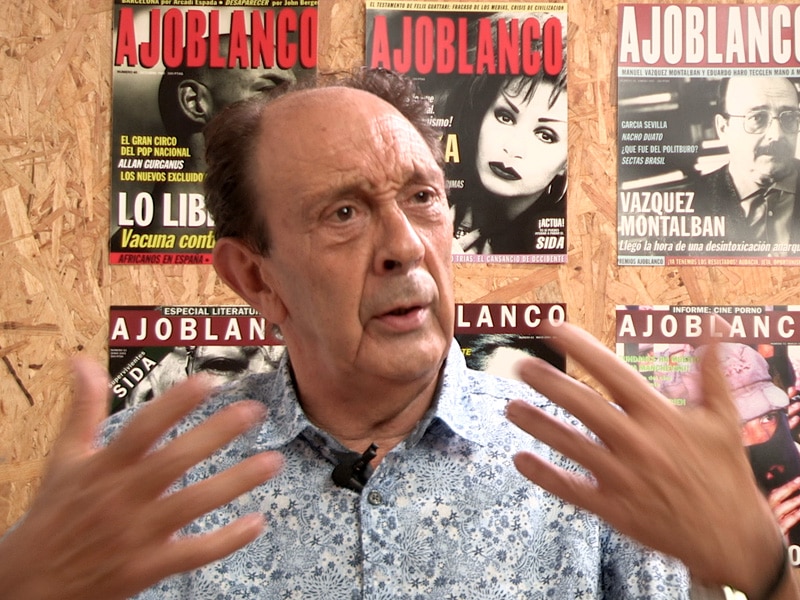

Pepe Ribas

Interviewed July 6, 2017 for Catalunya Barcelona docuseries.

What’s your name and when and where were you born?

Well, I was born late. My parents were already old when I was born. I was the young one, when I was born my father was 50 and my mother 46.

The point is that memory in my family has been slow because my parent married old too, my grandfather didn’t, my great-grandfather did. The interesting thing of having elder parents is that they transmit a history that is much earlier. Because my parents’ youth was the twenties.

That changes many things. I had a very liberal education despite what happened during the war to my family.

I consider myself quite privileged because every Sunday afternoon my father would take me to see landmarks of the history of Catalonia.

For example, I touched the papers of James I, in the archives of the Aragonese crown, when I was nine, ten, eleven years old. I went to the Visigoth churches in Terrassa. We went to the house that had been my grandfather’s.

My grandfather, José Ribas too, like me, was a very important ebony worker in Barcelona, in Spain and in Europe, he was one of the best. And in his store in Catalunya square gathered artists, painters like Casas, Matía, etc.

I lived as a kid in a house full of artworks from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, because my family had this sensibility. This grandfather was killed by a bullet in the train station of Sarrià in April 1909, before the “Semana Tràgica”.

My father was the eldest of five brothers and my grandmother, who belonged to a family that in a way had created all the cotton and electricity industry, the mines and the trains in Llobregat, she had to be a businesswoman because she was deeply in love with my grandfather. He had a huge furniture factory, very sensitive furniture. He also exported to England, Germany, France and the United States.

It’s a history that was lost because my family had always been very discreet. But I lived this as a kid.

Maybe this knowledge, knowing that my great-great-grandfather, for example, was a Carlist who got sent to prison a bag with the head of one of his sons.

Then the exile where my great-granfather became a liberal and an ebony maker and created a great furniture factory in 1850.

He also was close friends with Rius y Taulet and was one of the ones that worked in the 1888 exposition. Then knowing this but without pretensions made me quite special, different.

Different from my friends, with a huge imagination, a great need for freedom and discovering the world by myself and with people that in a way cared more about freedom than ideology, etc.

Because I had seen my great-great-grandfather who was a Carlist on a side, my great-grandfather had been a liberal, my grandfather had been a bohemian, my grandmother a very smart woman , she spoke nine languages.

She was born the 74 I think, 1874, then when she was 34 she had to take care of a very important company. For which she was aesthetically ready, but she had to deal with men and many workers, ebony workers to top it.

In this factory, there was a huge conflict between UGT [Unión General de Trabajadores lit. General Union of Workers] and CNT [Confederación Nacional del Trabajo lit. National Work Confederation] and my father had to throw out the bombs that they threw at one another. Knowing all this history from inside, in a way made me different.

What is your profession?

I’m a libertarian. For example, my grandfather was killed by an anarchist and I’m an anarchist. What I mean is that in my family there’s no resentment, I’ve never been taught hate because it was a humanist family.

So I’ve always had a humanist culture. My parents were readers.

I have made a magazine that I made up when I was 21 and I realized that in university there was Francoism and the ultra-Marxist communists.

Ones as well as the others told us how to think, how to dress, how to act and live. And I said no. I said, “I want to discover it for myself”.

We then organized a poetry exposition in the laws school, which was unthinkable. And the hall, which was immense, got filled with ‘cuartillas’ with poemos, over 250 poets turned up in a law school.

That gave us a moral boost because we realized there was a path to follow. Then the American counterculture books started to appear, specially that of Maria José Ragué, who came from Califronia the 71 to Barcelona and the 72 published a book named “California Trip”. I bought it the 73 and it was a manual of the homosexual liberation movements, the Black Panthers, rock culture, feminism, everything that had happened with the hippie movement and how they had taken it down in a way. And the yippy movement in the democrat convention in Chicago the 69 [Looked it up, I think it’s the 68] where they chose a pig as president of the United States.

All that gave us a motivation boost to dare do what we did. Which is setting up a law magazine during the last years of Francoism. Ad put it in all the kiosks in Spain. And it became the counterculture magazine.

With Francoism it was possible to put Ajoblanco in every kiosk in Spain while underground press in the United States, England and France couldn’t get in the market.

Francoism had, especially during the late years, some voids that were worth filling with bravery, imagination and daring.

What happened with that magazine that we put the first edition in all the kiosks with a mouth and all white? That people saw it strange and we started massing a new generation that wanted to discover liberty by themselves.

Ajoblanco is, deep down, a project in favor of freedom. It was freedom of thought, freedom of debate, of… Culture is what makes you a person, and education is key so that you can know how to assimilate culture.

Now I will mention some historical events and see if you have any story . For example, the 1888 exposition you mentioned before.

Well, my grandfather made several halls. It was very important because it opened Barcelona. Barcelona was a city closed within walls; it was a city with a tiny harbor; it was a city with many insanitariness problems, infections, sewers, etc; very piled up.

A lot of people who had started the industrial revolution in the Maresme, the Llobregat and Reus came to live in Barcelona.

And all that people, right when the walls were breached, and there was an event, organized mainly by a great mayor, Rius y Taulet, to open up the city. And the ‘Ronda Sant Pere’ was made, which is the first street where started to live the people that start to create the industry in this first phase of the industrial revolution.

Which is a much more interesting phase than the second one, so it was through small workshops. After the Napoleonic invasion, there was a grapevine illness, an important phylloxera, and that ended the wine business, which was dominant in the great landowners in the areas of Vic, Besalúc, all that area, Olot, etc.

Then all that people started trading with silk worms, this isn’t told in history books but I’ve seen it in the family archives.

The silk worms were to build silken sails for ships, because the Borbons allowed the Catalans to trade with America. Then the ships that came out of the Maresme or Tarragona had silken sails. The small workshops started producing silk and then cotton.

Cotton in Llobregat why? Because it’s a river that can move the turbines because it’s a river that goes down. The textile industry in Spain was before in Madrid, Sevilla, Valladolid, but from the Llobregat and those turbines, imported from England, they started to generate electricity and to adapt the cotton industry to new technologies, with which Catalans got the lead in cotton. Then came wool, mines, etc.

All that people was becoming rich, so to speak, by marrying among first cousins since there were no banks and needed to focus capital, all that people centralized in Barcelona because the walls were tore down.

This exposition of the 88 is very important because it opens the citadel but specially because all the part of the ‘Eixample’ [lit. broadening] that is around ‘Ronda Sant Pere’ is urbanized. Catalunya square or Gracia promenade didn’t exist yet.

And the mayor Rius y Taulet is very important but since he wasn’t nationalist he isn’t talked about much. But along with Pascual Maragall those are the two greatest mayors Barcelona has had.

Can you tell us more about Rius y Taulet?

Well, I know that the furniture shop and warehouse of my grandfather, José Ribas Fort, was just in front of the town hall in the street ‘Ciutat’ [lit. City] number 5. And there was a fire and Rius y Taulet allowed to get all the furniture out of my grandfather’s factory and put them in the city hall.

There are still many pieces of furniture from my family in the city hall. In the ‘generalitat’ as well, but in the city hall from that fire on.

The rising of anarchism in Barcelona?

The rising of anarchism is, I think, premature. When the workers from Llobregat get illustrated, by learning to write and read, dropping exchange and start using money, through settlements, then there are some social claims.

The fact that they are in settlements inspires a lot of solidarity among them, because they spend many hours together, free time too.

The ‘aplecs’ and the ‘sardana’ come from all this workers that on Sunday would make field trips to the hills and sand, danced, ate, prepared food, kids played, and all this helped inspire solidarity.

And when the employers wouldn’t give in, a budding anarchism started to come to be.

The solidarity atmosphere, fraternity, naturism is very premature and primary, it starts the 1845-48.

They can’t be considered anarchists, but rather they are utopic socialists. They believe firmly in the fraternity of the enlightened. Then many European acrats came, Bakunin, Kropotking, specially in Catalonia because it was a place that was ready for it, because many cooperative companies had been created because of the industrial cooperatives.

Can you tell us about the ‘Setmana tràgica’?

I think it was a social explosion on one side and against the war of Morocco on the other. The compulsory military service, having to go to war to be slaughtered like…

And one thing is working hard but letting yourself be slaughtered like cattle is another. There was a social revolution in a city that had a strong artisan culture. And artisans are guild-like, they are the true artists.

There was a lot of grouping among artisans, which created a solidarity and an indignation against a power growing ever more focused and speculative.

The first industrial revolution we mentioned, the year 88, was an industry that had few banks. Banks appear from the speculation in the ‘Eixample’ and when the slave traders came. Those who had traded with slaves in Cuba and the colonies created a very speculative capital and there was a huge social tension due to this enlightened buy very speculative bourgeoisie.

All of the ‘Eixample’ is actually an operation of speculation. What happens is that the extra money from the industry in Llobregat, Maresme, Reus, Tortosa, etc. instead of being invested in industry and improving the working conditions for workers, is used to speculate in the ‘Eixample’.

Then there’s a social explosion agains this new ruling class that in a way is imposing a financial capitalism, although there is still a strong industry.

The general strike on the 19?

I don’t have any…

The second republic or Primo de Rivera’s rule?

The history of Primo de Rivera was a time of celebration for all that enlightened and speculative bourgeoisie.

Because they completely suppressed the working-class movement he was a manu military dicator. There was a really harsh dictatorship, it was a great time for the bourgeoisie and vert fucket for the working class.

On the 36 there were going to be made some sort of popular Olympic games, do you have any story?

No.

The Italian bombing of Barcelona?

No, my family wasn’t in Barcelona.

The civil war?

About the civil war I have my mother’s story, who did stay. They went to Lleida to get food and during the bombings they hid under the trains.

Then my grandmother had hidden virgins. Then the maids they had walked around with guns, no, what’s the word, not cetmes nor Kalashnikovs; with rifles saying, “One, two, one, two, if we find the virgin we kill her” and anecdotes of that sort.

My grandfather was thrown into prison by the workers of a company he had of graphic arts, my grandfather on my mother’s side, Santponç, and set him free after four or five months so that he could coordinate the work that had been collectivized in the workshop because they didn’t know how to do it, so he did it.

There are anecdotes, but no… I have never been very interested in war, I’m much more interested in peace. It’s a horrible thing war, because it was a war among brothers, a war that tore families or divided the… It was terrible, and besides it there was a libertarian revolution here, not only war. And here we tend to forget that the most important thing was the revolution.

And there was also a counterrevolution in war, it was on the 37 by the communists. Here was Ovseenko, the Stalinist representative, close friend of Stalin, who wreaked havoc here.

It was a very conflictive time because there weren’t two sides, there were three.

And the working people lost. Because Durruti, on the 19thof July, since he was a true libertarian didn’t dare take control and take out all the ‘Esquerra Republicana’ [lit. Republican Left], but he didn’t dare. Who actually won the 19thof July were the anarchists.

The anarchists had got, since the 10, by the police and ruling class, their leaders murdered. Ferrer y Guardia, ‘el Noi del Sucre’ [lit. The Boy of the Sugar], those who were smart and moderate.

And they let the ruling of the CNT-FAI to more violent people. It has to be taken into account that some of the excesses of some libertarians were due to this containment of the working class since 1840.

Then it is logical that there was an outburst. But if you analyze and study the collectivities it’s awesome what the working class managed.

The 23rdof July 36, the Soviet consul, Ovseenko, said to García Oliver, “How is it possible that in Barcelona, three days after the coup, the tramways are already working but in Saint Petersburg it took four years to get the tramway working?” and García Oliver said to him, “We, through the libertarian ‘ateneus’, have been teaching the working class since the 1900, so here there is an enlightened and prepared working class that knows how to do things” and that’s a fact.

Could you explain a bit what Falange was?

Well, I think Falange is a difficult topic because it’s a pre-fascism. It didn’t fully articulate, that’s why they killed Jose Antonio [Primo de Rivera].

It’s very conflictive because it isn’t a closed ideology and it has very socialists components, such as the nationalization of banks and the agrarian revolution.

It was an odd thing. I think Franco used him to have a martyr and be able to do his own authoritarism. But I think that Falange isn’t like Mussolini, it’s more like Mussolini than Hitler. I think it’s not a developed ideology, specially the first one.

It was a countering force against all the chaos that was during the republic. During the republic there were wonderful things but also tough things, as it is logical.

Now it’s very idealized but the republic couldn’t really solve the issues of the country, that’s why a civil war broke out.

Now it all can be changed, but it was a proper civil war, brother against brother, cousin against cousin, it’s a huge thing a civil war.

Could you tell us about what it was like to grow up in Barcelona in the mid XX?

That depends on where you were born. I was lucky to be born in an enlightened atmosphere. When we were young we would do gymkhanas around Barcelona, when we were 14, 15, 16, where we said go to sculpture done by an author, whichever, that is in a park.

So you had to… It was all cultural questions, it was a cultural gymkhana which we did all the time. We filmed a movie when we were 15 all around Barcelona in super 8, we performed theater plays, I organized a rock band that played in nun schools and the nuns screamed.

The priests were all turning communists, we performed theater plays with the nun school besides the priests one, they were Jesuits, the nuns were from the order of the Holy Heart. They all became poor. Then they told you in the spiritual exercises that all rich people were thieves, after inculcating religion in you.

I’ve lived a time that was very… there was Raimon starting to sing in schools, Pi de la Serra came to school, it was a very special time. I belong to a generation, I was born the 51, that was very small but that if you were born in it we lived in a sort of island.

Back then it was a dark city, a city of grey. When you started going to other neighboods, the sides of Barcelona, looks-

We went to the shacks in Montjuïc with the priests to give social aid. Then you had those contradictions, but they helped you grow. It was a contradictory city but you noticed because you traveled too.

For example, when you went to France, you noticed that they had freedom but that the problem was capitalism, not the lack of democracy. Here there was no democracy, in France there was a democracy, but the social injustice was very close.

So you went there knowing what you’d find, because you had read Rorschach [????] and many people, the situationists, from a very young age. Because in school during the PREU, the last year, they gave those readings, so you noticed that the problem was actually consumerism, developmentalism, the Americanism of the ruling class. Because, specially the anglo-saxons, it was a world where they had turned everthing into money, everything into merchandise, everything into exchange and competivity, competivity, competivity instead of fraternity. It is a system and a culture that is rotten by them, who colonized the world in a savage and horrible way. Pure mercantilism.

You noticed that very early in life. It was key in the first Ajoblanco.

In university, could Franco’s regime be felt?

No. In law school, not. It could when the horses came inside with the clubs, but we turned it into a sort of festival.

All the girls going out the windows, some wearing heels and the skirts broke, and we pulled the skirts and felt them up and everyone was laughing. And of course, the cops beating but we always got away.

Some got detained, but usually, for example communists back then, those my age, also became very counterculturals. For example, instead of Marx on the walls they would put Snoopies [??] that said “Students out of the university” instead of police out. My point is, a sense of humor started.

Then, when in a regime the opposition starts with the jokes, the regime is over. I lived a college already… it was some years, 72, 73, that they closed us up all the time.

Of course, there was repression, but Francoism no longer had any accomplices in Barcelona. So you went with Quim Monzón in front of the ‘Palau de la Generalitat’ [lit. generality palace], that was the deputation back then, and you would shout “Samaranch go away!” and you weren’t afraid. We didn’t have fear.

Has there been an event in your life that has taken you to this dedication with cultural activism?

Culture. Reading, thinking, and my father, who I think gave me a very complete humanist education. That’s why I’m a firm believer in education and then living, watching.

Then there’s knowing to pull back in time, so as to have personal time for reflection, not having to be all the time subject to doing, doing. You have to suddenly undo what you have done so that you won’t believe you have the truth. I don’t have the truth, there’s no truth, but there is fraternity.

My compromise is then with fraternity, with the other. The exchange, humanism in a way. And having friends and tending friendships over egoism and what’s mine. Possession is… it’s really a bad thing, wars get started because of possession, that’s mine. No, peace.

Beyond Francoism, Carlism, Monarchism, the class conflict is what’s often considered the root of the issues in Barcelona and Spain in general. Can you talk about this?

Well, it’s an issue of equality of opportunities. That Franco solved creating the middle class, and what Felipe González did was consolidating the Francoist middle class.

It’s what the republic couldn’t solve. To create stability you need a huge middle class that is consumerist, that’s an anglo-saxon invention, but everything is wrong.

You can’t say that this happens in Spain, it happens everywhere. In germany it also happens, but they have a social democracy that gives the worker everything they need to be relaxed and feel safe. The problem is that now all of this is in crisis and insecurity is coming. Now history is being changed a bit.

But actually what Franco did is create a middle class that Felipe Gonzalez consolidated. So it’s the same deep down.

You’ve mentioned that priests were all becoming progresists and so, but did the catholic church have a mayor role during Franco’s dictatorship?

Depending on the time. What I lived is a church falling to pieces. One of the great triumphs of the first Ajoblanco is that we were secular. But that’s because all the priests left, they married. There weren’t priests.

I have lived the disintegration of the church, I haven’t lived the repression of the church. Having attended a Jesuit school, that was the vanguard. And at my place religion was a personal thing.

What they gave you were values, but they didn’t tell you to go to church or about sin, that’s all a non-existent culture. I had very little pressure.

The opposite, I loved the Jesuits because they taught me to love the third world; because they told me about the missionaries in India.

In fact, when I’ve got lost in the Amazon, I’ve always gone with ex-Jesuits. Because they weren’t NGOs.

Something happened to me in Guatemala, in a Jungle, when I met some… What’s the name?

[stop to figure the name out]

In Guatemala I met some Doctors Without Borders that in the first-aid kits, in the ice cubes where the penicillin and important medicines were supposed to go they had vodka.

I then wrote an article where I called them Doctors Without Shame. However, when I went with Intermón [Oxfam] to the Amazon, with Jesuits that had two or three wives and had gone out of the order, they really took me to…

I did many things that were very important with the german greens, trying to get Texaco out of an Ecuador area because they were manipulating a river in which there were some ethnicities that still had the book. But the books isn’t written, the book is what happens in the land, what makes them emigrate or not emigrate.

The residues were destructing the ecosystem that made it possible to maintain the book. I had an intervention, it doesn’t matter, and then the leaders asked me over to visit those lands and I was accompanied by an ex-Jesuit that wasn’t from the Liberation Theology, but the Indigenist Theology.

Those people were suprising. I’ve wandered across many difficult to reach areas of America because of my passion for Latin America. Then I’ve always relied in ex-Jesuits.

So I haven’t had a conflict… What I don’t like, I study, put aside and forget.

About Franco’s death it is often said that it caused both happiness and fear, because of the uncertainty about what was going to happen. What was your reaction and that of your peers when you realized Franco died?

Emotion.

An era was over. Finally a grey world was over and the color came. At least officially, because actually we had been living in another world for a long time.

And then, those who were happy I think was the 30%, not more.

And the other 70%?

It was Francoist, that’s the truth. Because Franco created the middle class, people were thankful. That’s not told, but it’s the truth.

Now it’s changed. That’s why Felipe Gonzalez won, why the transition was easy, because people was already ready, especially in Catalonia and areas where there was more exchange with tourism, more traveling, more access to books, to culture. Culture is always what…

But there were many Francoists. Many people grateful for the sepulchral peace that Francoism imposed.

Can you tell us some more about the way you lived the transition?

The transition is very complex. One thing is what you lived, the other is how you now say you lived it, the important is how we lived it.

Barcelona was a party, until Tarradellas came. I don’t know why, but Tarradellas came when CNT had taken the streets for four months already.

Meeting of Montjuïc, 2ndof June 77, 300,000 people. Felipe Gonzalez’ meeting in Madrid, for the democratic elections of the 77 in June, 50,000 people. Federica and Peirats, 300,00 the 2ndof July.

22ndof July, the ‘Jornades Llibertàries’ begin. Over half a million people debating and discovering freedom.

September 77. Gas stations strike. Barcelona paralyzed by the CNT syndicate that goes around the city in cars deciding who gets gas and who doesn’t. They only give it to firemen, doctors, ambulances, etc. That was unacceptable, so Tarradellas came running.

Then we changed from a social issue to a sentimental one. Then they introduce heroin like they did in the United States with the Black Panthers, they introduce it to Gypsies so that they trade and radicalize.

Keep in mind that back then in Spain there were 800 agents of the CIA. For the United States it was key the future of Spain, specially with Otelo Saraiva de Caravalho in Portugal. The American bases of Rota and Moron are key to maintain the state of Israel.

In the war of Yom Kippur, the 73, Carrero Blanco didn’t let the American planes land out of solidarity with the Arabic world, Spain, Fracoism.

And almost the Israelites lost and the Syrian won. I mean, they landed… Spain is a strategic place because it’s the frontier with another world. That needs to be kept in mind.

Do you remember the day of the signing of the constitution?

Well, no, I don’t remember.

I remember the dossier we wrote against the constitution, but the day of the signing of the constitution…

It was a very bustling time, where feelings were very plural. On a side you were happy, on the other you wanted another constitution, on another side you didn’t want democracy, you wanted the libertarian, on another… We wanted many things at the same time.

I was 24. I had already done klsdjf. 25 years old I was. But I saw that people weren’t ready for what we truly wanted, libertarianism, a direct democracy, But we realized we were very naïve.

What I can is that the moment of greatest freedom in this country was Suarez’ time.

I do believe that he was the best president during tht time. And I believe that he did believe that there was a need to build a democracy. I think Suárez and Carrillo were the ones who believed and that’s why they made an agreement.

I think that agreement was great for the country. I think the nationalists and Felipe González were the ones who put the skids under them. I think they have been evil because they haven’t reformed education, which is basic, and it could be done back then. Now it can’t be done. Now education is Google.

Do you have a story that can serve as an example of life in Spain during the 80s?

That depends. I lived in Madrid and Ldondon. Madrid was a celebration and London was terrible because it was Thatcher, AIDS, the miners, the end of the grants to all basic arts education, I lived in London the 85, in Madrid the 81, 82, 83 and 84.

That was a ‘verbena de la paloma’… A folklore punk. With Alaska, Almodóvar, all of them were friends of mine. But I looked at them surprised, but really…

If you lived in a Fasa factory in Valladolid it was terrible, it greatly depended on where you lived.

Anecdotes… Thousands. I arrived to Madrid the 79. In Madrid there was no freedom. Barcelona in the 73, 72 there was freedom, we did what we wanted. It wasn’t so in Madrid.

In Madrid, when I arrived in September 79, I have always been related to Argentinians because Argentina has a high education level, they are avid readers and there was an interesting exile that helped me a lot during the first Ajoblanco in Barcelona.

So, in Madrid I had many Argentinian friends. I got there, went to the mall with those friends and some ‘Guerrilleros del Cristo Rey’ came in with some chains and split open a doctor’s head. That in Barcelona was unconceivable, and in Madrid it was happening on the 79.

And in January 80 ‘Sol’ [lit. Sun] was opened, a club in Madrid similar to what was the ‘Celeste’ and I remember I saw Alaska play for the first time, her guitar fell to the ground because she couldn’t hold it.

And Núria Amat, a writer friend of mine, and me, who were Catalans, went on stage and started dancing. Then everyone started dancing, but up until then nobody dared to dance.

They were starting to discover reality, we were running away from reality because it had been taken over by heroin. Of course it depended on where you were and who you were with.

Spain is very plural and I know it well. Barcelona itself is very plural. In Barcelona you can live a thousand different worlds and in Spain you can live ten thousand different worlds.

The burning and rebuilding of the Liceu, what makes it so important?

I think it is the change of a social class. Those who first built the Liceu were the industrial and bankers of the end of the XIX century.

Those who burn or rebuild the Liceu are bureaucrats. We have moved from a productive society to a speculative one.

Now Catalonia is nothing, that’s why it’s in decline and why what’s happening is happening, because there’s no industry. No wealth is created, civil servants are created.

And we live off of tourism. Tourism is the first industry and then there are service. When I studied law we all wanted to set up lawyers’ offices, wanted to set up companies, wanted to create wealth.

Now young people can only be a waiter. That’s why we have the politicians we have, uneducated ones.

Now we will talk about Ajoblanco. Could you tell us what Ajoblanco is?

Ajoblanco is many things. It’s a publication that has had three eras. The first was the discovery of life, the discovering of freedom and the Spanish libertarian past. There was a counterculture in North-America, but here there had been a libertarian moevemtn that had made all the counterculture but forty or fifty years before. And it had been the working class, not the students of the most important universities in the world, those with most Nobel prizes. It makes everything very different.

We were fascinated by that. We were fascinated by the libertarian past of Spain, fascinated by what the working class had done in the years 10, 20, 30 of the XX century with their own hands and against everything. That discovery I think was key.

The second Ajoblanco is the world. Other cultures, other musics, musics of the world… And we were the first ones to talk of corruption as a cultural issue. Not only an economical issue, but rather a cultural and social issue. And they told us we were crazy. But you take the Ajoblances and they look like they were written now.

I think Ajoblanco has always been a life school. The social has always been bound to the cultural. Because there’s no culture without freedom or equality. If there’s no equality of chance, culture becomes egoculture, it is egoism then.

It’s a bit why we stopped doing the second Ajoblanco. The second Ajoblance had great intelectuals, great writers. When all those intellectuals and writers started me, me, me and not wanting to talk with the others because I am the one, I am the one, I am the one, we stopped doing Ajoblance because it no longer made any sense. It wasn’t culture, it was a contest, it was market.

And culture isn’t market. Entertainment may be market, but culture is something else, more serious. Culture is what gives you this criteria to defend against what they try to get into you. There isn’t… Actually there isn’t much culture left nowadays.

That’s why we came back in the third era, to try to resurrect a bit the word ‘culture’ dissociated from ideology, because culture has no ideology. You make ideology.

The ideology you have imposed, I mean, what does a teacher or university professor do? Teach or adoctrinate you? Those are very different things. Now most of them addoctrinate. I’m not interested. I’m interested in being taught.

Ajoblanco has been a life school, a magazine that has shaken consciences, has awoken curiosities, has fixed deeds and realizations of people who believe in what they do and do it out of need, because it comes from their insides.

There are people who do things to have a market, but also because they need to do it from inside.

In this third era, I think the world is really lost. I don’t think they will put a chip on us and… If anything that will be the Chinese. I think occidental culture is in a very fucked up moment due to an excess of manipulation, of consumerism. Of create, create, create, products, products, products; and there’s no time to reflect on it and there’s no time for freedom, freedom has no time.

So what we are trying with the third Ajoblanco is to recover a series of values that help people deal with what we have to live but with libertarian dignity. I think that’s it.

What do you think is the difference with other magazines, that has made it so important?

That we don’t have ads. We aren’t market, that’s what.

You’re back after 17 years of pause, why now? What made you come back now?

Coincidences. Finding premises we liked, Fernando retiring, I was taking care of my sister who had cancer, she has been my muse, my friend, my everything, and I came to take care of her to Barcelona.

I haven’t lived in Barcelona those seventeen, sixteen, fifteen years, I’ve lived between Buenos Aires, Berlín and ‘l’Empordà’.

I stopped liking Barcelona, it’s not a city I really want. It’s a city without big exhibitions, everything is controlled by a lying bureaucracy, it doesn’t get along.

Berlin gets along. I’ve lived the whole extention of Berlin and loved it. Because it is my world. Because there’s another way to develop cities. Cities that don’t grow this way, but this way, with lots of green, lots of freedom. You can hold a poetical recital without having to ask for permission, you can make a bonfire in a park for a picnic with your friends and no big deal has happened. Because there’s respect, you go to the subway and there’s no barrier because everyone pays up, because you barely see any policemen, because people are civilized.

Barcelona right now is a touristic city. I don’t… But well, I’m here now so I go along. I try not to be as often as I can, but well.

Which do you think are the greatest challenges of Catalan culture nowadays?

Freedom. It needs to be a free culture. It’s better a good, quality book, it helps more than a hundred thousand subsided books. Subsidy kills Catalan culture, it is too imposed, let it grow free, on its own.

Cultures always grow against and in freedom, not by decree. Catalan culture lacks dialogue, it lacks plurality, it lacks level, it lacks truth. It needs source research, not… All this history that’s being made up is believed by those who want to believe, but it’s a pity, isn’t it?

Because it’s a very interesting culture that in this moment there’s people that’s fighting and publishing good books. It’s a contradictory moment, because there’s also… It’s what we were saying before, everything is very plural.

But that officialized culture, of folklore, all that…

And on a public level it lacks a lot of freedom. On the level of people who are there, believes in it, there’s very valid people, there’s starting to be very valid people.

Those questions are done, but I wanted to ask, where does the name Ajoblanco come from?

From the night of the Ajoblanco. I went to Paris on the summer of the 73, because I went to Amsterdam, to the Golden Park, to see the hippies. And when I was in Paris, in a small park called the Apollinaire, by San Germain des Pres, I had a kind of revelation that was the making the magazine.

So I came back to Barcelona hitchhiking, no, I came back with Ana Castellano, the secretary of Carlos Barral, an important editor. And when I reached Barcelona I summoned friends with whom we had done the poetic exhibition in university, the ‘Nabucos’. We were a poetic group, lovers of Antonio Dartó, Dadá and surrealism and of [Dansapaund].

I convened them to a restaurant where we sometimes went, it was a young woman’s, married to a bullfighter without luck, that was in Putxet. And there also went Rosa Regás, Juan Mercé, etc. The people of the Gauche Divine, and we went to throw stink pellets at them because we considered them elitists.

But we went. And we were the bad ones, the young ones. And the owner of the restaurant, her name was Flora, who was young, very beautiful, from Malaga, the night I told my friends from Nabucos, the poetic group, that we were going to make a magazine, I was going to make a magazine, who wanted in, they all said “All”.

The owner was cooking the typical dish from her hometown, which is a popular soup called Ajoblanco. And it was the night of the Ajoblanco, when we decided to make the magazine.

When we went to the public notary, because since we were law students we did it legal from the beginning, we were a public limited company, we asked our cousins, elder brothers, etc for money. Not much, but well, we formed the public limited company with the public notary of the communists, Ignacio Zavala. He looked a lot like a Quixote, very thin, Castilian, old.

He said, “What about the name?” and I said to him Ajoblanco: it is spicy, scares off witches and always leaves an aftertaste. Prophetic.