around the same time as Durruti and Ascaso. The working class in France is up at arms over the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti in the United States, and the French government is feeling the pressure. Fearful, that they’re destined for a similar fate, they’re deported to Brussels, where they’re exiled a while before returning to Spain after a change in government. That’s Durruti. Then, in 1936, with the famous Durruti Column, he’ll be among the key men defending Barcelona, especially from the shipyard and Plaça de Catalunya. And then, after being shot during the defense of Madrid, the words “Who was Durruti?” begins appearing everywhere.

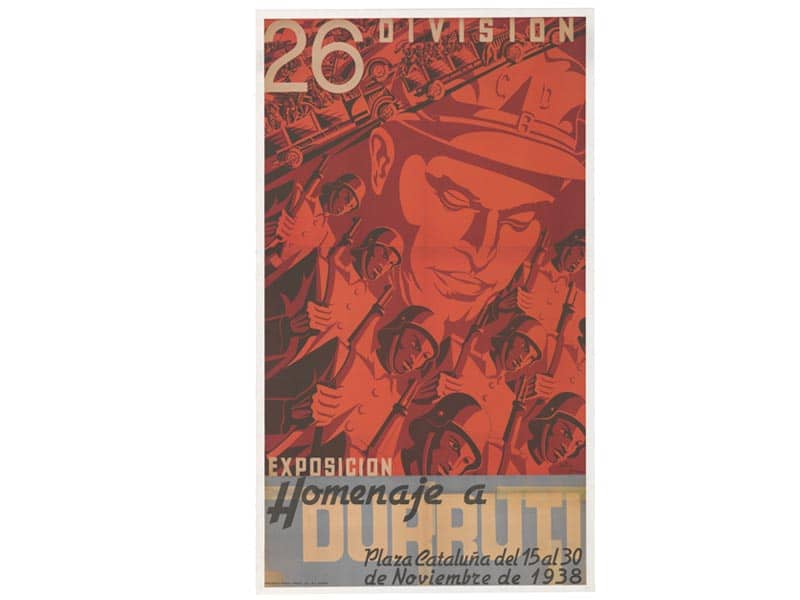

1938 – Poster announcing a tribute to Durruti

1936 – Republican miitia members, in front of CNT FAI headquarters, carry flag and coffin of Durruti.

1937 – Crowd celebrating the unveiling of a plaque that renames Via Laietana Via Durruti.