EN | CAT | ES

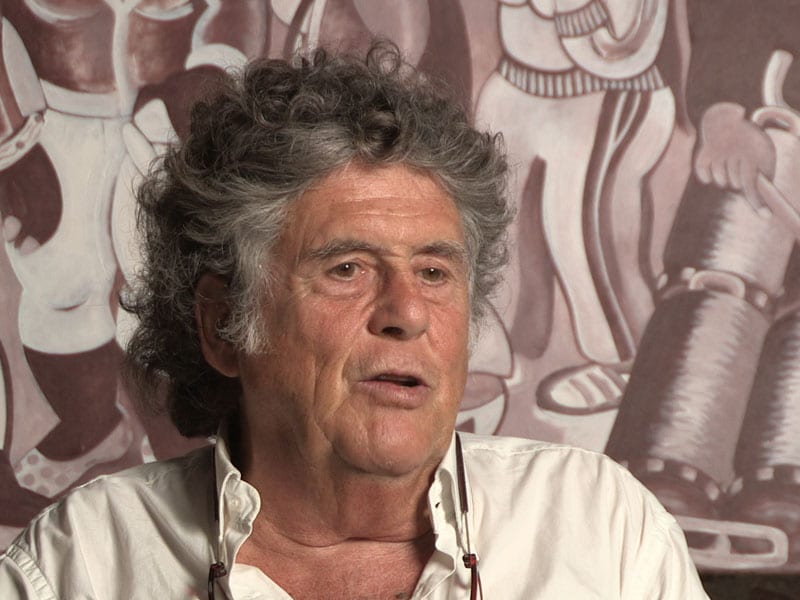

Xefo Guasch

Interviewed May 30, 2017 for Catalunya Barcelona docuseries.

What’s your name?

My name is Xefo Guasch. If you want, I can explain you where Xefo comes from. My name was Josep Guasch, but at school they started calling me Josefo, Josefo, Xefo, and about ten years ago I changed it, which you now can do, and named myself Xefo.

Where and when were you born?

I was born here in Barcelona. I’ve always been a Barcelona person. I was born in Barcelona the 27thof August 1949. And I’ve always lived here in Barcelona, I’ve traveled some but I’ve always lived here.

Do you remember any story that your parents, grandparents or other relations told you about the pastm or some family story?

That would be my grandparents, but my grandma didn’t tell much and neither did my grandpas. My parents did, but it was more about the war of the 36, not the war of the 9.

About the second republic, something?

I don’t know if the second republic was talked much about, but I have to said that my parents have always been very conservative [as in political right wing]. My father died already. They always let us do what we wanted.

My sister, who was a communist, would go hand out leaflets and we would go to demonstrations and everything, but they were conservative. I suppose that they would bad mouth the second republic like they did all republics.

Specially they attacked the republic of Franco’s time, of Franco’s national uprising, but about the second republic, not, and I can’t recall my grandparents either.

Do you have then a story about the civil war?

The civil war, stories… My father was from Sabadell, my mother from Barcelona. From Sabadell, my parent came to live to the building where my mother lived, they met there.

He was in hiding, and they had a chaplain brother who was also deep in hiding. Of course, they always tell you, since they were conservative, that left-wing anarchists persecuted chaplains, progressive [as in left wing people] tell you the other way around.

Here, the Spanish war and the Republic before the 36 was a mess. Specially a mess between anarchists and communists, they couldn’t agree. So conservatives have always talked about “the tragic week and all the mess”, that they killed many chaplains, but it’s not that true.

What was the tragic week?

The tragic week was a week where they burnt… It’s a conservative tag, but the idea is that they burnt many convents, many churches, killed many chaplains. It was actually a burning of… just now I don’t exactly know what it was about.

About your father, you say he was more conservative and Barcelona more anarchist, did he have any trouble or had to hide a lot?

No, and Barcelona wasn’t really that anarchist. There was only the middle-high class, like my parents’. My father was a factory owner in Sabadell, his father had already had a factory in Sabadell.

They were hidden, he always remembers some uncle who had to hide more since he was more conservative. But here there’s always been a very strong bourgeoisie, specially back then.

If you want me to tell you an anecdote, but this is way before, a familiar anecdote. My father’s father, my grandfather, who I didn’t meet because he died very early and my father was the youngest in the family.

I mean my father’s grandfather, had a client to whom he told he had a very pretty daughter and that he’d like to marry her. Then my grandmother would come out to the balcony to see him when ‘the Guasch’ passed through, they called him ‘the Guasch’, didn’t want them to tell her his name.

She saw him pass and ended up marrying him. They had four children. She didn’t give him money, but hid it where he knew and he’d head to Barcelona to drink. It’s just two generations before me.

And when he died, she would always tell how rested she was: “My husband died and I was so at peace”. And that was two generations ago.

Can you tell me something about the bombing of Barcelona by Italy?

All this I know from reference, I wasn’t even there. My parents remembered the bombing, but didn’t talk much about it.

Wait, start the sentence.

The bombing of Barcelona during the war wasn’t talked about often. My parents didn’t talk much about it because they were conservatives. They did hide, but during Franco’s regime you didn’t talk neither about the bombing of Barcelona by Mussolini and the Italians nor about the bombing of Guernica by the Germans and the Nazis. It wasn’t talked about much, but you find out.

The moment they bombed here in Barcelona, there were many people who wanted to escape by ship, they later went towards Valencia and took the chance to bomb.

The first experiment was Guernica, in the Basque country. It was the first bombing of a civilian population by the military air force, they killed everyone. Here they did a bit that and people got really scared. But here they already had some refuges ready, that can be visited, and people would hide there. It was quite intense, yeah.

And some story or anecdote about the civil war?

I can tell you about these refuges I told you about before. I’m an architect and I once made a building here in Barcelona. We started digging the foundations. The first day we got there, there were a lot of neighbors demonstrating there.

They said there was a refuge there. But we started the work and couldn’t see the refuge there. Then we dug for the foundations. The first day that the concrete came, they poured it and it disappeared.

It turned out that doing the foundations we had burst the refuge. The entrance to the refuge was a trapdoor that must had been in a pharmacy, so nobody had gone in for a long time.

But after a few days someone from the town hall came with pictures of the concrete inside the anti-aerial refuge, and told us we had to get it out, which was very difficult. And it was never spoken about again. Nothing happened, but there’s a refuge there, there are many refuges in Barcelona.

And a story about your parents regarding the civil war or something?

About the civil war they did tell me stories, specially about chaplains and nuns they had in the family and they had to hide. About the uncle who was the most conservative, who had to go to San Sebastian. Many rich people left for San Sebastian on holidays while here war was being waged.

They always say, “War was very tough here”. It was “very tough” but many of these were on holidays. More anecdotes…

Well, there’s the one that my father came to live here from Sabadell and went to live to the building where my mother was. He didn’t know her and met there and got involved. That’s a curious anecdote.

About love, right?

He was hidden, I think. She wasn’t.

How was growing up in Barcelona in the middle of the 20thcentury?

Well, living in Barcelona in the middle of the 20thcentury is living in the postwar Barcelona. As a kid you don’t realize much, there weren’t many freedoms but you don’t realize.

As an anecdote, I can tell that my father always had a notebook and gave us money for setting up the table, making our beds, and stuff. He was very Catalan and gave us money for speaking Catalan.

But then, when Franco died and Catalan started to be spoken and pressed for, he would get angry with newspapers or people that used Catalan. And we would tell him, but five years about you gave us money to speak in Catalan. But then he had the notebook and took note of it.

As a kid, it was really neat. Then there were the schools, I was upper-middle class so I went to really good schools. Those who had money lived very well. We would go to the mountains for summer and all.

When you start growing up and start thinking more and see there are few magazines. We went to watch Cinema at Céret, right besides Perpignan, France, where they made cinema weekends. We would go there and watch four movies each day.

If it was two days you could see eight or ten movies, but if it was three days you came back here trying to remember if the black and white one was the erotic one or the warfare one. There were no movies here, magazines and books were also brought from Paris, bought at Perpignan. Always outside.

And it was all illegal? Could you buy the books and magazines?

No, these books were illegal, completely illegal. What you studied here, the history we were always told was that Franco was the “Good guy who crushed some evil people”.

But of course, when you start seeing that was Franco has done is a military coup, that he has come with the moors, jumped into the peninsula and taken down what he could, you realize that it’s the exact opposite of what you’ve been told.

Both the textbooks and the schools told you the other history. There were some progressive schools, but it wasn’t mine.

Beyond Francoism, monarchy and Carlism, in Spain, and specially Barcelona, there was this social class difference between the bourgeoise and poorer people. Can you tell something you remember about this conflict between bourgeoise and the working class?

The difference between bourgeoise and the working class in that time. The bourgeoise was very strong and there were many shack areas here in Barcelona. Just here, where there’s the Vil·la Olímpica [Olimpic Village] that is all beaches, there were all the shacks of the ‘somorrostro’. In Montjuïc there were shacks as well.

There were many shacks areas, there were lots of very poor people. Country people, who like now had no money came here, but didn’t find much work here either. Despite everything, things started to get constructed and an evolution began.

Anecdotes I can tell… I went to a bourgeoise school, the ‘Salle Bonanova’ “of the brothers”, some people who managed it who weren’t chaplains or anything but dressed up as chaplains.

They had a small building that was the free one, you didn’t have to pay to attend. But we went with robes with squares of some colors and those from the free one other colors. It was great because they allowed them to study there, but they made them dress up differently so you would realize who they were.

Since after the war a lot was being constructed, there was work. Poor people kept being poor, actually, but they slowly prospered.

Did you say something about the we are pink?

Somorrostro.

What’s that?

“Somorrostro” was a shack neighborhood, a whole area of shacks that was… Now we are in “Poble Nou” [lit. New Town] that was a neighborhood of factories, lots of factories. Then there was the train tracks, and between the factories and the train tracks, and the beach, there was a whole neighborhood of shacks.

There were lots of gipsies. “La Chunga” [lit. the tough/dangerous woman], Lola Flores, all started here too. All those gypsies here danced a lot.

Then, when I was older, here is where there were drugs, they had marihuana. The Gypsies had it, in Barcelona it was much more difficult.

It all disappeared before the Olympic Games, but not so long ago. It disappeared around the seventies or eighties, and there it was later built the “Vil·la Olímpica”. The beaches were fixed, the sewage from Barcelona poured the water really close to the sea and it was sickening. They built some sewage collection tanks that poured the dirty water further away and they fixed the beaches.

Now, when people come here and you tell them that there were no beaches before the 92, they are stunned. You couldn’t swim, there was no beach and the water was really dirty.

All this comes from the Olympic games, right?

For the Olympic games, they tore down lots of factories, some really beautiful. There were some protests, “They are tearing down everything here”.

They took out the train, tore down some factories, removed the shacks and built the “Vil·la Olímpica”, which was where the athlete lived during the Olympic games. Later it has been showed as a modern neighborhood since the year 92, when the beaches were fixed and all.

Before, just by the Barceloneta, there were some restaurants where you’d go eat paella and stuff, it was lots of fun. You’d eat on the sand, the tables were on the sand, your feet on the sand. When they said they were tearing them down, there was some citizen protest, but they did some cleaning and it turned out really good.

[pause]

During Franco’s regime, I do have a story to tell you. We were three brothers that followed up close, and then two more way younger.

But my older sister was a convinced communist. She would keep under her mattress leaflets, sprays. She got up in the morning, went to demonstrations in factories, handed out leaflets, sprays.

I already told you my father was very conservative; my mother was conservative but not as much. My father was very conservative but allowed us to do what we wanted.

We had a cousin in the fifth floor who was close friends with my sister. We lived in the first floor.

When the cops came after my sister because she had done something, she would go live in the fifth floor, at the house of the others. And when they knew that Teresin, the girl on the fifth floor, was being chased, Teresin lived at our place.

Then, these leaflets. My sister married a university teacher, a convinced communist as well. And when they went to live together, they married, took a place, when she left to live in the other flat she left behind the leaflets, the sprays, the [octavillas] and everything under the matress. My father told here: “No, now that you’re married and have a home, you have to take everything”. But here never got angry or told her anything.

What do you think about Franco as a person and a dictator.

I think that Franco… Franco was a short, chubby man, not a big thing. So Franco was in the north of Africa with the legion and everything and got support from here so that he would rebel. They got him a plane to rebel against the republic, a democratically chosen republic.

They got him a plane and he flew to the peninsula. First everyone thought nothing would happen, but he kept on conquering. People signed up with him, in ever bigger amounts and he kept crushing the republic. It was a bit out of control, they didn’t have many weapons or anything.

Franco got weapons and economic support. One of the many that supported Franco a lot were the March, the big rich Spanish family. They have lands in Mallorca, they have sons, they have the March bank. Those practiced what’s known as ‘estraperlo’, they took things here and sold them. Bringing materials or objects from the outside and sell them here. They made a lot of money with this. And with weapons, buying and selling weapons.

The supported Franco economically so he always had the coin and people kept signing up. All the story about Franco was a bit nothing.

Her wife was more a harpy, they called her ‘la collares’ [the necklaces]. She was wearing lots of necklaces, but wasn’t either… Franco was a rather small thing.

It wasn’t like Mussolini, who had and incredible cult of personality. Mussolini, wearing boots and a military outfit. Franco with the Spanish military outfit and the medals was quite embarrassing.

He wasn’t a Hitler either, or a Stalin or anything. Frnaco just lived, nobody killed him. He died in bed because he wasn’t much of a thing.

But he was a dictator and went his own way. But specially, as with many people we had, the worse were Franco’s inner circle. The ultra right wing, ‘Alianza Popular’ [lit. Popular Aliance], the conservatives.

When you read about Franco’s death, you read two things: that there was fear and that there was happiness.

Well, not much fear.

Fear was especially because of the uncertainty of what was going to happen. What was your reaction and that of those around you when you found out he died in the 75?

Well, Franco’s death was soft for him, because he was dying for a year, with his brother-in-law taking care of him. They had him there and never ended up dying.

But in Spain it had been for a while as if the dictatorship was ending. In the world there was the May of the 68 in Paris, the hippies and the revolution in California, so at the end of the 60s it was already like the youth revolutionary movement.

Then at the beginning of the 70s Franco, who wasn’t doing much already, left and movies, books and culture started to get in. People really felt like doing a lot of things, the older ones did the ‘caputxinada’, by which many ended up in prison.

But it was over in two days. Vazquez montalban, writers, all these were a bit older than we were, but Franco’s stuff was ending.

In the 74, 75, when Franco died, everyone took the streets with bottles of champagne to cheer. Nobody thought anything was going to happen. There was always the doubt that maybe the army would go out and something would happen, but it was one of those long deaths that I think they couldn’t take it anymore – and specially us, those who were against Franco.

So we had to celebrate the freeing of the country. But as I told you, for a year or two it was quite freed. The country was freed and a lot of stuff started to come in. All the movies and everything came in, it was a total euphoria.

What happened during the transition period, between Franco’s death and the sign of the constitution the 78? What did you and your friends talk about and what was talked about in public places?

During these years, between the 75 and the 78, those who were already into politics got deeper into it. The socialist party and the communist party were legalized. Parties that were completely forbidden were legalized. Carrillo entered Spain with a wig and after a while it was legal.

I wasn’t much into politics. Well, I had a video group we formed around the year 77. We filmed the first elections, rented a bus and filmed the first meeting of Felipe Gonzale, who was really young, in Montjuïnc, the straight lane in Montjuïc with a huge screen. Felipe Gonzalez holding a meeting, that must have been the 77 too.

Of course, we filmed that and a lot of people and found it normal. And specially what I said before: cinema was coming in, movies were coming in, cartoon magazines, that messed with everything, started to get published. Intelectual magazines, like ‘Triunfo’ [lit. Triumph]. More alternative magazines, like ‘Ajoblanco’. Music magazines, that also started then. And since there was no movement against it, it all went smooth.

Transition is now quite controversial, but it went along smoothly, everyone had its say. We had a great transition that was an example for the world, to go from a dictatorship to a democracy without anything bad happening was great.

And for us it meant a lot of happiness, being able to travel, to get outside and in the country. People from outside came in, contact with the outside world before Franco’s death meant the few tourists that came here and few people who could go out. Suddenly everyone could go out, it was a total opening.

Do you remember the constitution day as something special or memorable?

I suppose so, the day the constitution was signed I suppose it was a special day. But not like the day Franco’s died that we remember often, everyone going to ‘La Rambla’ and so. I don’t specially remember the day of the signing of the constitution, but like I said before the constitution came along smoothly, there weren’t many problems.

Regarding the constitution there’s also… left wing parties, the progressists like Podemos or the socialists, who want to change the constitution. But it’s been there for forty years and nothing has happened.

But it’s also a constitution that was made a bit between a rock and a hard place. There were the communists, the socialists, and then all the right-wing parties that are still in the ‘Partido Popular’ [lit. popular party] where there are still many Franco supporters.

These are now pressing, but I think it was a huge step. The Spanish transition and constitution were great.

If you want to add something, no problem.

Those years, between the 70 and the 75 were really felt here, in Spain and specially Catalonia and Barcelona, in the anarchist party, the CNT.

The CNT was a really strong movement. As a video recorder and as a photographer, back then I was a photographer and filmed videos, I followed them around a lot. Then there’s an anecdote too, I went to live in a flat in Medinaceli square where the CNT had had a huge flat.

They had many flats, controlled the cinema syndicate. I followed them during the gas stops strike that lasted for 10 days, it was really harsh.

All these ended a bit, the CNT as well I think, I used to follow them before Franco’s death, when the ‘Jornades Llibertaries’ [lit. libertarian days] were held here in Barcelona. It lasted for four days and took place in the Güell park. It was organized by young people who were affiliated with the CNT but not deep in it.

During the mornings, in the Diana hall, meetings were held with members of the CNT from all over Spain, even some from foreign places, Cohn-Bendit came to give a speech, they talked. We filmed it and showed it at the Güell park.

But the Güell park was chaos. The whole park taken over by young people, drugs, sex. During the night, there was a stage where there were concerts by ‘Ocanya’, ‘el Camilo’, those were really famous back then, Lazario dancing naked on stage. Then people all over the park well, having sex and smoking weed.

This wasn’t really along the lines of the CNT, anarchists have always been very serious deep down, and they were a bit shocked by all that sex, drugs and rock’n’roll.

I think that’s where the classical CNT went down and anarchism rose, but an anarchism with no flags.

You say you were a photographer following them back then and so, do you have any story?

Those were the years of the ‘grises’ [lit. grey ones]. I studied architecture, I’m an architect. I studied architecture and it was a bit hard in universities, there was a year that there were almost no classes. And another year that you always had a grey clad man, who was a national cop, in each classroom.

The year we had no clases, classes would start, but then the ‘grises’ came and starting hitting people and we the ‘grises’ as well.

Then with my sister, who was a convinced communist. I was more anarchist. There were demonstrations on the streets quite often. You’d go there, the ‘grises’ would came and bam, bam, bam, handing out smacks.

As a sort of strong and dangerous anecdotes, I got beat up a couple of times during demonstrations. But during the ‘Jornades Llibertàries¡, I was filming in the Diana hall. The Diana hall was a theatre that had been an old cinema, a theatre where quite progressive plays were performed, the managers were quite anarchists and organized the meetings.

We were there filming and suddenly the ‘grises’ come into the theater. It was full of people and we just filmed them, we kept filming. It all calmed down, I don’t really know why, but they were inside. Everything just calmed down and the meetings continued.

And other dangerous stuff, I remember anecdotes if you want them. We had a kind of flat and office in front of the police station in Laietana way. Right beside it was the ‘Palau de la Música’ [lit. Music Palace] where the first concerts were performed.

With some friends, a day where there was a concert, we had smoked a lot of weed, were high and had to pass in front of the that police station. In front of the station there was a lot of people demonstrating and singing. We thought, damn, people going against the cops. We got in the middle, and suddenly they rose their arms and started singing the ‘Cara al Sol’ [lit. Face to the sun].

We then realized they were complete right-wing fascists defending what was going inside. We just ran out of there and went to the concert. But we could have got beaten up badly there.

You’d find a demonstration and wouldn’t know if it was in favor or against. We thought that one was against and it turned out to be in favor. We went out and nobody said anything to us.

You need to think that americans don’t know much about ‘grises’ and ‘rojos’.

These ‘grises’ I’m talking about attacked all universities. Of course, when Franco died suddenly and everything was freed there was a lot of movement against, it was where all the students were.

The ‘grises’ wore grey clothes and a helmet and drove in vans called ‘Gris’. These vans were called ‘yogurteras’ [lit. yoghourt making machines]. ‘Yogurteras’ comes from yogurt, which is basically curdled milk. They had a very bad character this ‘grises’ that came to deliver, “Hey, the ‘yogurteras’ are coming”. So you’d go inside or if you were demonstrating you’d take the streets.

The university movement I understand that it was quite strong against Franco’s regime.

The university movement… The university was where the planting field was. The workers did their own thing, but workers have always been a bit more caught up since they can be fired.

Students, since they are students, if they close it up, it’s closed up and don’t… Workers did a lot of demonstrations. In the ones in the Street the students and workers would get together, they were quite intense.

Despite everything, a workers’ demonstration, of a whole Factory, is a lot of people and stronger than a student one.

But yeah, the ‘grises’ dealt out a lot of… Many people were arrested, put in the Laietana way and they had them in there for a few days, they beat him up to see what they could get from them.

But it was everything a bit… The dictator was already dead, what I’m telling you, maybe even before his death. But about the years before Franco died and those after, approximately.

Even before Franco’s death, the ‘grises’ beat up. But not as much, they were always around.

As an anecdote I remember, now that it’s been the birthday of Raimon, a Valencian singer, that was somewhat forbidden. I remember a concert in the ‘Palau de deports’ [Lit. Sports Palace], where he sang a song named ‘Diguem no’ [lit. let’s say no].

He was forbidden to say “Let’s say no” and another one about guns, so with the whole ‘Palau dels Esports’ full he would say “Let’s say” and all the public said “No!”, “We don’t believe in” “Guns!”

But rumors started to spread that the ‘grises’ started to arrive outsid Then the ‘Palau dels Esports’ was surrounded by ‘grises’ and all this mess inside. But when it was over, we all went out and nothing happened.

Another concert that was sort of troublesome, in this one some rubber bullets did fall inside, was in the bullfighting ring for the Rolling Stones concert.

I don’t know what else happened those days, I think there was a murder by the Francoist regime, and the ‘grises’ surrounded the bullfighting ring.

Those who were left outside, because some people couldn’t come in, started to demonstrate and outside there were a lot of hits. From inside you could hear that outside there were hits, but inside the Rolling Stones were playing.

When it was over nothing happened, but during the concert some smoke bombs and rubber bullets did fall inside the bullfighting ring.

Were you ever in prison?

No, never. It’s something I’ve never experienced which isn’t a bad thing. But then… It’s good to have the experience of being sometime in prison and see how they treat you, but I’ve never been myself. It’s always been a close shot.

The relationship between the catholic church and the city has been, historically, difficult. Can you talk about some conflict with the church in the past or now?

The catholic church has always been very strong in Spain because it supported Franco. The same in Barcelona, it was always strong in Barcelona. My parents, who I mentioned were very conservative, were also firm believers.

My father attended mass daily, he always told those who didn’t go that he prayed for us. The catholic movement was always strong here, there was the visit of the Pope and all.

But at the same time here there were the monks of Montserrat, that have always been against Franco and his regime. They have always supported and defended the lefts.

There was also the ‘caputxinada’, from the ‘caputxin’ monks. They once let their halls for a reunion where there were architects, the generation 5 to 10 years older than me, architects, philosophers, all gathered there. And the police came and surrounded the convent, there in Pedralbes.

They surrounded it all and had to stay inside. They spent a couple of nights and then took everyone and put them in jail.

The people who were there always remember that time as great. Some got beat up, but all the intellectuals and not so intellectuals, but writers, journalists, architects, all the progressive people went to prison together in cells. They remember it as a great thing.

And when it comes to Francoism, the ‘caputxinada’ is an important movement.

But what was exactly that, why did they gather there?

Damn, I can’t either, my memory is horrible.

I didn’t know, that’s why I asked.

The ‘caputxinada’ got there together to write a manifesto against Franco. I don’t remember what year it was now, if Franco was there or not. I think he was still alive.

The intellectuals gathered there to write a manifesto, publish it and everything. Since there were rather known people in the ‘caputxinada’, well the ‘caputxin’ convent, they were all known, the cops went there, surrounded them and had them in there for two days.

The ‘caputxins’ always took good care of them, they’ve always been very defended. That’s a bit between the catholic catholics and catholic chaplains, the catholic bishops lately have been more progressive. But there have been very conservative bishops, they’ve always been wholly in favor of Franco.

The ‘caputxins’, the monks of Montserrat and all those have always defended the more progressive part.

We can write down the ‘caputxinada’ down and check it out later.

What was the answer of Barcelona when Antonio Tejero attempted the coup in the ‘Corts’ with the army and all?

The 20N is when the ‘lieutenant colonel Tejero’ invaded the congress. They were together voting to choose the new president who I don’t know which one was going to be, maybe Suarez.

They had to choose Suarez. The president in that moment – my memory is the worst – had been a francoist and did well, he took care of the transition.

Tejero invaded the congress, fired some shots. The television cameras that were in that moment were left on, they pretended and left them on, it’s all recorded.

Of course, everyone was quite shocked, what’s going on here? Outside, they surrounded the congress and didn’t let anyone out. I also need to say that when Tejero came in and started firing shots, everyone threw themselves to the floor except Fernández Miranda, who was the president, and Adolfo Suárez, who was to be chosen.

All the other ones were scared out of their wits, because it was a moment that Franco had died a year ago and everyone was thinking, well, here comes the army.

It was a coup… Seen from the outside, now I’m writing a book of my times, ‘Recordant Temps’ [lit. remembering times] and I thought, I was writing that the other day, that was a huge shock.

In Valencia, other lieutenant colonels took out the tanks to the street. At the same time we were getting images of Valencia with the tanks on the street, Tejero had invaded the Congress with all the congressists and had it surrounded. Damn, it could be very hard.

But you could also see that it was quite botched. A botched job si something that’s not quite clear. It was never clear who was in charge and organized all of it, that’s still not clear.

But from the outside, what I said I just wrote now in a book, I remember it as something really surprising but not to get scared and stay hidden in home, rather to take the streets and start shouting against it.

And nothing happened. It was all over, it will someday come to light how, with a speech from the king Juan Carlos, who gave a speech.

He was the chief of the army and gave a speech that it was all over and it had been stopped. Apparently the military who didn’t rebel obeyed him and the common people were also at ease.

But it was something very shocking, but not that dangerous.

Do you remember the terrorist attempt in the Hipercor mall the 87?

The terrorist attack on Hipercor, that’s a big leap there. That must have been the 87, I think you said. I think ETA was quite messed by then.

ETA started great. We all supported ETA, the first they killed is a cop called Manzano who was the great torturer in the basque country as well as here. And they killed him, it was like this ETA guys are quite well, very progressive.

Then the admiral, the great admiral Carrero Blanco who was set to succeed Franco. They placed a bomb when he was passing and the car flew up three stories and fell on top of a building.

This one was worse than Franco, he was going to succeed him. They killed him, everyone said they’re nice in ETA.

But ETA started to get messed. All the armed revolutionary movements when you start killing get messed up. That’s always happened, both on righ-wing and left-wing movements.

ETA had been getting messier for a few years and putting bombs in ‘Guardia Civil’[lit. Civil Guard] barracks. As a concept you think, if you want to kill ‘Guardia Civiles’… But they killed the ‘Guardiaciviles’, the wives, the sons and whoever passed there.

So here in the Hipercor they put a bomb in the parking and killed a lot of people. That meant a lot the ending of ETA, of the support from the common people and they started with the internal struggle, because they went too far there.

Regarding this, the five bomb cars that were put the two last years, how did it change the way Barcelona looked at ETA?

ETA, as I said before, had been getting messed for a while, placing bomb cars. Bomb cars kill whoever passes through. You can always say that you were trying to kill whoever, but you kill the first person to pass through.

They put several bomb cars in ‘Guarda Civil’ barracks. ‘Guarda Civil’ house barracks. In house barracks lives the ‘guardacivil’ with their whole family. Depending on what time you put it you will kill more women and children than ‘guardiaciviles’, because they can be out working. If you put it during night, everyone is sleeping so you kill them all.

That’s the time they got messed. The leaders of ETA got a bit stubborn, had quite internal strife and tried to make a strong movement.

They could see that their history was ending, it’s still a bit around, but they saw it was getting over so they pushed their hardest. They pushed and I think that for the it was the final descent.

We’ve talked before that there were many gypsies here, but how have the Gypsies influenced the Catalan culture?

Gypsies with the Catalan culture… Well, Gypsies are from the start a rather free people, they live their own way.

They’ve always done their own thing, even during Franco’s time. But they lived in shacks, always poorly. But they’ve always been free and left to their own devices.

The thing around the end, before Franco, some strong characters started to appear. Lola Flores, ‘la Chunga’, here in Catalonia.

The real gypsies, the true flamenco ones, were actually in Andalusia, Morón and Sevilla, Cadis…

But here in the ‘somorrostro’ a strong movement started. Many years later, I don’t know if it’s related with that, came out the ‘rumba catalana’ a more easy to dance flamenco.

It was a time, around the eighties, where we had the ‘Celeste’, the ‘Gato Pérez’, it started to whole ‘rumba catalan’ movement. Now it seems that it’s going to come back, it went off for a while, but now they’re trying to bring it back on.

It was a very strong movement the ‘rumba catalana’. It comes from the flamenco, but I’m not sure if it’s the flamenco from that time in the ‘somorrostro’.

El Quimet, el Xiquet li diuen a aquest?

What?

Now they are doing a movie about a kid, well , it’s being made by a friend of mine, Carles Bosch, a friend of mine handles the public relationships, about a flamenco from around the ‘Raval’ who wants to perform in the ‘Liceu’.

But is it a kid?

It’s a big guy, no, a fatty that’s called ‘Xiquet’ [lit. Kid], I’ll try to remember later.

Can you talk about the shack neighborhoods in Carmel, what that phenomenon is? They started to exist in the XIX century but the government acted quite strong against them in the fifties and sixties.

The Carmel… Shack neighborhoods here in Barcelona there were many, there was the ‘somorrostro’, the one in Montjuïc, the one of the Carmel.

It was mostly emigrant people, who had nowhere to go and built shacks. This is what happens everywhere in the world except with the emigrants now that don’t let them settle anywhere, they have them in tents in the Greek Islands in tents. But before they made their own tents.

The Carmel I don’t know exactly how it was. There was a time when Franco tried to clean up everything, that they weren’t seen specially, that happened everywhere.

I don’t know if it was because the Pope was coming for the eucharistic congress, like they’ve done in Brazil with the Olympic games, that they’ve hidden them a bit.

What pushed you to arts? Is there any tradition in your family?

Art for me has always been important. There’s no tradition in my family because my father was a fabric manufacturer.

As an anecdote, I could tell that my mother painted great, draw great when she was eighteen or nineteen until she got married and stopped drawing. Now that she’s ninety, she sometimes draws.

But that was the typical marriage, you were a young girl, painted, she did it great, but got married and never did it again.

With art, I’ve always had many friends in arts, I’ve always followed art. Being an architect is already quite the artistic job, but having worked as a photographer, filming video, I even perform theater, pain, sculpt. Seven years ago, I enrolled for sculpture learning in Massana.

Now I’ve put up a gallery so that people who does art can…

Art is something that I’ve always been interested in. I studied architercture, that already is an artistical practice, but when I was doing architecture I already worked as a photographer, then I started making video at the same time that I studied architecture and then I worked as an architect.

Most of my friends are artists, I’ve always had interest in what artists did. About seven years ago I enrolled in the Massana school of sculpture. I went with Maria Alguera, a friend, I’ve painted for five years, with Gabriel, who is a sculptor, I’ve gone paint with him several years.

Lately, instead of painting what I do is rub the fabrics. And I ended up setting up a gallery at my place so that people who can’t expose can. It’s not much art, but at least I can expose it.

What else can I tell you about art? It’s the only job that you supposedly don’t do for a reason, but rather because you like and it comes from inside you.

Is the side of everyone that has to be explored and brought out…

Yes, now I am waiting, which I had never done before.

It’s art as well.

As an architect I haven’t worked much, I had an office in Ibiza, one in Formentera and also an office here.

Since I’ve done a lot of things, that’s the only thing I regret from my life, I think, having worked little as an architect, because I also think I was really good.

But I haven’t worked much because I’ve been doing other things. Among those things I’ve done is setting up restaurants and handling them and handling clubs. I have a rather big night life history. It is what I’m reading a book about now, the Barcelonese night in the 80s, it was a very important moment.

I went out at night, set up locals, what I liked was setting them up; during the day I was an architect and earned money as a photographer. Maybe it is the most fun and alternative has been the video, it was video in neighborhoods, community videos.

Community video? What do you mean?

Well, we had this video group, a collective, we were nine, called it ‘Video Nou’ [lit. Video Nine] that was alternative too.

For several years we filmed in a neighborhood named Canserra, it was a growing neighborhood, they were constructing many buildings, the subway.

It was working class people, and had a school for adults. We filmed the filmed the school for adults, interacted with them, maybe spent two months working with the school, teaching. We went to the market and put the television and showed them what we had filmed just beside.

Then we also did the ‘ateneus’, it was a time where a lot of people’s ‘ateneus’ appeared, there still are some. That’s that somewhat alternative youths got together and were called ‘ateneus’. We filmed it, allowed them to speak, and then showed them what we had done. Then you got the feedback so that people spoke more about it.

We filmed all the demonstrations, the bicycle demonstration that there was, the gas stops strike, that was tough…

Well, it was community video working with the community. It became fairly in, well, there were books more a fashion, in California, where the hippy movement happened, the alternative movement. We filmed a lot on the streets. There weren’t many televisions, they were owned by the government. So it was great to film the common people, with a topic, and then show them, put it on a screen or a bar and let them see it.

Did your art have any repercussion due to Franco’s death?

Art, here in Barcelona and Spain… Well, art was quite forbidden. Artists, in a generation, went to Paris, France. Then they started toing to New York, I have many friends that went to New York. I should have gone and didn’t go. But the artistic movement in that moment, the 70s, was in New York.

Here between that there weren’t many galleries, there weren’t museums and there weren’t many galleries there was little to be done.

Apparently an alternative art appeared, conceptual art that at the beginning was like forbidden. But like I said, before Franco died everything started to get open. Of course, when Franco died you could do what you wanted: graffiti on the streets, happenings, galleries sprouted like mushrooms.

I was a photographer in a gallery, ‘Galleria G’, that lasted some years. They exhibited Warhol’s serigraphs, conceptual and I was a photographer there.

When this one was over, they opened a gallery named “Mec-Mec”, that was the alternative to the Maeght gallery. There we made videos. There exhibited for the first time Mariscal, a Valencian artist and designer who has lived in Barcelona all his life. He designed Cobi for the Olympic games.

‘Ocaña’, who was a notorious character that later burnt and died. A very alternative person, he set up the gallery as if it was an Andalusian patio. Mariscal set the whole gallery as if it was a hotel, with the reception and armchairs.

Ocaña set up an Andalusian patio, he even brought his bed. Some day he slept in the gallery, they danced every day, filled it with shapes and… Well, very alternative art, it was great.

Do you think there’s a feeling underneath the artists in Barcelona as a result of the repression of the dictatorship?

In Barcelona, in the 30s and 40s, there were already some very good landscapers, like Mir. But modern art… well, Picasso started here.

‘Les demoiselles d’Avignon’ [lit. the ladies from Avignon] is something that isn’t very clear whether they are whores or a memory. He combined with African images, but it does seem that it was a brothel in the ‘Avinyó’ street.

He lived in the Colon avenue, besides where I’ve lived 24 years. He was young, attended classes there, and from the African art and those whores he made several drafts that ended up being “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”, one of the important works of the modern movement.

Also here we had some surrealists a bit before and then there was Tàpies. Tàpies was around long due to the [materic material].

Who else? We had in the Empordà and Figueres, where they are always a bit crazier, Dalí.

As a great painter from here there’s Miró. Miró started painting quite realist, like Picasso. In the monastery of Montserrat there’s a picture of a dead woman in the wake that he painted when he was seventeen. Everyone is always shocked with the painting, total realism. But that’s when he was seventeen, then he evolved.

Miró went to Paris too, all those went to Paris. Picasso went to Paris, Miró went to Paris, Dalí went to Paris, although he was still in Cadaqués. Between Miró and Picasso they revolutionized painting here.

There was an important event that was the ‘Pavelló de la República’ [lit. Hall of the Reppublic] in the fair of Paris the year 36. Sert, a great Catalan architect, designed the ‘Pavelló de la República’. Picasso painted, for the hall, the Guernica. The Guernica? No. Sert designed the hall, Picasso painted a great painting, Miró a huge fresco that was lost, this guy, what’s his name, that made mobiles [sculptures, not phones], made a mercury fountain that can be found in the Miró foundation. The mercuri because he came from the Almaden mines.

All that was the ‘Pavelló de la República’, but then there was the war here, and it passed a bit to the background all these things.

But it was an important moment. During the republic here, just before the national uprising by Franco, there was a very important movement both on schools and art, a very strong cultural movement.

You’ve mentioned there painters and illustrators, but is there a Catalan painter or illustrator that serves you as inspiration?

Catalan painters are very important already. Painters and photographs, because Català Roca has a picture of an espardenya stomping a swastika, very famous.

Miró made a post stamp during the war to gather money, but I think that was never done. But he painted…

All these during the war were important artists. The thing is that it was a long time ago . I started painting and creating art not too long ago.

I passed by the conceptuals, I was very interested in conceptual art because I had many friends who were. Then the abstract, I’m with abstract now. But to tell the truth, getting influenced now it doesn’t matter if it’s Catalan, American or Chinese. We’ve reached a moment where influence come from everywhere.

I don’t know from who I could draw inspiration.

Anarchism and the symbol of anarchy had, here in Catalonia, bigger importance than anywhere else in the world, because this was the city where anarchism gained more importance. Do you think arts have been affected by that anarchist heritage?

The anarchist movement…

Or in the past, if the anarchist movement had any influence in art.

The anarchist movement in Barcelona was one of the biggest in the world. Maybe its strongest influence in art is that anarchism was freedom and going against the conservatives and the establishment and dictatorships.

Anarchism used to give freedom, and maybe that’s reflected on the arts. Regarding the arts there were also the posters that anarchists did during and before the war. I couldn’t tell you the name of any poster maker now, but there were many important ones. Photographers like Català Roca took a very strong image of anarchism. But it was art more on a street level, rather than pictures to have in dining rooms and museums. It was a more direct image: graffiti, posters, flyers.

Can you talk a bit about the history and impact of anarchism in Barcelona?

I’ve followed anarchism in Barcelona quite closely. I followed it in my time and as a friend of the young anarchists, but of the old ones as well.

Now there’s a friend making a movie about anarchism here in Barcelona. I’ve lent him a lot of footage we filmed. Because we filmed the strike of the gas stops, the ‘Jornades Llibertàries’, the meetings of the CNT, we filmed a lot of history.

Anarchism here in Barcelona was very important to go against a conservative government. But, and I don’t want to overstep here, anarchism and communism fought each other before the war. That degenerated a lot, they fought each other which allowed the right-wing to win and the coup. If they had worked together…

Truth is that the conservatives always groups together and they all go as one and left-wing always fights. This is happeing now, the right-wing, the PP, the old ‘alianza popular’, ’convergencia’, all the fascists go together. And meanwhile ‘Podemos’, the socialist party and all the ones here are going each their own direction. Which deep down is more interesting, to have a criteria, the others go… But it turns out that the right-wing ends up winning.

How did anarchism manifest in the 60s and 70s?

Anarchism in the 60s and 70s was an important movement. There was the cinema syndicate, that was led by Bellmunt, a movie director, Andrés Grima, that organized the ‘Jornades Llibertàries’. There was the transport syndicate, in a flat in Medinaceli square where I lived in half this huge flat they had. There they held the meetings, I filmed the meetings, quite tough. These were the ones that organized the gas stations strike. They had many flats and it was all quite strong.

But like I said before, with the ‘Jornades Llibertàries’ it all ended quite a bit. The young anarchists came, who are not so much about flags, but rather about sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, and the other ones were terrified by that.

Anarchists, for example with love they all have their wife and all. They’re very serious, very…

And then, talking about the culture of the youths in the 70s and 80s, how they were in that time. In the period while Franco lived and after the dictatorship, because I can imagine that on one side it was repression but freeing on the other.

Of course, youths during the 70s… That was really long ago. It was back then that soft drugs came in, like smoking, and the contraceptive pill, that’s very important. It was the 70 or 71, and it freed sex.

When the pill came out, sex was freed. Up until then, everyone was really prude and suddenly, free sex, you made out every night with whoever you could.

There was alcohol, there were drugs, and freedom started, but how can I put it. I remember, as a big thing from back then, when I used to go often to Ibiza and Formentera, that they made the Instant City, a city of inflatable plastic that was done in Ibiza. There was a design congress that was celebrated every two or five years, I can’t recall now, but when it was Spain’s turn they decided to do it in the beach of Sant Miguel, in a huge hotel. There were many Japanese people because the next congress would be in Japan.

Every time one of this design congresses there was something alternative done. Here, between an architect from Madrid, Ferrater in Barcelona and Jordi Serrat, they decided to do a city of inflatable plastic. Aiscondel gave the plastic away, and I could tell thousands of anecdotes about that. They set up two fans to inflate the city, there was the beach Sant Miguel by the hotel and down the plain this inflatable plastic city, all very hippy.

At first it was great until hordes of people arrived and it got out of hand. But you got there, cut your plastic with some casts, fixed it on the earth, made a hole and boom, it inflated and you had your own place.

The design was great there, I saw the first video system, from some Americans who arrived with it. That was the 71.

The youth… The ones that were involved were few, I have to say. We frequented Ibiza and the first years of Formentera. The first clubs started, the Bocaccio, the Gauche Divine and all that.

There were clubs in the neighborhoods u bit was more during the day. Clubs with more modern music, that started to come in from England specially, and they started to open bars, and locals and…

Until then there was a maybe more alternative story that were the ateneus, more politized, more in the neighbourhood. But in the center of Barcelona the bars, galleries and concerts started.

Gay Mercader, Pino Sangliocco started organizing music festivals like the Tangerine Dream. It started in Granollers, where there was a colours performance by Dalí, there was a concert by Tangerine Dream or King Crimson, that must have been around the year 73.

The concerts of modern music where we all met and well it was this… There was an evolution. We came from Woodstock, the festival on the Isle of Wight, to which I didn’t go but had to go. Here started the Canet Rock, that started the 75. Maybe the festival of Canet was even before Franco died, the first edition.

And well, festivals started and freedom really. It’s important the pill and the sex. Drugs and weed were a bit freedom as well, but…

Specially the entrance of movies and books that didn’t make it in during the times of Franco. It was a breeze of free air, free air from the outside came in.

This blow up city did you build your place in the water?

I’ll show you images about it, it was a weird story.

I found about this later, when I had a wife with whom I had a child. Her father was who donated all the plastic.

You did like a sort of dome, it went out a bit, there you stuck another bit of dome and it was inflated by air. Instant city.

What was Bocaccio? We read that it existed from the 67 to the 85, who created it? What made it special? What kind of people went there?

The Bocaccio here in Barcelona… There were small clubs in neighborhoods, but not this big club for bourgeoisie or progresist people. Then Oriol Regas, a great person, created the Bocaccio.

Oriol Regas is a great person who before the Bocaccio had already crossed with some Friends and some Montesa motorbikes I think, I don’t want to get it wrong, crossed all Africa. Then they came from Japan or India with a boat made of hemp, he was quite the adventurer. He was a rather shy guy that always hid his face. He was shy but really nice, he was a huge friend of mine, Oriol.

Then Oriol and his brother, Xavier Regas, who was a decorator a bit like that, created the Bocaccio.

For starters the decoration was already wooden, with red towelling, all very though through. There was an upper story and a lower one.

Oriol, who was with the Gauche, had a home at Empordà and was a friend of all the intellectual and left-wing people, managed to gather on the upper story all the intellectuals of that time. Many architects, like Tusquets or Bofill, many cinema directors, many philosophers, many writers. They all met upstairs, smoked their cigars, drank their whiskeys. Herralde, from Anagrama editorial. Well, they gathered upstairs and talked, organized, flirted, exchanged couples, their women, organized a lot of work. Those people worked a lot back then. By night they were on their cups and by day they worked.

I was a bit younger than those ones. I used to go to the Bocaccio and a friend of Oriol. I went to the lower floor, there was some really good music, Carlos Carreras, I can’t remember now, downstairs you danced and made out and upstairs were those.

It was such a thing that people upstairs was… what’s his name, Joan Segarra, who used to go a lot, in an article called them the Gauche Divine, the divine left. The Gauche Divine because they were all left-winged but were all divine. They were all simpatizers of the communist party but didn’t focus on that. But very left-winged.

Many of these were in the ‘caputxinada’, where in there and then taken. There were also singers, like Serrat, who else… Well, it was the Gauche Divine.

There was a woman, Teresa Gimpera, who was a bit their myth. There were more women… damn, one that owned an publishing company and was a writer. There were men and women there, it was very up to date. They all gathered in Bocaccio, were called the Gauche Divine, they were talked about a lot.

Oriol Regas had a magazine, every year they went to Rome or New York. On the first trip to New York they all arrived completely drunk, the captain ended up having to tie them up. He created a magazine, set up a radio program, organized concerts, the first concerts of music a bit alternative were set up by Oriol Regas in a place called Price,

He was a great carácter. The Bocaccio ended up disappearing and then he set up the Up&Down, that can be considered the same but a bit more posh. Upstairs, to the Up went the posh people, that weren’t so much intellectuals now, and Down went the sons. I must say that I’ve gone to both, because I have been setting up clubs and things. But it was a strong movement, the Gauche Divine was an important movement in Barcelona.

If you could go back to one of those nights, what would you see?

In a night of going out to the Bocaccio the first thing you’d meet would be the three doormen, all wearing tuxedo; the waiters wore tuxedo as well, all very polite and served perfectly. The doormen filtered many people out, but if you were a friend or from the group, they wouldn’t tell you anything.

I had been in the India and came dressed up as an indian t osee if they’d let me go in. I wasn’t sure, the others were all wearing tie.

And upstairs you found these. Herralde, Joan de Segarra discussing with Tusquests, Serrat, well, all of these talking. They didn’t go downstairs often, there they were younger and more dancing.

And downstairs… You could also flirt, there was some alone babe, it wasn’t the time… Then I set up a club named Bikini where the women would usually go alone, which doesn’t happen now. Some went alone to Bocaccio, or they were friends or acquaintances. The music was great, from England. All in all, a great place.

It was a great left-wing and alternative place. Left-wing, but like I said, Gauche Divine.

The second question was about the Gauche Divine.

The Gauche Divine was this movement that came out of the Bocaccio. Well, it was created in the Bocaccio. There were many writers, Joan de Segarra, journal writers, novel writers, Vázquez Montalban, architects, philosophers, publicity people, models. The most top model of that time was Gimpera. She was a woman that took her children but chose her, made a few commercials, made movies.

And well, the Gauche Divine was a left-wing movement. Something that now… I haven’t always missed it. It’s received many criticisme the Gauche, precisely for being Divine. They were Divine because they had Money, but they weren’t daddy’s sons, they had Money because they worked. Writers wrote books, architects built buildings. They had Money, went out, had fun and all that. They were left-winged but didn’t belong to the communist pary, they were simpatizers, yes, but didn’t belong to communist or anarchist parties, didn’t have a tag. They were just left-winged.

What was the Bikini club bakc then, who managed it, and if you have ant stories.

My story, that I’ve told you I’m writing a book with a friend with whom I managed the Bikini club. We started with another club called ‘La Seca’ [lit. the dry one] where now there’s a theatre. ‘La Seca’ used to be the ‘Casa de la Moneda’ [lit. house of the Coin, royal mint] and there we set up a club that was like a marquee.

It lasted less than a year because the Street was very narrow, the neighbors moved against it. Quique, set everything up with me, it was his project and I joined, he was thrown out in two months and I left with him. We were there two months, but it was a wonderful place.

Afterwards Quique managed other clubs and I always collaborated. Then he set up a movement that was named Turmix, turmix is the blender. Every Thursday it was a different place. Journalists called it the nomadic rhythm.

Every Thursday we brought people to a club in Barcelona. We passed through 24 clubs.

You have to consider that those were other times, and communication was made by post.

festivals i la llibertat

The doormen they had, half were shocked. Then we passed through Bikini, where I had already gone with a party of the FAD, a local design organization.

We passed through Bikini, passed again and stayed there. We passed thorugh one called Orfeo, passed again and stayed there too. In Orfeo we set up the after hours, the first one in Barcelona.

I had been in New York, in New York the called after hours those that open at six in the morning. Here we registered the name, it was mine for ten years, and opened daily from six to nine.

But Bikini was a fantastic club set up by a Belgian man the year 53. He called it Bikini because the French had thrown, the Americans started the nuclear trials, the French threw a bomb on the Bikini atoll in the Pacific. An atoll that a year ago the ONU declared it World Heritage Site. But it was a coral atoll and threw the first atomic bomb.

When this Belgian man set up Bikini he said, “this will be the bomb” and named it Bikini.

Another French man, the year before, designed the bikini swimsuit for women, and also said it would be a bomb and named it bikini too, they are coincidental.

Then Bikini was a club the year 53 with two vibes, we created even another one on the outside. There was a rock area, one of salsa, salsa started in Barcelona in Bikini, we started it. And since this man in the year 53 had done everything, we were also allowed to do everything.

We did the Wednesdays’n’roll, with rock concerts; the Thursdays ‘Dishows’, where we showed from weird movies to weirder strip-tease shows; the ‘martes artes’, we showed movies from cinema directors, we did things.

We lasted for about five years in Bikini. At the beginning, it was hard because they opened one, Otto Zutz. A friend of mine who had been in Turmix, but with a group from EINA, set up Otto Zutz. They had a bit…

And bikini was a very open place. Well, it was a club with a mini-golf. It was the ground floor. The minigolf was always the owner’s, but we could manage all the other parts.

Women always told me that they went to Bikini alone. They came out from work and went to Bikini. All the journalists, writers, musicians went there. It was a great place. I closed the 90 with a party that everyone remembers, the minigolf was razed, everything was razed. For me it was a fantastic time as well.

There are many anecdotes from the Bikini club. Maybe an important one is that the cheese and ham sandwitch, the ‘caliente con jamón y queso’ [lit. hot one with ham and cheese] as it’s known in all Spain. The man who set up Bikini was Belgian and gave crocque-monsieurs, that he did with two slices of bread, there are some that have only bread, cheese and ham, but he made it double.

Then people from Barcelona, when they went somewhere else said “I want a sandwich like that from Bikini”. And here in Barcelona the sandwich of ham and cheese started to be known as Bikini. In Catalonia, it has extended and in Spain there are certain places that if you order it like that they know what it is. The name comes from Bikini, the club.

Are there any other clubs and bars that were important during the 70s and 80s.

Barcelona, the 70s and 80s. It was widely known in the 80s for its designer places. It was because, I was discussing it with some friends the other day, I suppose there was an economic euphoria, there was money.

There was a crisis in the 90s that we didn’t notice here because we had the Olympic games, I’ll talk about this later. But there was money. Also there was a whole promotion of young architects from the architecture school.

When I studied architecture the architecture school was quite strict. There were quite good architects, Sert, Moneo, but they were outside.

There were some young architects and designers, there were very good design schools like EINA, Elisava, and places started to be made. Maybe it started with Metropol, that had neon lights but was quite cold. The Network, where in every table there was a television with all the wires outside that you could see the entrance, with a world globe that went up and down through a hole.

But specially there were decorators, Alfred Arribas, who is an architect, and the other one I can’t remember. Then there’s Dani Freixes. Some awesome bars started to be made.

There was the Nick Havanna, a bar with cow skin, a pendulum from… one that designs lamps, a dome, a black leather sofa, people went there.

But what was very important in these bars were the bathrooms as well. You went specially to men’s bathrooms. The women’s not as much because each had their stall. But in men’s the place to pee were some waterfalls made of stainless steel or irons or something, with stroboscopic lights that you saw the pee like that and water falling everywhere. The first thing you had to do when going to one of those bars was going to the bathrooms.

There was the Nick Havanna, the Velvet. As a club there was the Otto Zutz. Ottoz Zutz is still working, it’s beautiful. From Dani Freixes there was the Self and the Zsa-Zsa.

The designers were great, the designs of the graphisms. They were Peret, America Sanchez, Alfonso Sostres, Isabel Nuñez, well, Patri Nuñez was the graphist, Isabel Nuñez was a decorater with Antxón, the Zig Zag, one of the landmarks was the Zig Zag, that’s the one that later set up the Otto Zutz.

In that time, since I went out a lot at night and had all my places, there was people who asked me out to see places. Then we’d take a car and we’d go, and I’d take them bam, bam, bam, a cup.

It was people who didn’t go out often. They all wanted to arrive to Otto Zutz, but I said to them, “But Otto Zutz doesn’t start until three am” and they didn’t believe it. Back then first you went to have dinner, then to a bar, then to another one. And always, at half past one they started to get nervous, “We have to go to the Otto Zutz”.

You ended up taking them at 2 at Otto Zutz and they said “but there’s nobody here” it was all empty. And I’d say “nobody comes until three” “what do you mean they don’t arrive until three?”

Then we’d have a drink and around two and a half started to leave and someone would arrive. “Well, let’s wait a bit more” and at three, boom, it started to fill up, until six in the morning.

Then I had my afterhours time, that we opened from six to nine.

There was also some restaurant. Correa and Milà, Federico Correa and Alfonso Milà, architects, set up the Flash Flash, that is still open. The Flash Flash was all white, with white sofas and on the walls some pictures of Romy, a model, with a photographer’s flash that are the lights of the place. It’s fifty years old now.

Then they opened the Giardinetto in front. It was the time of the designer places, now I can’t quite remember any more but I could tell you all.

Were drugs common back then?

Back then in clubs you could smoke, well, in clubs and everywhere else. There was as well that you could smoke in the plane, you went to the plane and were allowed to smoke.

In clubs, you could smoke. Drugs and weed, maybe this is the time they started. Cocaine started too, and amphetamine a bit too.

Now that I think of it, in Otto Zutz there were the bathroom, that were a big room with toilets, they were mixed. It was full of stalls where the toilets were. They had to put a doorman in bathroom because four would go into a stall, and when four came in they were kicked out quick. They had to put a doorman to check that people didn’t get high.

And cocaine, yes, they used a lot of it. Like now they use ecstasy and so and methamphetamine, maybe back then it was the time of the cocaine.

It was also the time when heroin got in here, but these people were not so much club goers. It started to get on vogue among working class people that would inject. It also got popular with top people, designers and so. I have a book of Barcelonese counterculture poets that almost all of them died injecting.

Cocaine is still around in Ibiza and those place, of course. It was a time of euphoria, money, cocaine, sex; well, sex, drugs and rock’n’roll.

What was Ajoblanco and what was its message? What was your relationship with that magazine?

In this time appeared the alternative magazines. Cartoon ones, appeared the Star from Juan José Fernandez; the ‘Vibraciones’ [lit. vibrations], by José María Berenguer. Star was great, it had articles and cartoons. Then there was the Ajoblanco too. There was the ‘Vibraciones’, no, what’s the name… Well, Ajoblanco was more of articles in depth and every edition was a bit special.

Alternative energies, sex, drugs, alternative architecture. With long and quality articles. They distributed it great, it was made by Pepe Ribas, Fernando Mir, and another one, whose name I can’t recall.

It lasted for ten years I think aroundseven years and stopped. Later Pepe Ribas tried to get it going again, he started it again and it also stopped because it didn’t work. But now it’s about to come out again.

They’ve done one of those things that they ask money over the internet and so, it’s all working now, they have an office and soon Ajoblanco should be released again. They talked a lot, moved a lot. Pepe Ribas is always out and about, Fernando Mir had retired, and the other one, what was his name? Well, a magazine that was very alternative and very…

It’s quite good, going back to the Gauche Divine. The Gauche Divine was a divine left-wing, and the Ajoblanco is also left-winged, but an alternative left-wing. Without being communist, maybe anarchist, it’s anarchist, about freedom and fighting the establishment.

Can you talk about the groups that were around Ajoblanco?

Ajoblanco, Pepe Ribas when we studied, he’s my own age, many were with ‘Bandera Roja’ [lit. Red Flag], the PC, the communist party. That was before Franco’s death, but it was the left-wing in university. There was also the left-wing in the factories.

Pepe Ribas was very left-winged, commited with ‘Bandera Roja’, and Antxón too. And from here came these movements. I think that after the ‘Jornades Llibertàries’ and after [unhearable] it became a pure left-wing, a bit like ‘Podemos’.

‘Podemos’ is the movement that is there now, it’s not communist. There’s right-wing people who always attacks them as communists, but it’s not communism, it’s young people, different, I don’t know how to define them.

I vote for ‘Podemos’. I’ve voted all my life the socialist party, but the socialist party has been going down lately, making pacts with the money and the government. When money came into politics, and that was a few years ago, it messed up everything. But now there are alternative movements like ‘Podemos’ and so that what they want is the sharing of capital and not that a few keep it.

Who is Pepe Ribas?

Pepe Ribas is quite a friend. He is one of the founders of Ajoblanco, was a close friend of Lluïsa Ortínez, who was in my video group. He has a house in Menorca, I’ve been in Menorca for a long time, I have sister who lives in Menorca.

He comes from this movements, the ‘Bandera Roja’, the communist party, from when he was studying. I think he studied, I don’t know if it was economy, now I can’t remember what Pepe Ribas studied.

And they started that movement. He now lives in Empordà, near Jordi Esteve and Luis Racionero. Luis Racionero is a man, a writer, maybe a bit older than we are, but he was very influential, he was there at the beginning of Ajoblanco. He comes from the alternative movements in Berkeley, the counterculture that started in Berkeley. He was very involved in all the movements and then here, he has written many books and then was among the founders of Ajoblanco too. They are the counterculture, I’d say.

How did you take part of the Ajoblanco movement?

In that time, the 70s and 80s, I always say that we must have been few people, because we all knew each other. Here in Barcelona everyone knows each other, but that was… If there was a concert, you went there, if there was a magazine…

I specially did photography, I published photographies in Ajoblanco. We lived in [too fast], we had a very big flat when I did video, we were the whole video team, nine, and there was always more people in my home. But at [too fast again] I was with the ‘Energias Alternativas’ [lit. Alternative Energies]people, they had the ‘Alfalfa’ magazine and another one the name of which I can’t remember, we were all day together.

And of course, Pepe Ribas and all those spent all day there. And since it was a big house, we hosted a lot of parties, so everyone came to the party.

The Pepe Ribas, between the video I did, which was the most alternative thing in that time, and the ‘Energies Alternatives’ that did Manel. As an architect I also did things with them, ecological houses with solar panels and that, I was involved with everything, and Ajoblanco was interested.

I think that we weren’t many, and those involved in everything even less. There have always been people who didn’t find out about anything, but if you wanted to you could find out.

Which do you think that were and will be the goals of Ajoblanco?

The goals of Ajoblanco… I’m not very rethorical and don’t waffle on much. The goal is to show alternative topics to the way society is set up now. For example, the alternative energies that I mentioned. Up until recently, there was a minister, who is now out of office, that put taxes on companies that built solar panels and alternative energies.

Ajoblanco takes the alternative energies instead of the plug in energy and big electric corporations. The big electric corporations is where the corruption is. All the politicians end up in electrical corporations with fantastic salaries.

Then also showing other politics than the ones that are now in place. Ajoblanco would be, I suppose it is, simpatizer of ‘Podemos’ too. ‘Podemos’ is a movement that comes from the 15M. Suddenly the young people rebelled, camped in ‘Catalunya’ square here, in the ‘Plaza del Sol’ [lit. square of the sun] in Madrid, and from there came the 15M.

Regarding sex, they also are against marriage, finding a woman, binding to her and being together for life. The convservatives have that and their lovers, but that’s secret.

Ajoblanco and the alternative movements made love with who they could, if the other wants too, without raping anyone.

And in politics, well, and economy too, a sharing more… Right now, in the world there are rich people again, the richer ones are now and people without money is poorer everytime. But there’s lots of money. In Africa there’s people starving to death, so how can you collaborate with ONGs, Ajoblanco is a lot of collaboring with ONGs. With migration, poor people, we bomb their country, kill everything and then don’t let them here.

STAR was another magazine, can you tell me about it?

Before, when I mentioned ‘Vibraciones’ there was another one, ‘Víbora’ [lit. Viper]. ‘Vibraciones was a magazine a bit like Ajoblanco, many alternative magazines came out at that time. Of music, ‘Popular Uno’ [lit. Popular One], and the ‘Vibraciones’ was about music and alternative topics like Ajoblanco.

Then came the STAR, maybe it even came before. STAR was created by Juan José Fernandez. There were comics, but more harsh, more alternative, and great articles from Pau Maragall, who signed as Malvido, from Jope María Martí. As I said before we were a small group, Pau Maragall filmed with me, he was the brother of Pascual Maragall, the great mayor of Barcelona. And with Josep María Martí we’re friends since we were kids. I’m the godfather of his son and we have a house in the [river Ebro] delta, quite close.

Well, all this people wrote about alternative movements, it was going against the established power that is what’s needed now, because everything is like shit.

The problem with the world, between Trump winning in the United States that is already economy over everything, total madness, the money, and I don’t know how it will end.

But now I think it’s quite well with the one who won in France, the ultra right almost won. With the one who won here in the socialist party, Pedro Sanchez, instead of the established socialists. I think now is coming out a strong movement.

Was ‘Nueva Lente’ [lit. New Lense] another magazine?

In that time, besides magazines with alternative articles and comics, there appeared really good magazines of architecture and magazines of photography. Here in Barcelona appeared the ‘Papel Especial’ [lit. special paper], I don’t remember which others.

There was a gallery in Balmes street, that later in Aurora street set up a whole building as a gallery. And in Madrid appeared ‘Nueva Lente’. In ‘Nueva lente’ there were some really alternative pictures. We were still used to pictures of landscapes and potraits, in ‘Nueva Lente’ there were photos of part of a shoe.

Garcia-Alix I suppose published ‘Nueva Lente’, I have many friends here. I loved ‘Nueva Lente’. It was another way to see photography, to see the world, and these articles that were aobut this photography also dealt with another way to see the world: without clichés and a bit the way you wanted.

In this time I can also say that started to come out the cinema of Pedro Almodóvar, for example. He was a huge friend of mine, when he came to Barcelona he came to my place. In that time he worked at the post office and filmed silent movies with super 8.

Then, when he showed them, he showed them in the fotography center, the cinematheque, Magic, that was a club; he showed them, took the microphone and he voiced those short movies. We got high a lot, I have to say, with weed and alcohol and had a lot of fun, but he didn’t come often.

Once we even dressed him up as an advertisement man. We took them around Rambles, it said ‘Pedro Almodóvar presents his movies in Magic’, we went by the Cathedral, the Town Hall, and by night few people came to the movies, but well.

Then I introduced him, he had already filmed half a film with 16 milmetres, ‘Pepi, Luci, Bom y otras chicas del montón’ [translated as Pepi, Luci, Bom and other girls like your mom], with all the ‘movida madrileña’ [lit. Madrid’s movement], Alaska, all the people form Madrid, he did it in 16 milimeters.

Those movies with super 8 were also being filmed by all that Madrid people, that then was the ‘movida madrileña’, those are still around.