Ildefons Cerdà

Name:

Ildefons Cerdà i Sunyer

Role:

Urban Planner

Born:

1815, Centelles, Catalonia

Died:

1876, Los Corrales de Buelna, Cantabria

Known for:

Designing the Barcelona “Eixample” neighborhood

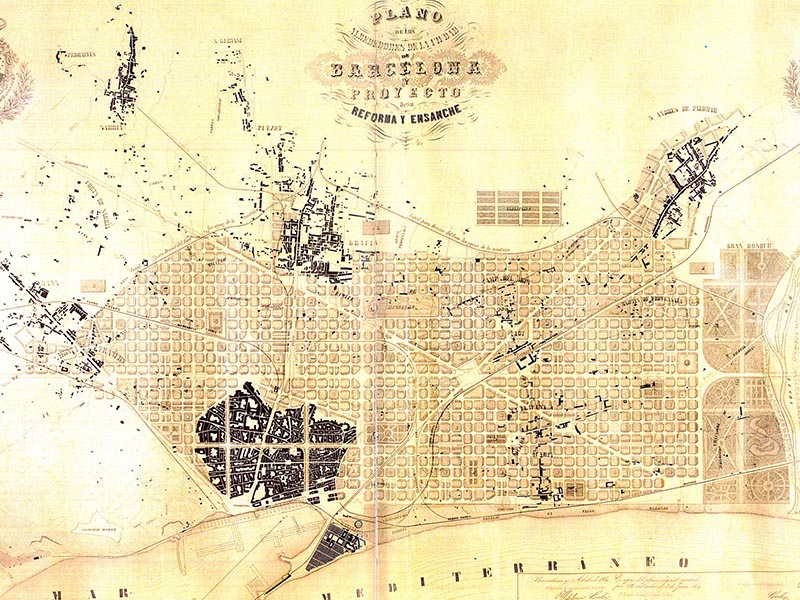

Architect Olga Schmid discusses Cerdà Eixample proposal As always, it is about yield. Cerdà’s plan was groundbreaking. He was an engineer, but his proposal for the Eixample block was spot-on. The block has been studied extensively, and functions well. The chamfers at intersections provide a lot of flexibility. Cerdà proposed two-sided blocks, with a lot of public space for gardens, open to the city. He also played with orientations. To avoid infinite focal points, contiguous blocks turned the facing of the buildings. If that had been carried out, I think we’d have a very different city. A healthier city, with less pollution. All of those inner gardens would have made for higher quality of life. But the yield on those blocks meant that they couldn’t stop building plots. So the plan changed to four sides. That’s the city we have. It’s a proposal that’s afforded much study and research. I think we should have been more careful on height limits. The maximum building height, in the plan, was about four stories. I can’t recall now if that was four including the ground floor or not. If that had remained in force, we’d have more sunshine and better air circulation. But, in the end, speculation plays its role. As soon as more stories and buildings with great height were approved, it eats away at a proposal that was ideal in the moment.

Ramon Alberch discusses the life of Ildefons Cerdà. Idelfons Cera is a man of the first half of the 19th century. He was born in 1815, in Centelles, and died, I believe in 1866 or 1865. He studied engineering, but had, as was common for the time, multiple interests. He was engaged by politics, writing. A man with broad, humanist interests. He breathed life into what would later be referred to as the Cerdà plan, in the sense that he was able to meld the advanced ideas he’d learned in France and Germany with the requirements of Barcelona, owing to the rigid limitations of the [city] wall. His commitment was so great that, although he came from a wealthy family, a family with no economic challenges, he spent most of his inheritance pursuing his cultural and urban-planning initiatives. A man with a complex life, who died, dissatisfied, in 1866, I believe, in a spa, abandoned by his family. A man who lived a punishing, difficult life, in the sense that his ideas were met with great resistance. Perhaps because, for the time, they were novel. In that sense, he was groundbreaking, and paid for it in the manner pioneers often do. The Cerdà plan was seen, in Barcelona, as an imposition [made] by the government in Madrid. The city is encircled, like an old regime, a bound, walled, military city. The housing is unhealthy, with stifling air circulation, a lack of hygiene and poor communication. So they decide, “Well, we must tear down the walls. We must open the city, heed the call of modernity, and create a modern Eixample.” He wins the bid, and in 1860 he is at issue with a faction of city hall, who, along with the aristocracy and bourgeoise, see it as an imposition. On top of that, they dislike the plan because of it’s rationalism: the grids, the inner patios. In Cerda’s own words, “Let’s ruralize the urban.” He had an obsession with accessible art, ventilation, everything the old city lacked. It was, then, a little speculative, pursuing the advantages of an ordered, very rationalist city. Maybe, in a sense, very Parisian. The clashes with the speculative interests of the bourgeoise. Some people thinking that the widening of the walls ought to favor industry, rather than housing. There are also issues within the trade. Architects frowned upon the fact that the project was the brainchild of a city planner. Back then the concept of city planning didn’t exist; he was an engineer. An engineer designs bridges and roads; he doesn’t design cities. That was an undertaking architects reserved for themselves. Yet, the project will succeed, with many difficulties, challenges, but it will be completed. But there’s little help from the city. Much of the time, he’s not even getting paid. As stated, he spent his family fortune. He ended up divorced, his last daughter born out of wedlock, With someone else, and he even acknowledged her. A family like that, for the time, was very difficult. Now it would be seen as more common, but back then, not at all. So he dies without any recognition. Without any assurance that the the project will succeed, because he’s dead five years after the project gets underway. That’s very Catalan, or very human, that a man dies, and isn’t recognized until later. I’ve seen, in the city’s historic archives, the entirety of Cerda’s legacy, the Cerda collection, and it’s an extraordinary work. Even from the perspective of today, it’s a titanic undertaking, with a level of perfection in the drawings. Precision, a thoroughly modern approach. Now he is seen as a leading figure. But he died, I submit, poor, abandoned, and without any sort of recognition.

Gravesite of Ildefons Cerdà in cemetery on Montjuïc in Barcelona.

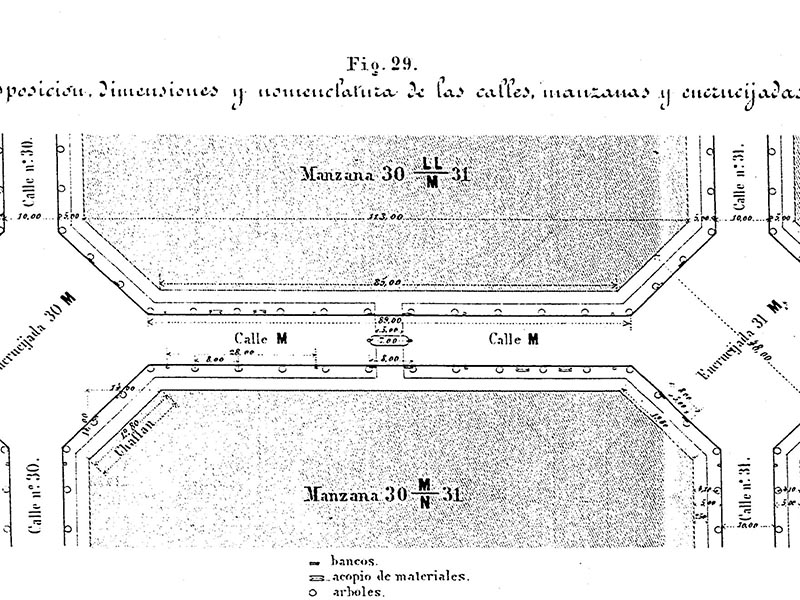

Plans for Ildefons Cerdà Eixample